ARTICLE AD

As more funding flows into deep tech to address difficult global problems like climate change, PhD entrepreneurs coming out of Europe’s top universities and labs are increasingly turning their research into companies.

French spinout Diamfab, founded in 2019, is one example. Its co-founders, CEO Gauthier Chicot and CTO Khaled Driche, both PhDs in nanoelectronics and recognized researchers in the field of semiconducting diamond, left Institut Néel, a laboratory of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), with two licensed patents under their belt.

Since then, Chicot and Driche have registered more patents and brought on a third co-founder, Ivan Llaurado, as their chief revenue officer and partnership director. They also raised an €8.7 million round of funding from Asterion Ventures, Bpifrance’s French Tech Seed fund, Kreaxi, Better Angle, Hello Tomorrow and Grenoble Alpes Métropole.

This interest comes because the paradigm around semiconducting diamonds has changed in the last two years. “Diamonds are no longer a laboratory subject: They have become an industrial reality, with startups, with manufacturers interested in this field, and with the partners we have around us,” Chicot told TechCrunch.

Getting out of the lab

Silicon is still the most widely used semiconductor material in electronics because it’s ubiquitous and cheap. But there’s hope other options could someday outperform it, and not just in labs. Tesla’s decision to use silicon carbide instead of silicon was an important step in that direction, and diamond could be next.

Because diamond is naturally more resistant to high temperatures and more energy-efficient, Diamfab envisions a future in which a given component will need a much smaller surface of synthetic diamond than of silicon carbide, which will make it competitive on price.

The firm’s long-term goal is to make more efficient semiconductors with a lower carbon footprint, while also supporting what Chicot refers to as “the electrification of society,” starting with transportation.

Diamond-based electronics open the door to applications in the field of power electronics — think of smaller batteries and chargers with more autonomy, because less temperature control is required, which is particularly relevant for the automotive sector and electric mobility. But diamond wafers could also be leveraged for nuclear batteries, space tech and quantum computing, too.

The case for diamond as a better alternative to silicon doesn’t come out of nowhere; Diamfab is building on the Institut Néel’s 30 years of R&D into synthetic diamond growth. Its founders wanted to take this technology out of the lab. “We wanted to be useful pioneers,” Chicot said.

Being awarded the Jury’s Grand Prize of i-Lab in 2019 was a turning point for the firm. Co-organized by French institutions, it brought grants and a sense of validation that helped the team inwards and outwards.

With this seal of approval, “banks trust you even if you don’t generate any sales,” Chicot said.”It was a real plus in the beginning to get this award. And it was partly because we have great technology, and partly because it’s technology that’s crucial for the world.”

Diamond promises

French public sector investment bank Bpifrance, one of the organizers of the i-Lab awards, is doubling down on Diamfab with funding from the French Tech Seed fund, which Bpifrance manages on behalf of the French government as part of the France 2030 plan.

When silicon has become a commodity, Diamfab’s high-value-added diamond wafers could be made in Europe and sold at a premium warranted by their higher efficiency, which also ties into the green transition. Decarbonization is one key goal of France 2030, and diamonds could help.

Their carbon footprint would be lighter because of the smaller surface that diamond requires compares to silicon carbide, but also because Diamfab synthetizes its diamonds from methane. In the future, this source could be biomethane, giving a commercial outlet to this byproduct of recycling.

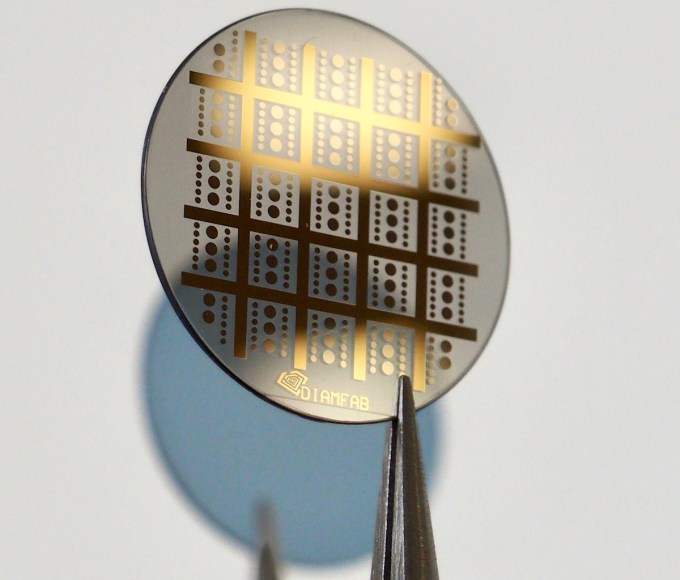

Image Credits: Diamfab

Most of this, however, is still in the future. Diamfab is not decades away from its goals, but says it will need five years for its technology to be able to support the mass production of diamond wafers that fit industry requirements. This means taking its know-how in growing and doping diamond layers on one-inch wafers, and applying it to the four-inch wafers that silicon carbide already works on. Even with enough funding to support a small pilot production line, this will take a few years.

This five-year horizon made Diamfab a no-go for some VCs; while these may be sympathetic to the idea of reindustrializing Europe with cutting-edge innovation, their liquidity cycles make these types of investments more difficult. But Chicot ultimately managed to round up the €8.7 million that will help the startup go through its pre-industrialization phase.

Grenoble, a deep tech hub

The group of investors that have rallied around Diamfab is “balanced,” Chicot said, including public players, evergreen fund Asterion Labs, and supporters of Diamfab’s region, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, and its city of Grenoble.

While there’s warranted hype around AI in Paris, Grenoble may be the closest to a French Silicon Valley. In no small part thanks to Nobel Prize-winning physicist Louis Néel, the Alpine city’s focus on electronics turned it into a deep tech hub that’s now also part of the conversation on both green tech and sovereign tech.

Grenoble startups that pop to mind include Verkor, which secured more than €2 billion for its gigafactory in Northern France, and Renaissance Fusion, which raised $16.4 million last year to build nuclear fusion technology in Europe. But Diamfab may benefirt more from its partnerships with larger players with local ties, including CEA, Schneider Electric, Soitec and STMicroelectronics.

There’s no doubt that more semiconductors will come out of the French Alps. As both the EU and the U.S. adopted Chip Acts to reduce their dependency in Asia, France is set to provide €2.9 billion in aid for the upcoming joint factory of STMicroelectronics and GlobalFoundries, and Soitec recently opened a fourth factory nearby. Now Diamfab hopes it can play a part, too, and unleash the full potential of diamond in semiconductors.

7 months ago

49

7 months ago

49