ARTICLE AD

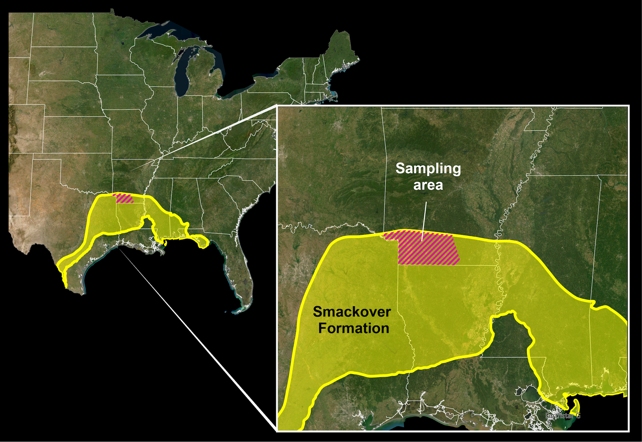

The Smackover Formation, and sampling area in the lower portion of Arkansas (highlighted with red stripes). (USGS/Public Domain)

The Smackover Formation, and sampling area in the lower portion of Arkansas (highlighted with red stripes). (USGS/Public Domain)

Suspended in the relic of an ancient sea beneath southern Arkansas, there may be enough lithium for nine times the expected global demand for the element in car batteries in 2030.

A collaborative national and state government research team trained a machine learning model to predict and map the lithium concentrations of salty water deep within the porous limestone aquifer beneath southern Arkansas, known as the Smackover Formation brines.

The model was trained on existing and new brine lithium data from the region, factoring in known variations in geology, geochemistry, and temperature.

The results suggest there is anywhere from 5.1 to 19 million tons of lithium in the brines, which could account for 35–136 percent of the current estimated lithium resources in the US.

This map of the US shows an inset area displaying highlighted areas for the Smackover Formation and sampling area. The sampling area is located in the lower portion of Arkansas (highlighted with red stripes). (USGS/Public Domain)

This map of the US shows an inset area displaying highlighted areas for the Smackover Formation and sampling area. The sampling area is located in the lower portion of Arkansas (highlighted with red stripes). (USGS/Public Domain)And that could reduce dependence on lithium imports, something US Department of Energy officials have their sights set on.

The study also indicates that in 2022, brines brought to the surface by the oil, gas, and bromine industries contained 5,000 tons of dissolved lithium – a resource that is becoming increasingly critical as we turn away from internal combustion engines driven by fossil fuels, and towards battery-powered electric and hybrid vehicles.

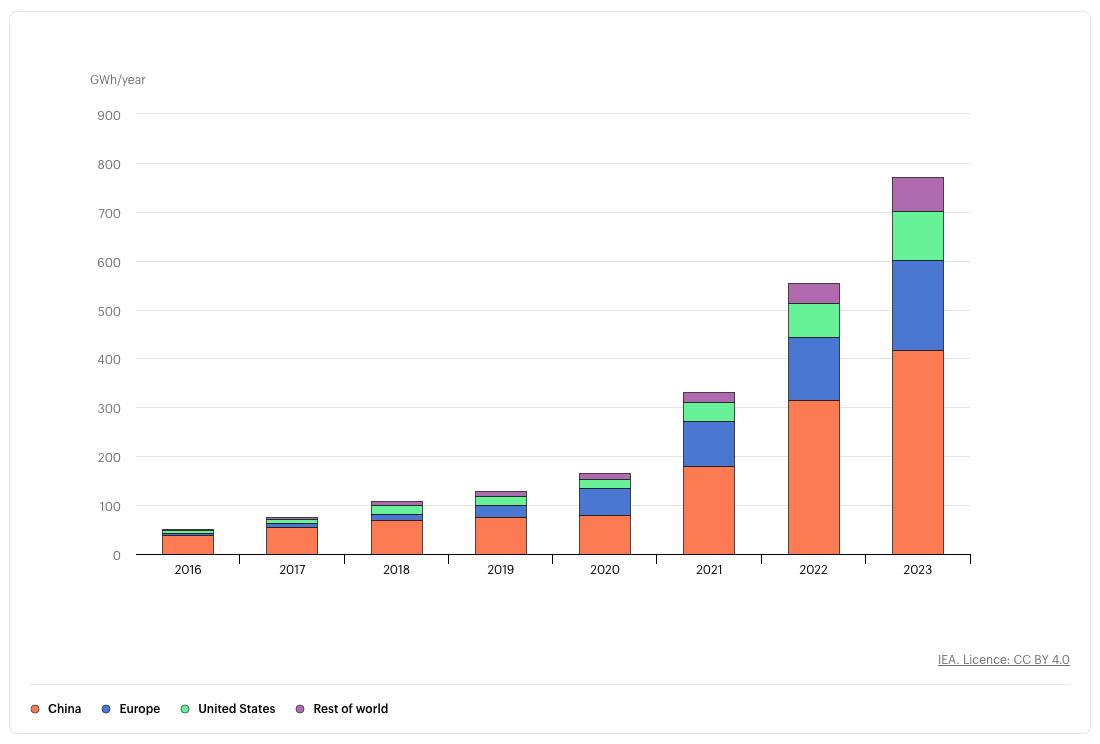

Lithium is the material of choice for electric vehicle batteries, and demand for these is sharply rising. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), electric vehicle batteries accounted for about 85 percent of total lithium demand in 2023, an increase of 30 percent from 2022.

"Mining and refining will need to continue growing quickly to meet future demand," the IEA reports.

Demand for electric vehicle batteries is increasing in all regions worldwide. (International Energy Agency, 2024)

Demand for electric vehicle batteries is increasing in all regions worldwide. (International Energy Agency, 2024)But any mention of new mining and groundwater extraction can and probably should raise an eyebrow.

Other forms of lithium mining involve strip mines – which decimate everything above ground along with the deeper layers, and evaporation ponds – which produce only small amounts of lithium at a cost of enormous amounts of water, along with clouds of toxic dust.

In south Arkansas, on the other hand, the bromine industry already uses a process in which brine is pumped out of the aquifer, bromine is extracted, and then the resulting wastewater is pumped back down.

Lithium is, potentially, just an extra mineral to be salvaged in the process – and the researchers suspect this means lithium resources haven't yet been depleted by existing mining, either.

But this process doesn't guarantee zero environmental impact; rather, it's a major unknown one. And a lot of companies are lining up to drill new wells.

Patrick Donnelly, a conservation biologist and the Great Basin director for the Center of Biological Diversity, told Jack Travis from Ozarks at Large:

"We are in favor of electric vehicles and battery storage as a part of the transition off of fossil fuels… [but] we are sort of actively searching for where is lithium production in the United States that is not going to harm communities and the environment."

"There is no such thing as a free lunch. And there are impacts from [direct lithium extraction]," he says.

No doubt this will be a tricky balance to strike, but this new research could be used to help get it right.

"Lithium is a critical mineral for the energy transition, and the potential for increased US production to replace imports has implications for employment, manufacturing and supply-chain resilience," US Geological Survey director David Applegate says.

"This study illustrates the value of science in addressing economically important issues."

This research was published in Science Advances.

4 weeks ago

40

4 weeks ago

40