ARTICLE AD

Olympic hockey player Hugo Inglis is one of several athletes concerned by the data. (Kiyoshi Ota/Getty Images)

Olympic hockey player Hugo Inglis is one of several athletes concerned by the data. (Kiyoshi Ota/Getty Images)

Scientists and athletes are concerned that heat extremes may coincide with Olympic and Paralympic competition dates, with potentially lethal results.

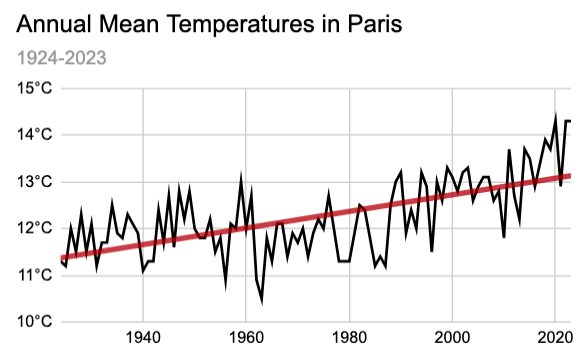

The last time Paris hosted the Olympics was a century ago. Since then, average temperatures have increased by 1.8 °C, with 50 heat waves occurring between 1947 and 2023, a new report explains.

In the summer of 2003, a deadly heat wave killed more than 14,000 people in France. These extremes are ten times more likely as a result of climate change, which has increased the risk of heat-related mortality in central Paris by 70 percent.

"The fact that the Olympics will take place during high summer means that the threat of a devastating hot spell is a very real one," states the report, which was co-produced by the British Association for Sustainable Sport and climate advocacy group FrontRunners.

Average temperatures in Paris have increased by about 1.8 °C since the last time the city hosted the Olympics. (Météo France, 2023)

Average temperatures in Paris have increased by about 1.8 °C since the last time the city hosted the Olympics. (Météo France, 2023)Physiologists Mike Tipton and Jo Corbett from the Extreme Environments Laboratory at the University of Portsmouth in England warn the Games may expose athletes to conditions that could impair their performance, and at worst, put them at risk of death.

"Hot and/or humid conditions make it harder to lose heat to the environment and more difficult to regulate deep-body (core) temperature," they explain.

"This impairs physical performance, particularly when the exposure is prolonged and sustained high work rates are required."

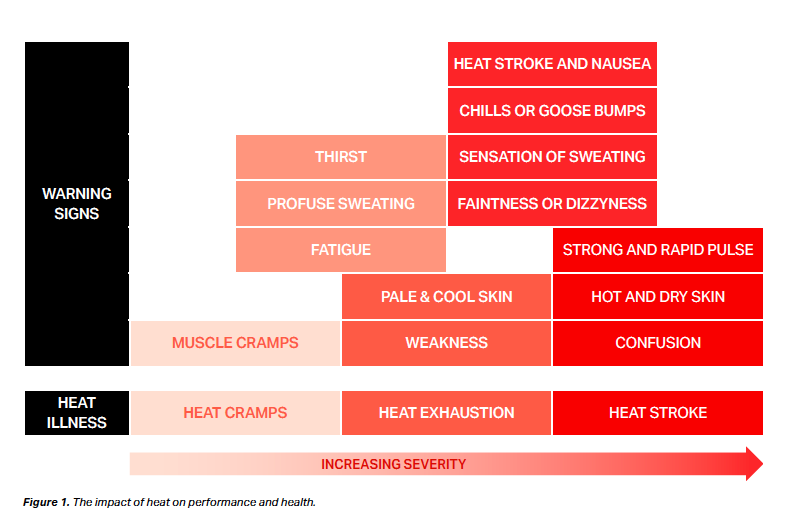

Competing in severe heat has serious consequences. (Rings of Fire: Heat Risks at the 2024 Paris Olympics, 2024)

Competing in severe heat has serious consequences. (Rings of Fire: Heat Risks at the 2024 Paris Olympics, 2024)One of the most widely used ways to measure the body's experience of hot environments is called the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT).

WBGT gives a more specific read on the conditions an athlete will face than air temperature alone. It also factors in humidity using a thermometer with a wet wick over its bulb, air movement, and radiant heat (usually from the sun).

Higher humidity makes a big difference to the body's ability to remove heat via sweat.

A study published in 2022 found the maximum WBGT that young, healthy humans can tolerate before they can no longer regulate their body temperature is around 31 °C (88 °F), which would occur if the air temperature was around 30 °C on a day with very high humidity.

High levels of ambient heat and humidity, which are more likely to occur in Parisian summers now than ever before, increase the risk of sunburn, heat cramps, exhaustion, and even collapse from heat stroke.

To mitigate athletes' exposure to heat stress, sporting authorities set WBGT limits for events, though there are concerns they may not be strict enough to adequately protect competitors in a warming world.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

In tennis, a WBGT of 30.1 °C activates an 'Extreme Weather Policy', meaning a 10-minute break is taken. If the WBGT reaches 32.2 °C, the tournament officials may suspend play.

The triathlon will be canceled if the WBGT index exceeds 32.2 °C. Meanwhile, hockey has no specific WBGT limit; instead, air temperatures need to reach at least 35 °C before any safety measures are activated.

A 2023 study noted hockey was one of the high-athletic endurance sports affected by heat during the Tokyo Olympics in 2020.

"During the Games, at least one hockey athlete suffered heat stroke, while another three reported heat-related illnesses," the new report states.

"Given this, it is particularly concerning that – despite the threat of heatwaves during the Paris Olympics – the International Hockey Federation (FIH) is only allowing reserves to be drawn from the 16-person squads."

Hockey player Hugo Inglis will be a fourth-time Olympian in Paris this summer and knows the impacts of heat stress firsthand. His team experienced three hamstring tears at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which he believes were the result of pre-match ice baths taken to help the players push on in sweltering conditions.

Inglis is concerned that many athletes are "too afraid to speak out about having to play in such grueling conditions because of concerns about how they might be perceived."

The report calls for governing bodies to review event scheduling to avoid heat extremes, improve safety protocols, reassess fossil fuel sponsorship, and empower athletes to speak up about how climate change is affecting their sport.

The full report, titled "Rings of Fire: Heat Risks at the 2024 Paris Olympics" is available here.

4 months ago

17

4 months ago

17