ARTICLE AD

Antarctic fur seal and king penguin. (Paul A. Souders/Getty Images)

Antarctic fur seal and king penguin. (Paul A. Souders/Getty Images)

A deadly animal pandemic is on the brink of going global.

Scientists have officially documented highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) in several species of bird and mammal in the most remote region of our planet, the Antarctic – an icy refuge never before beset by such a deadly strain.

Since 2021, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b has decimated wild bird and mammal populations worldwide, rapidly spreading out of Europe to North America and on down to South America.

Genetic assessment of the virus suggests it is now starting to leak into the Antarctic region, probably carried southwards by migrating birds.

Scientists have long feared this moment would come. Iconic species in the region, like albatrosses and penguins, are facing an existential crisis.

"Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic islands possess unique ecosystems which support the population strongholds of several avian and marine mammal species," write the authors of the recent paper, which is based on data from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"High mortality disease outbreaks therefore represent a substantial threat to already vulnerable seabird populations."

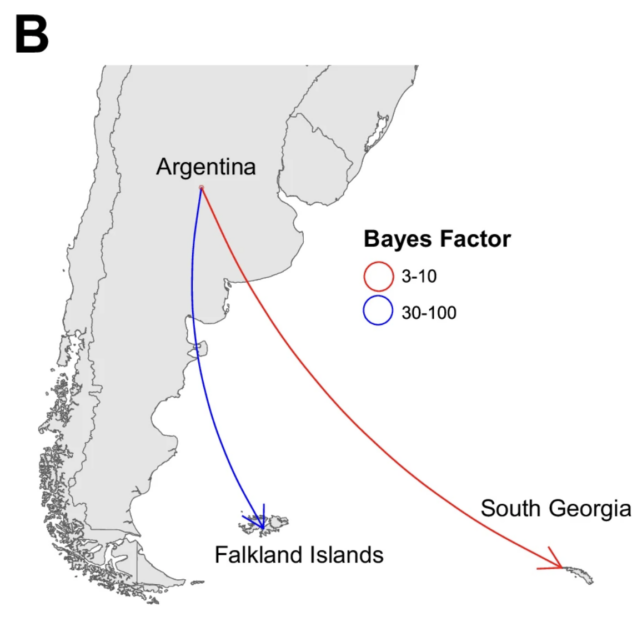

H5N1 HPAIV transmission from the South American continent to the Falkland Islands and South Georgia. (Banyard et al., Nature, 2024)

H5N1 HPAIV transmission from the South American continent to the Falkland Islands and South Georgia. (Banyard et al., Nature, 2024)It all started on 17 September 2023, when BAS researchers working in the South Georgia Islands, about halfway between Argentina and Antarctica, noticed a giant petrel twitching and struggling to move about.

When the bird died, brown skuas ate its corpse. On October 8, they, too, started to twitch. Two days later, researchers logged the highest number of bird mortalities ever recorded among non-breeding birds on the islands.

By early December, colonies of southern elephant seals and Antarctic fur seals were caught coughing and struggling to breathe, taking short and sharp intakes.

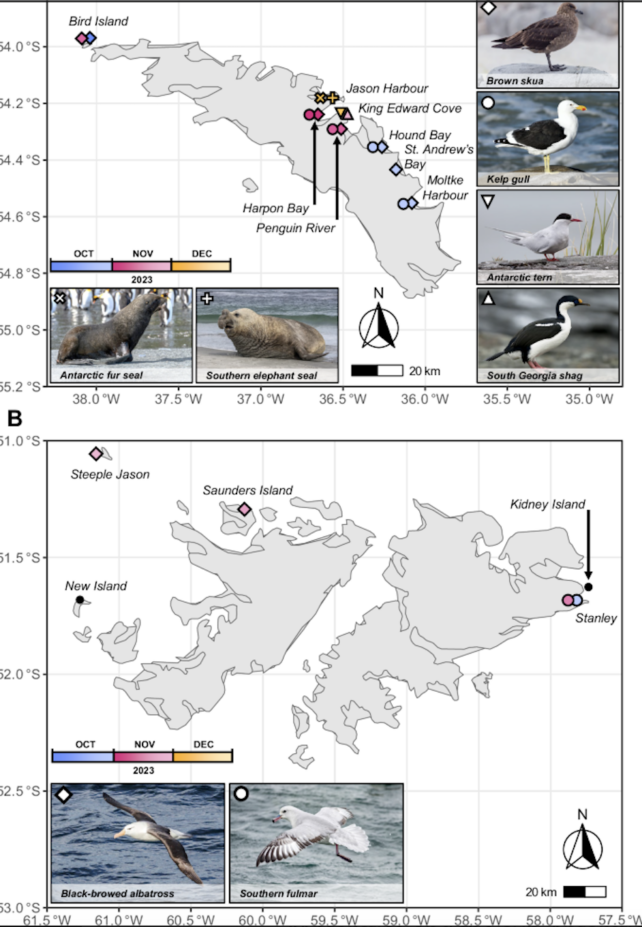

From October 8 to December 9, researchers tallied a total of 33 avian carcasses and 17 mammalian carcasses at eight different locations around the South Georgia Islands. Roughly 66 percent tested positive for HPAIV H5N1.

On the nearby Falkland Islands, which sit closer to Argentina in the subantarctic region, two other bird species tested positive for the virus, including black-browed albatrosses and southern fulmars.

Geographical distribution of H5N1 HPAIV detections from South Georgia and the Falkland Islands. (Banyard et al., Nature, 2024)

Geographical distribution of H5N1 HPAIV detections from South Georgia and the Falkland Islands. (Banyard et al., Nature, 2024)The virus has not yet officially made it to the Antarctic mainland, but some researchers working on the west peninsula think the animal pandemic has already arrived on the remote continent.

In March of 2024, a team of international scientists submitted a study, ahead of peer review, about suspected cases of H5N1 in Adélie penguins and Antarctic shags "at the southernmost latitude so far in Antarctica".

Between December 2023 and January 2024, the team detected the virus at two breeding sites on the Antarctic Peninsula and the west Antarctic coast.

If those results are verified, that leaves just Australia as the only continent without this strain of bird flu. The broader region of Oceania is also free of any known spread.

In South America, the ongoing animal pandemic has proved "particularly severe", Banyard and her colleagues explain, causing mass mortality events for both birds and marine mammals.

Unlike other parts of the world, wildlife in South America have not been exposed to a highly pathogenic avian virus in recent history. Their population mortality rates from the infection are as high as 40 percent among some species.

The tragedy underlines the "extensive ecological impact of HPAIV and the ongoing threat it presents to naïve hosts," the authors say.

For some isolated species in the Antarctic, that threat could be a nail in the coffin. Antarctic fur seals on Bird Island are already facing severe population decline, and penguin colonies on the mainland are experiencing catastrophic losses.

The last thing these birds and mammals need is a pandemic knocking at their front door.

The study was published in Nature Communications.

2 months ago

18

2 months ago

18