ARTICLE AD

Humans with relatively more fat hidden in and around their muscles face a higher risk of death or hospitalization from heart disease, according to new research – an association that persists regardless of body mass index (BMI).

The findings highlight the inadequacy of BMI as a marker of heart health and indicate a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease that warrants further study.

"Knowing that intermuscular fat raises the risk of heart disease gives us another way to identify people who are at high risk, regardless of their body mass index," says co-author Viviany Taqueti, director of the Cardiac Stress Laboratory at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

The health effects of fatty muscle remain poorly understood, the authors note, but it has been associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, among other ailments. This is the most exhaustive study so far into fatty muscle's influence on heart disease, they say.

Beyond illuminating that link, the study highlights limitations of metrics like BMI in universally evaluating heart disease risk.

"Obesity is now one of the biggest global threats to cardiovascular health, yet body mass index – our main metric for defining obesity and thresholds for intervention – remains a controversial and flawed marker of cardiovascular prognosis," explains Taqueti

"This is especially true in women, where high body mass index may reflect more 'benign' types of fat."

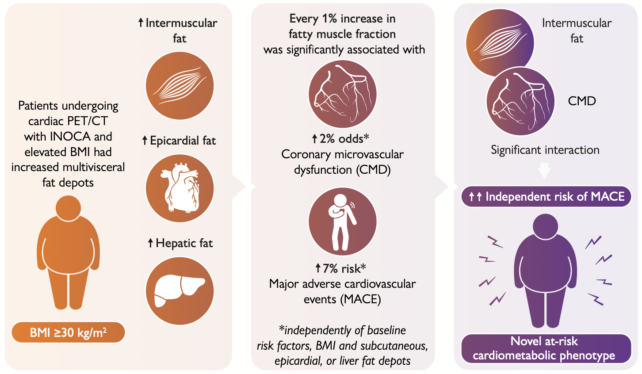

The study found obesity-related cardiovascular risk is not well-captured by BMI. (Souza et al., European Heart Journal, 2025)

The study found obesity-related cardiovascular risk is not well-captured by BMI. (Souza et al., European Heart Journal, 2025)Everyone needs some body fat, of course, including small deposits embedded among our skeletal muscle fibers called intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT).

Intermuscular fat is present in most muscles, but the amount varies between individuals and tends to increase with age. Sometimes, too much intermuscular fat accumulates amid skeletal muscles, a condition known as fat infiltration or myosteatosis.

In previous research, high levels of IMAT have been associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, as well as loss of strength and mobility problems. Yet much remains unknown about IMAT, including how it affects cardiovascular health.

Taqueti and her colleagues looked for a link between muscle quality and coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) – a condition in which small blood vessels serving the heart are damaged – plus other cardiovascular maladies.

"In our research, we analyze muscle and different types of fat to understand how body composition can influence the small blood vessels or 'microcirculation' of the heart, as well as future risk of heart failure, heart attack, and death," Taqueti says.

The study involved 669 subjects, all patients at Brigham and Women's Hospital with chest pain or shortness of breath but no signs of obstructive coronary artery disease. About 70 percent were women and 46 percent were non-white, with an average age of 63, the authors report.

The researchers examined each patient's heart with cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans. They also used CT scans to reveal body composition, measuring amounts and locations of fat and muscle.

Their analysis involved a measurement called the fatty muscle fraction – the ratio of intermuscular fat to skeletal muscle plus intermuscular fat.

Researchers followed up with subjects for about six years, recording any deaths or hospitalizations due to heart attack or heart failure.

Patients with elevated IMAT levels were more likely to have CMD, the study found, and faced a higher risk of death or hospitalization from heart disease.

Every 1 percent increase in fatty muscle fraction conferred a 2 percent higher CMD risk, the researchers report, and a 7 percent higher risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event – regardless of BMI and other known risk factors.

Patients with excess IMAT plus evidence of CMD are in particular danger, the study suggests, with an even higher risk of death, heart attack, and heart failure.

Those with more lean muscle had lower risk, the researchers report. Storing fat elsewhere in the body, like under the skin, didn't increase the risk.

"Compared to subcutaneous fat, fat stored in muscles may be contributing to inflammation and altered glucose metabolism leading to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome," Taqueti says. "In turn, these chronic insults can cause damage to blood vessels, including those that supply the heart, and the heart muscle itself."

The study has some notable limitations, as the authors acknowledge – and as two other researchers outline in an accompanying editorial.

Future research should dig deeper into the link between fatty muscles and heart disease, she says, and investigate how we can use this information to save lives.

The study was published in the European Heart Journal.

3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1