ARTICLE AD

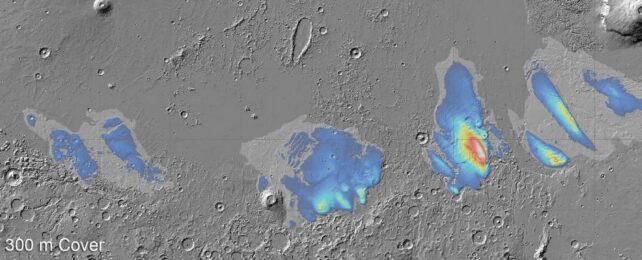

A map showing the potential thickness of water ice buried under the Medusae Fossae Formation. (ESA)

A map showing the potential thickness of water ice buried under the Medusae Fossae Formation. (ESA)

The surface of Mars may appear barren and lifeless, but it seems the red planet is keeping quite a few secrets hidden from prying human eyes.

Luckily, we have technology – and a new radar survey of the Medusae Fossae Formation region on the Martian equator has revealed what appears to be giant layered slabs of buried water ice, several kilometers thick.

It's the most water ever found around Mars' middle, and suggests the dry old dustball isn't quite as devoid of the stuff as we thought.

There's as much water buried there, scientists say, as can be found in Earth's Red Sea; if it were brought to the surface and melted, it would cover Mars in a shallow ocean between 1.5 to 2.7 meters (4.9 to 8.9 feet) deep.

Hints of the buried deposits were first detected in 2007, up to a depth of 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles), but scientists didn't know what they were. New data, and new tools for analyzing that data, have revealed much more about the deposits than expected.

"We've explored the Medusae Fossae Formation again using newer data from Mars Express's MARSIS radar, and found the deposits to be even thicker than we thought: up to 3.7 kilometers (2.3 miles) thick," says geologist Thomas Watters of the Smithsonian Institution.

"Excitingly, the radar signals match what we'd expect to see from layered ice, and are similar to the signals we see from Mars's polar caps, which we know to be very ice rich."

The Medusae Fossae Formation is a collection of huge deposits that extends for some 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles) along the equator of Mars, marking the boundary between the lowlands in the northern hemisphere, and the cratered highlands in the south.

It's not known what created the deposits, but they're huge, standing several kilometers high, sculpted by the wild winds that scour the surface of Mars.

Because the region is so poorly understood, scientists are naturally keen to learn more about it. In 2007, Watters and his team collected radar data that showed the clear presence of something, buried beneath the ground.

What wasn't clear was the nature of that something. Given how dusty the Medusae Fossae Formation is, the deposits could have consisted of buried dust. They could also have been volcanic material, sediment from wetter eons past, or – intriguingly – water ice.

So the researchers collected new radar observations of the region, analyzed the results, and performed modeling to try to figure out what is buried under the windswept dust and stone. And the only thing that fit the data well was water ice.

"Given how deep it is, if the MFF was simply a giant pile of dust, we'd expect it to become compacted under its own weight," says physicist Andrea Cicchetti of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy.

"This would create something far denser than what we actually see with MARSIS. And when we modeled how different ice-free materials would behave, nothing reproduced the properties of the MFF – we need ice."

In the last few decades, as Mars exploration has grown, our previous understanding of the dead dust-ball has changed dramatically. Everywhere we look, Mars shows evidence of water long ago, running over the surface in rivers, or pooling in lakes or oceans.

There's no liquid water on Mars now, that we know of. Where all that water went remains a mystery: did it disappear into space as vapor, or is it sequestered inside the planet, locked away where we can't see it? The Medusae Fossae Formation may hold some answers to this question.

Scientists want to know where to find water on Mars for another, practical reason. When humans are eventually sent to the red planet, they're going to need water for survival. If there's water there already, that will minimize the amount they need to take with them.

Unfortunately, the Medusae Fossae Formation water is off-limits: It's buried beneath several hundred meters of Martian dust, beyond our ability to access.

Still, the discovery raises hopes that there's water hiding elsewhere on Mars. It also gives scientists new information in the hunt to uncover Mars' enigmatic history, and transformation to its present state.

"This latest analysis challenges our understanding of the Medusae Fossae Formation, and raises as many questions as answers," says planetary scientist Colin Wilson of the European Space Agency.

"How long ago did these ice deposits form, and what was Mars like at that time? If confirmed to be water ice, these massive deposits would change our understanding of Mars climate history. Any reservoir of ancient water would be a fascinating target for human or robotic exploration."

The research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.

1 year ago

89

1 year ago

89