ARTICLE AD

Illustration of a healthy neuron (left), neuron with Alzheimer's (center), and a dead neuron being engulfed by microglia (right). (Science Photo Library/Canva)

Illustration of a healthy neuron (left), neuron with Alzheimer's (center), and a dead neuron being engulfed by microglia (right). (Science Photo Library/Canva)

Analysis of human brain tissue revealed differences in how immune cells behave in brains with Alzheimer's disease compared to healthy brains, indicating a potential new treatment target.

University of Washington-led research, published in 2023, discovered microglia in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease were in a pre-inflammatory state more frequently, making them less likely to be protective.

Microglia are immune cells that help keep our brains healthy by clearing waste and preserving normal brain function.

In response to infection or to clear out dead cells, these nifty shape-shifters can become less spindly and more mobile to engulf invaders and rubbish. They also 'prune' synapses during development, which helps shape the circuitry for our brains to function well.

It's less certain what part they play in Alzheimer's, but in people with the devastating neurodegenerative disease, some microglia respond too strongly and may cause inflammation that contributes to the death of brain cells.

Unfortunately, clinical trials of anti-inflammatory medications for Alzheimer's haven't shown significant effects.

Computer Illustration of a synapse between two neurons. (Science Photo Library/Canva)

Computer Illustration of a synapse between two neurons. (Science Photo Library/Canva)To look closer at the role of microglia in Alzheimer's disease, University of Washington neuroscientists Katherine Prater and Kevin Green, along with colleagues from multiple US institutions, used brain autopsy samples from research donors – 12 who had Alzheimer's and 10 healthy controls – to study the gene activity of microglia.

Using a new method to enhance single-nucleus RNA sequencing, the team was able to identify in depth 10 different clusters of microglia in the brain tissue based on their unique set of gene expression, which tells the cells what to do.

Three of the clusters hadn't been seen before, and one of them was more common in people with Alzheimer's disease. This type of microglia has genes turned on that are involved in inflammation and cell death.

Overall, the researchers found that microglia clusters in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease were more likely to be those in a pre-inflammatory state.

This means they were more likely to produce inflammatory molecules that can damage brain cells and possibly contribute to the progression of Alzheimer's disease.

The microglia types in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease were less likely to be protective, compromising their ability to pull their weight in cleaning up dead cells and waste and promoting healthy brain aging.

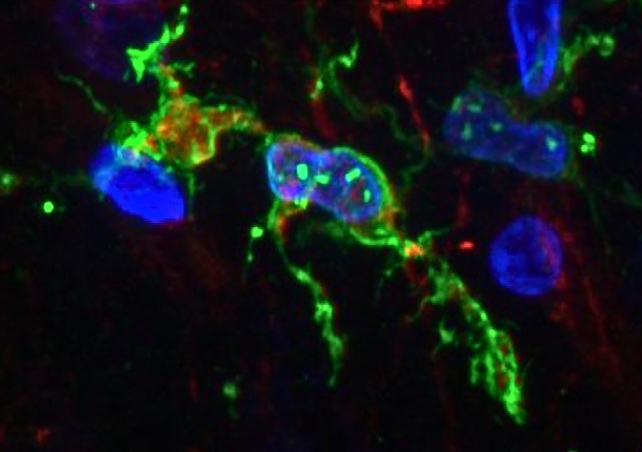

Photomicrograph of microglia (green) from a brain affected by Alzheimer's. (Lexi Cochoit/UW Neuroinflammation Lab)

Photomicrograph of microglia (green) from a brain affected by Alzheimer's. (Lexi Cochoit/UW Neuroinflammation Lab)The scientists also think microglia can change types over time. So we can't just look at a person's brain and say for sure what type of microglia they have; keeping track of how microglia change over time could help us understand how they contribute to Alzheimer's disease.

"At this point, we can't say whether the microglia are causing the pathology or whether the pathology is causing these microglia to alter their behavior," said Prater.

This research is still in its early stages, but it advances our understanding of these cells' role in Alzheimer's disease and suggests certain microglia clusters may be targets for new treatments.

The team is hopeful that their work will lead to the development of new therapies that can improve the lives of people with Alzheimer's disease.

"Now that we have determined the genetic profiles of these microglia, we can try to find out exactly what they are doing and hopefully identify ways to change their behaviors that may be contributing to Alzheimer's disease," Prater said.

"If we can determine what they are doing, we might be able to change their behavior with treatments that might prevent or slow this disease."

The study has been published in Nature Aging.

An earlier version of this article was published in August 2023.

16 hours ago

1

16 hours ago

1