ARTICLE AD

Substantial ice loss has been observed in the Antarctic region since the 1970s, but a new study suggests for at least some significant regions it actually started as far back as the 1940s, and perhaps even earlier.

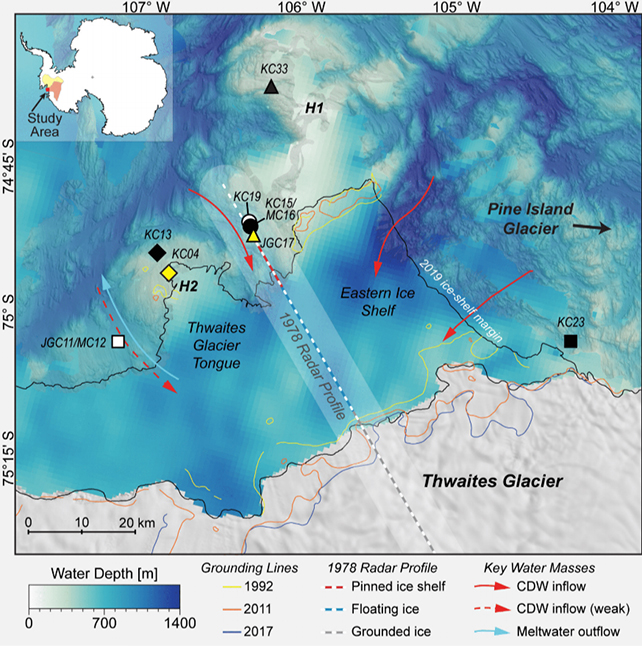

A research team led by the University of Houston collected sedimentary rock cores from seven locations near the massive Thwaites Glacier and nearby Pine Island Glacier to determine precisely when current melting began to ramp up.

Dating back over 10,000 years, the rock samples tell the story of the ice shelves before we had satellites to keep an eye on them and could help confirm estimates on the history of Thwaites Glacier's retreat.

Measuring some 120 kilometers (75 miles) across, this vast river of ice happens to be one of the largest glaciers on Earth. It's sometimes known as the 'Doomsday Glacier', because its demise would mean significant and irreversible change in Antarctica.

Measurements based on features of cores near both glaciers matched up well enough for the researchers to conclude that they were looking at the effects of large-scale shifts in the Antarctic environment.

"What is especially important about our study is that this change is not random nor specific to one glacier," says geologist Rachel Clark, from the University of Houston.

"It is part of a larger context of a changing climate. You just can't ignore what's happening on this glacier."

Readings from two glaciers were compared. (Clark et al., PNAS, 2024)

Readings from two glaciers were compared. (Clark et al., PNAS, 2024)Together with previous modeling, the findings point to an extreme El Niño climate pattern – a shift in the global weather patterns – that warmed the waters of the west Antarctic between 1939 and 1942, and may well have preceded a significant ice shelf retreat.

These external factors, rather than dynamics within the ice itself, have been enough to cause more of the ice to become free floating rather than attached to the seabed. The retreat of this grounding zone contributes to greater instability and more melting as more of the ice foundation comes in contact with warming waters.

According to the researchers, their study implies that once an ice sheet begins to shrink, melting can continue for decades even if the initial triggers are no longer there. That's an important consideration for scientists studying ice melt.

"It is significant that El Niño only lasted a couple of years, but the two glaciers, Thwaites and Pine Island, remain in significant retreat," says geologist Julia Wellner, from the University of Houston. "Once the system is kicked out of balance, the retreat is ongoing."

It's thought that the Thwaites Glacier has seen a net loss of more than 1,000 billion tons of ice since the turn of the century, and understanding more about how increased melting has been triggered in the past can help us model the scale of problems in the future.

"The glacier is significant not only because of its contribution to sea-level rise but because it is acting as a cork in the bottle holding back a broader area of ice behind it," says Wellner.

"If Thwaites is destabilized, then there's potential for all the ice in West Antarctica to become destabilized."

The research has been published in PNAS.

11 months ago

69

11 months ago

69