ARTICLE AD

When night fell on Uganda’s second-largest national park in early February, Jacob, a three-legged African lion, made several attempts to cross a dangerous channel with his brother, Tibu.

Automation Never Tasted So Good

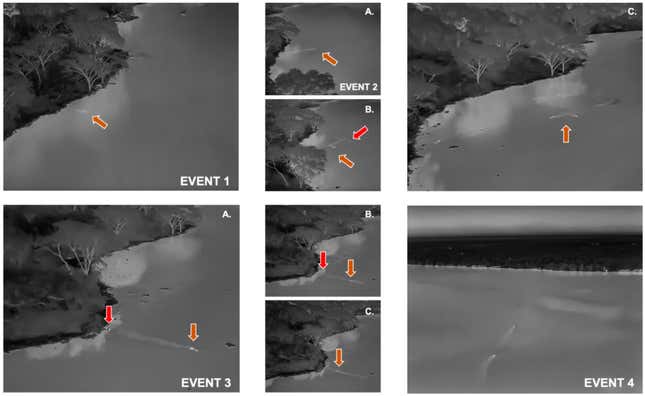

Likely motivated by a scarcity of lionesses and the “strong” presence of humans at the only available land connection, the two lions repeatedly entered the Kazinga channel in darkness. They doubled back three times, “due to what appears to be encounters with either hippopotamus or Nile crocodiles,” researchers wrote in an upcoming paper accepted in the scientific journal Ecology and Evolution.

On their fourth try, the siblings successfully swam as far as 1.5 killometers, or 0.93 miles, to reach the other side, in what researchers called the “first visually long distance swimming event recorded for the species.”

Gif: Luke Ochse

Jacob completed the crossing in spite of losing his foot in a poacher’s trap, per the paper. Researchers filmed the journey just after 10 PM local time, using a H20T thermal camera and a DJI Matrice 300 drone, while keeping a distance of 50-70 meters, or around 200 feet.

Griffith University scientist Alexander Braczkowski led the expedition in Uganda’s Queen Elizabeth National Park, with funding from Queensland, Australia’s Griffith University and Northern Arizona University. “It was pretty dramatic,” Braczkowski told the New York Times. The lions look “like two tiny little heat signatures crossing an ocean,” he said, remarking on footage captured by Cape Town videographer Luke Ochse.

Image: Dr. Alex Braczkowski

Humans have documented African lions on shorter aquatic journeys, usually no farther than 100 meters, or around 0.06 miles, according to the paper. Members of the vulnerable species aren’t known to be big on swimming. Jaguars, on the other hand, are “well known for their swimming ability in wetlands like the Pantanal and in floodplain forests in Brazil,” the researches noted.

Beyond Jacob’s and Tibu’s quests for sex and territory, the swim reflects how the planet’s “most imperiled and iconic wildlife are facing tough decisions under increasing human pressure,” the researchers said. “Swimming across rivers and water bodies filled with high densities of predators is one such example.” The researchers concluded the paper with a call for more research into the connection between long swims and the functional habitats of big cats in areas increasingly dominated by humans.

5 months ago

35

5 months ago

35