ARTICLE AD

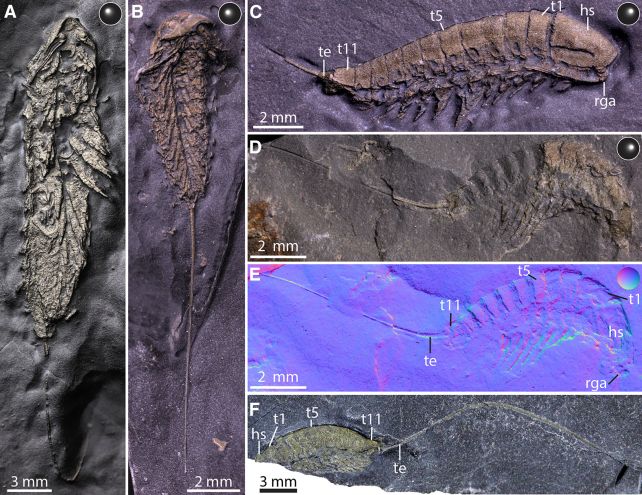

The holohype fossil of the new species, Lomankus edgecombei. (Luke Parry)

The holohype fossil of the new species, Lomankus edgecombei. (Luke Parry)

Most of the fossils that we find in Earth's crust are preserved in sedimentary rock, where layers of mineral cover an organism and, over eons, harden into stone, dead beastie impression and all.

But the stunning golden fossils discovered recently in New York State are a little different. Their tiny bodies had been slowly replaced by a metal known as iron pyrite, or fool's gold, ensuring their shapes remained in exquisite condition for 450 million years.

"As well as having their beautiful and striking golden color, these fossils are spectacularly preserved," says paleobiologist Luke Parry of the University of Oxford in the UK. "They look as if they could just get up and scuttle away."

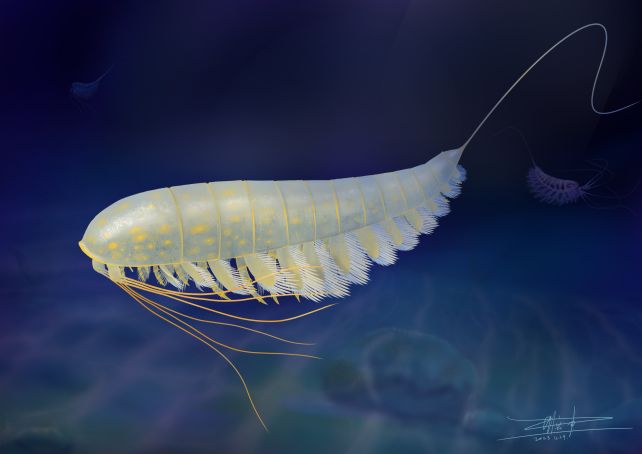

Named Lomankus edgecombei, the species represents an entirely new marine animal belonging to the Megacheirans — an extinct class of arthropod with large grabby arms at the front of their bodies for capturing their prey.

An artistic reconstruction of L. edgecombei. (Xiaodong Wang)

An artistic reconstruction of L. edgecombei. (Xiaodong Wang)Fossilization can be pretty rough on the original material. Processes often subject the remains to pressure, heat, or a combination of both, resulting in significant alteration of the anatomy that makes it difficult to see its features clearly, or in three dimensions.

A fossil bed that preserves organisms in exquisitely fine detail is known as a Lagerstätte – and a Lagerstätte known as Beecher's Trilobite Bed is exceptional even among this class. Although it's just a few centimeters thick, it contains the fossils of a number of ancient trilobites whose bodies have turned to fool's gold.

This is where Parry and his colleagues found L.edgecombei.

"Pyrite forms today through the action of sulfate-reducing bacteria that break down organic material in the absence of oxygen and produce hydrogen sulfide," Parry told ScienceAlert.

"This can then react with iron to form pyrite, which is iron sulfide. So, to form pyrite you need organic material, iron, and a lack of oxygen. The sediments that contain the fossils are low in organic material but high in iron and so the carcasses of the animals preserved there are like small islands where the conditions for pyrite to form are just right."

Some of the tiny fossils emerging goldenly from the Lagerstätte sediment. (Parry et al., Curr. Biol., 2024)

Some of the tiny fossils emerging goldenly from the Lagerstätte sediment. (Parry et al., Curr. Biol., 2024)The animals were likely buried alive in huge dumps of sediment carried by events called turbidity currents, creating a very special set of conditions that allowed the arthropods to be pyritized from the outside in.

The result is a set of L. edgecombei fossils that are exceptionally well preserved in three dimensions, giving us new insight into the anatomy of Megacheirans. And these little guys are particularly exciting, because they lived in a time when the Megacheirans were on the decline. This class of critters was abundant and diverse during the Cambrian, between 541 and 485 million years ago, but were mostly extinct by the early Ordovician period that followed, between 485 and 443 million years ago.

This means L. edgecombei was one of the last surviving Megacheiran species on Earth, and its anatomy offers some insights into how the appendages on the heads of arthropods changed into the antennae, pincers, and fangs seen on insects, crustaceans, and arachnids today.

"Today, there are more species of arthropod than any other group of animals on Earth," Parry says. "Part of the key to this success is their highly adaptable head and its appendages, that have adapted to various challenges like a biological Swiss army knife."

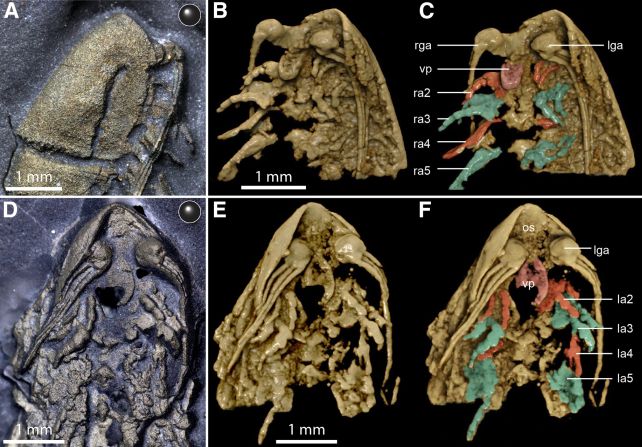

The anatomy of L. edgecombei's head, revealed by micro-computed tomography. (Parry et al., Curr. Biol., 2024)

The anatomy of L. edgecombei's head, revealed by micro-computed tomography. (Parry et al., Curr. Biol., 2024)The fossils reveal that the grabby arms seen on other Megacheirans, known as 'great appendages', shrank and changed shape for L. edgecombei, suggesting a change in function. The claw used for grabbing in other species is much smaller; meanwhile, three long, whip-like appendages known as flagellae are much longer.

Since L. edgecombei had no eyes, this change suggests that the creatures used their great appendages for sensing more than prey-snatching.

"Rather than representing a 'dead end'," Parry explained, "Lomankus shows us that megacheirans continued to diversify and evolve long after the Cambrian, with the formerly fearsome great appendage now performing a totally different function."

The research has been published in Current Biology.

3 weeks ago

43

3 weeks ago

43