ARTICLE AD

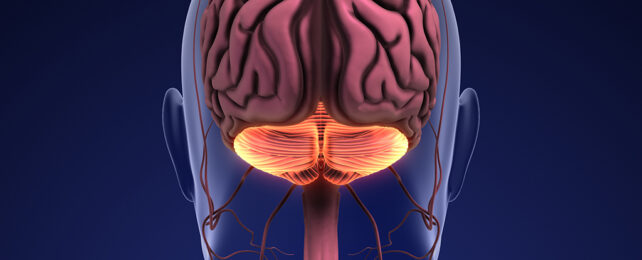

The cerebellum sits at the base of the brain towards the back of the head. (Jitendra Jadhav/Getty Images)

The cerebellum sits at the base of the brain towards the back of the head. (Jitendra Jadhav/Getty Images)

With a name that means 'little brain' in Latin, the cerebellum comprises just 10 percent of the entire brain's mass. Don't let that small size fool you, though; with more than three-quarters of the brain's neurons packed within that small space, there's a lot going on inside.

Traditionally it's thought this part of the nervous system located at the base of the skull is mostly concerned with coordinating motor functions like balance and movement. Now new research backs up a hypothesis that's gathering momentum: it also plays a key role in learning.

In this new study, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and Columbia University wanted to build on previous research identifying the cerebellum's posterior-lateral region as playing a role connecting what we see to the movements we make.

"A long-standing assumption about cerebellar function has been that it only controls how we move," says neurobiologist Andreea Bostan from the University of Pittsburgh.

"However, we now know that there are parts of the cerebellum that are connected and appear to have evolved along with areas of the cerebrum that control how we think."

The team trained monkeys to move either their left hand or their right hand in response to images on a screen, providing juice as a reward when they got the movements right.

Using drugs to temporarily disable the posterior-lateral part of the monkeys' cerebellum significantly affected their learning. Even with the juice reward, the test animals struggled to remember which hand they were supposed to move in reaction to which image. Learning that had already been well consolidated, however, could still be recalled.

"When you inactivate this cerebellar region, you impair new learning," says Bostan. "It's much slower, happens over many more trials, and the performance does not get to the same level."

"This is a concrete example of the cerebellum using reward information to shape cognitive function in primates."

Further tests revealed that the performance of the movements wasn't affected by the posterior-lateral cerebellum being out of action, and switching off other parts of the cerebellum didn't seem to make any difference to the learning process.

All of this is important extra information when it comes to finding out how the brain works and adapts to the world around us – and how we might better tackle the conditions caused by the brain's normal operation somehow breaking down.

"Our research provides clear evidence that the cerebellum is not only important for learning how to perform skillful actions, but also for learning which actions are most valuable in certain situations," says Bostan.

"It helps explain some of the non-motor difficulties in people with cerebellar disorders."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.

8 months ago

51

8 months ago

51