ARTICLE AD

Cutting calories and habitually holding off on meals just might be a winning strategy for stretching out your years, though terms and conditions may apply.

A huge new animal study from the US on nearly 1,000 mice suggests metabolic changes and a reduced body mass are side effects of food restriction that could come at a health cost for some individuals.

Study after study has consistently shown all kinds of animals, from monkeys to fruit flies to mice to nematodes, live longer when their fuel supply is throttled.

But given the ethics and challenges surrounding clinical research, it's hard to say whether eating less might also push the limits of human lifespans.

Observational investigations using less extreme calorie constrictions, such as intermittent fasting, suggest there are benefits to dietary restriction that may reduce our own chances of an untimely end.

Health studies also imply reductions in weight and body fat and mitigated cardiometabolic risks, which may play a strong role in extending life. But small sample sizes and limited periods of study make it hard to say whether these changes are directly responsible for the extended lifespan.

Researchers assessed the effects of graded calorie restrictions and intermittent fasting on 960 genetically diverse female mice, confirming the findings of numerous previous studies, which claim that keeping the body a little hungry from time to time leads to slightly longer lives.

Those on the highest reduction in calories lost, on average, nearly a quarter of the weight they had as a six-month-old mouse by the time they were 18 months old, whereas mice on a typical diet gained just over a quarter of their weight.

Notably, the heavily-restricted mice also lived, on average, around 9 months longer than those on normal diets – a jump of just over a third.

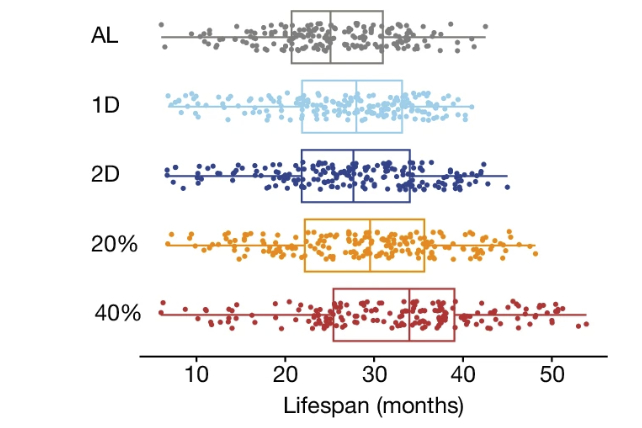

Lifespans of mice on a typical diet (AL); 1 day fasting; 2 day fasting; 20 percent calorie restriction; 40 percent calorie restriction (Francesco, et al., Nature, 2024).

Lifespans of mice on a typical diet (AL); 1 day fasting; 2 day fasting; 20 percent calorie restriction; 40 percent calorie restriction (Francesco, et al., Nature, 2024).What the averages don't show is the variation within each of the calorie controlled groups. While the spread of ages within the heavily-restricted population extended well beyond those of their peers, a number of mice died at different ages, almost as if negative forces swamped any benefits they may have had from living on fewer calories.

In fact, within the calorie-restricted groups it was mice that held onto the most weight that tended to die later, suggesting metabolic regulation is unlikely to explain why calorie-restricted mice lived longer.

Genetics, the authors report, played a far greater role in determining which mice lived to see a ripe old age. Mice that retained weight through stressful handling had a strong chance of living longer, as did those with a greater proportion of infection-fighting white blood cells, and a lower variation in red blood cell size.

Put plainly, a resilient, well-stocked mouse was more likely to survive the rough and tumble of life's pressures and live longer.

Just why regular fasting or reduced calories helped some mice live longer is an ongoing question. No doubt it's a complex interplay of factors, evidently more removed from weight loss and metabolism than we thought.

Keeping in mind the potential for differences between mouse and human physiology, the study should give pause to how we think about our diet, health, and lifespan.

That's not to say there's no place for using diet restrictions to keep one's metabolism in order. Even if our genes have the ultimate say in our chances of seeing our 99th birthday, maintaining good health throughout our lives is arguably as important as piling on the years, if not more so.

This research was published in Nature.

1 month ago

14

1 month ago

14