ARTICLE AD

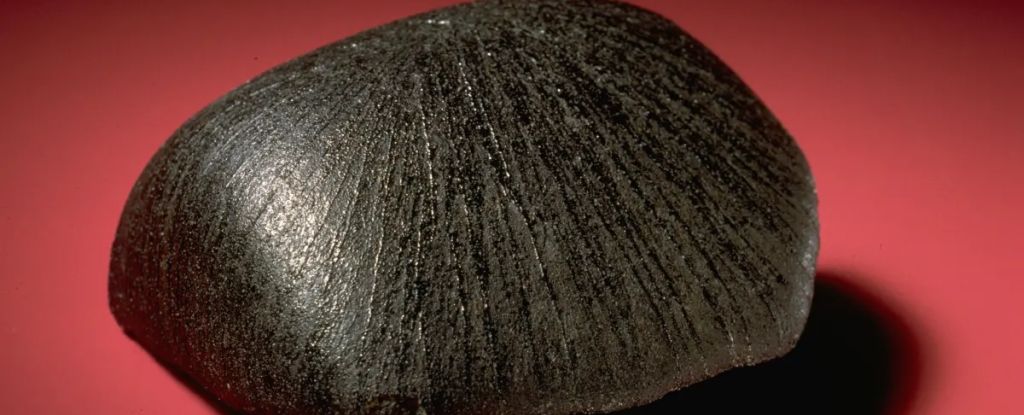

Feast your eyes on a newly discovered species of extinct life, fortuitously fossilized in a mineral that turned the ancient arthropods gold.

Well, gold in color. The fossilized remains belong to an extinct arthropod dubbed Lomankus edgecombei, which died about 450 million years ago and became fossilized in iron pyrite—fool’s gold, a different and admittedly less precious metal than its lustrous yellow counterpart. The unique fossil specimens are described in a paper published today in Current Biology.

“As well as having their beautiful and striking golden colour, these fossils are spectacularly preserved,” said Luke Parry, a paleobiologist at the University of Oxford and lead author of the study, in a university release. “They look as if they could just get up and scuttle away.”

The team of paleontologists found the Lomankus specimens near Rome, New York, in a fossil-rich area known as Beecher’s Bed. Lomankus was an arthropod, distantly related to modern horseshoe crabs and spiders.

Lomankus’ environment in life didn’t have much oxygen, which helped to preserve the specimens in layers of sediment. Eventually, the yellow pyrite replaced the tissues in the Lomankus specimens piecemeal, allowing the paleontological team to reconstruct the animal in 3D some 450 million years later.

A life reconstruction of Lomankus. lllustration: Xiaodong Wang.

A life reconstruction of Lomankus. lllustration: Xiaodong Wang. The team made its 3D images of Lomankus with CT scanning, revealing the unique anatomy of the ancient arthropods. Lomankus was a megacheiran, a group of arthropods with a “great appendage” on the front of their bodies. Calm down: The great appendage was a modified leg that had a “presumed sensory function,” the team wrote in its study.

“There are more species of arthropod than any other group of animals on Earth,” Parry said. “Part of the key to this success is their highly adaptable head and its appendages, that has adapted to various challenges like a biological Swiss army knife.”

The golden Lomankus fossils show the animal’s underbelly, components of its mouth, and thin flagella on its great appendage that the researchers believe it used to sense the environment and find prey. The fossils are rare examples of specimens that are as informative as they are pretty. It may not be Han Solo in carbonite, but it’s real, and gilt, and that makes it just as compelling, if not more so.

There are pyrite deposits across the eastern United States, as indicated by a paper revealed earlier this year at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly. Some pyrite is fooling us twice over, as crystals of the stuff can contain real gold, too. But pyrite may have also have value because it sequesters lithium, a coveted metal for its use in battery technologies.

All that glitters may not be gold, but the gilt fossils from central New York are certainly a special treat for a paleontologist—or anyone who wishes to marvel at the circumstances by which ancient life on our planet can be preserved for nearly half a billion years.

3 weeks ago

48

3 weeks ago

48