ARTICLE AD

We've just seen concrete confirmation that galaxies could collide and grow in the early Universe.

Scientists have finally caught two blazing quasars – galaxies powered by supermassive black holes – in the very act of merging together in the Cosmic Dawn just 900 million years after the Big Bang.

It's the first colliding quasar pair we've found in this epoch. A time of intense cosmic formation in the wake of the Big Bang, this period should be positively riddled with merging galaxies, but previous searches have only turned up loners.

Astronomers are relieved and gratified to have finally found one – a detection that could help reveal more galactic collisions in the Cosmic Dawn, now that we have an example that shows us what to look for.

"The existence of merging quasars in the Epoch of Reionization has been anticipated for a long time," explains astronomer Yoshiki Matsuoka of Ehime University in Japan. "It has now been confirmed for the first time."

Quasars are among the brightest objects in the Universe. They are galaxies in which the supermassive black hole is feeding at a tremendous rate: a gargantuan cloud of dust and gas surrounds it, from which the black hole therein is positively guzzling. This process produces vast amounts of blazing light from the frictional and gravitational forces acting on the cloud, causing it to shine.

Scientists believe that quasars can form when two galaxies merge, a process that results in a higher concentration of material in the galactic center. And we've seen a lot of evidence of past and ongoing mergers in the more recent Universe, including galactic centers with two or more supermassive black holes on a slow, spiraling collision course.

Because of this, and because we've found a lot of quasars in the early Universe (partly because they're brighter and therefore easier to see), cosmologists expect a high rate of galaxy mergers during the Cosmic Dawn.

This, in turn, would help us understand an early Universe period known as the Epoch of Reionization, in which powerful light ionized the foggy neutral hydrogen, causing it to clear and allowing light to stream freely.

But actually finding these mergers has proven extremely tricky.

In fact, the discovery was quite accidental. Matsuoka and colleagues were poring over data collected using the Subaru Telescope when they found something unusual.

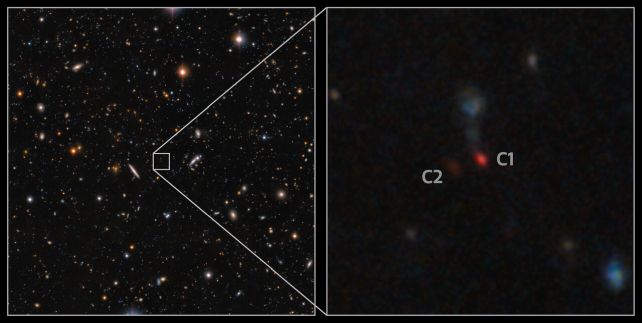

Image of the two objects captured by the Subaru Telescope. (NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/T.A. Rector, D. de Martin & M. Zamani)

Image of the two objects captured by the Subaru Telescope. (NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/T.A. Rector, D. de Martin & M. Zamani)"While screening images of quasar candidates I noticed two similar and extremely red sources next to each other," Matsuoka says. "The discovery was purely serendipitous."

A pair of red blobs side-by-side could be any one number of things. For example, the light of a single object can be split and duplicated by the gravitational warping of space-time between the source and the viewer, causing a single object to look like two or more.

So the researchers conducted follow-up observations using the Subaru Telescope and Gemini North, as well as the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA).

These observations revealed that not only were the objects real and very far away, but were right next to each other, separated by a gap of just 40,000 light-years.

The team also found that a significant proportion of the light emitted by the galaxies is from star formation, and that a bridge of gas connects them, revealing that the two are interacting – and in the process of merging.

Each also appears to host a supermassive black hole some 100 million times the mass of the Sun. That's huge for the early Universe – even the Milky Way's central black hole is just 4.3 million solar masses.

It's a spectacular discovery, and one that promises more of the same in the future. Meanwhile, the researchers are working on analyzing the ALMA observations to characterize the dust and gas that surrounds the two galaxies. The findings will be published in a separate paper.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

5 months ago

36

5 months ago

36