ARTICLE AD

(NASA / Theophilus Britt Griswold / Sander Goossens / Isamu Matsuyama / Gael Cascioli / Erwan Mazarico)

(NASA / Theophilus Britt Griswold / Sander Goossens / Isamu Matsuyama / Gael Cascioli / Erwan Mazarico)

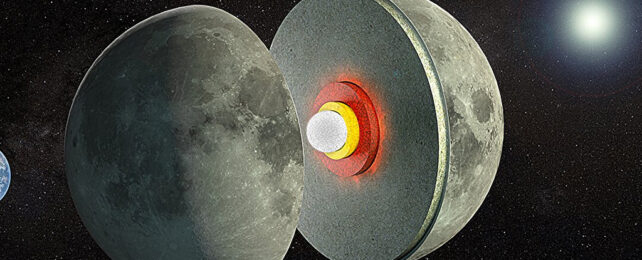

The presence of a partially-molten layer between the Moon's rocky mantle and solid metal core is looking more likely following a study on its changing shape and gravity.

Researchers from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Arizona analyzed new data describing the Moon's rigidity under the gravitational influence of Earth and the Sun, finding its mass is unlikely to be solid all the way through.

Rather, the Moon's mantle has a thick, goopy zone that rises and falls like our tides.

"Interior modeling indicates that these values can be matched only with a low-viscosity zone (LVZ) at the base of the lunar mantle," write the researchers in their published paper.

The idea of this non-solid layer has been floated by researchers for several decades, but up until now the available data hasn't been able to say definitively one way or the other whether this layer is actually there.

Under the influence of Earth's and the Sun's gravitational pull, the Moon experiences a tidal effect – not in terms of oceans, but of physical deformations of the Moon's shape and gravitational field.

For this study, the team used new readings taken by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Those measurements allowed the researchers to estimate the lunar tidal changes on a yearly basis for the first time.

Computer models describing the nature of the rock deep within the Moon's interior as it orbits Earth indicates a layer beneath the solid mantle needs to be at least somewhat viscous for the numbers to fit.

That brings up further questions: how did this zone get there? And what's keeping it hot? Further research is going to be needed to know for sure, but the team behind this study thinks the titanium-iron oxide mineral ilmenite might be involved.

"The presence of an LVZ at the lower base of the lunar mantle may be most readily explained by partial melt in an ilmenite-rich layer, which would make the Moon similar to Mars, where partial melt was recently inferred from the analysis of seismic data," write the researchers.

As with studies of Earth, some guesswork is required to judge what's hundreds and thousands of kilometers below the surface – but it's all very educated guesswork, based on what we know about moons and planets.

We know that the mantle above this LVZ is made largely from the mineral olivine, and that it's had quite a story to tell over several billion years. If we're able to establish a permanent base on the Moon in the coming years, seismic readings taken from the lunar surface itself should be able to tell us more about what's happening below the surface.

"The existence of this zone has profound implications for the Moon's thermal state and evolution," write the researchers.

The research has been published in AGU Advances.

1 month ago

28

1 month ago

28