ARTICLE AD

The idea that having kids can keep you young might have some scientific basis. A study of more than 37,000 adults has found that parenting can help keep the human brain fit as it ages.

For each additional child that a mother or father has, scientists found a boost in brain connectivity that runs counter to what is typically seen in middle- or late-life.

This was especially true in regions of the central nervous system associated with movement and sensation.

The authors of the study, led by cognitive neuroscientist Edwina Orchard at Yale University, claim their research is the largest investigation of parental brain function to date, and the first to show differences in males beyond early fatherhood.

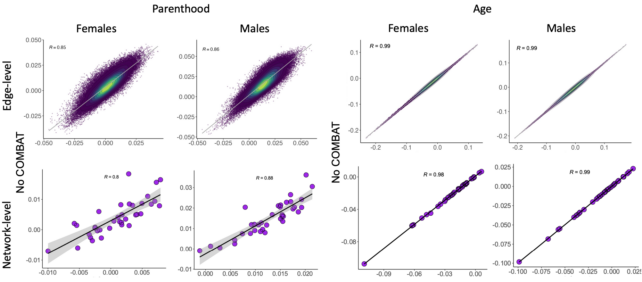

Scatter plots examining the association between connectivity and parenthood (left) and

Scatter plots examining the association between connectivity and parenthood (left) andconnectivity and age (right). Results are present at both edge (top row) and network (bottom row) levels. (Ochard et al., PNAS, 2025)

The findings, which come from the United Kingdom Biobank, suggest that despite the exhaustion, stresses, and challenges of parenting, having kids may enrich a person's life in the long run, providing much-needed cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and social interaction.

"The caregiving environment, rather than pregnancy alone, appears important since we see these effects in both mothers and fathers," says psychiatrist Avram Holmes from Rutgers University.

If that's true, it's possible that the direct impact of caregiving could bestow similar benefits to grandparents, childcare workers, or any other person with a strong responsibility for children.

Fathers are often excluded from studies on parenthood because they don't physically carry a pregnancy, give birth, or breastfeed, but that doesn't mean they aren't profoundly affected by their new household role.

Having children has a life-changing impact on both the body and mind, and yet neuroscientists know little about the long-term brain effects of parenthood in either sex.

Only recently have studies shown the profound brain changes that occur during pregnancy. After a baby is born, MRI scans reveal the brain architecture of mothers changes in areas involved in contemplation and daydreaming, possibly explaining the symptom of 'baby brain'.

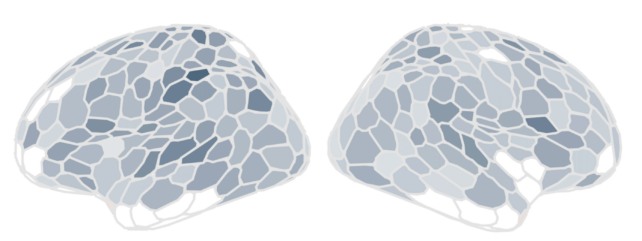

Widespread cortical gray matter volume change occurred in step with advancing gestational week. Darker colors indicate regions most affected by the pregnancy transition. (Laura Pritschet)

Widespread cortical gray matter volume change occurred in step with advancing gestational week. Darker colors indicate regions most affected by the pregnancy transition. (Laura Pritschet)Among first-time fathers, initial research suggests having a child can lead to a loss of one or two percent of cortical volume. Because this shrinkage occurs in a region associated with parental acceptance and warmth, researchers suspect it is the brain's way of refining this network for a new role in life.

But what about after a baby has grown up?

To explore the later impacts of parenthood, cognitive neuroscientist Edwina Orchard led a study at Yale University, combed through the brain scans of nearly 20,000 females and more than 17,600 males in the UK Biobank over the age of 40.

For both sexes, parenthood was positively correlated with functional connectivity, which refers to neural activation patterns within and between brain networks.

Typically, an aging brain shows lower functional connectivity across the somato/motor network and higher connectivity within cortico-subcortical systems.

The opposite patterns were seen among parents between 40 and 69 years of age.

"The regions that decrease in functional connectivity as individuals age are the regions associated with increased connectivity when individuals have had children," explains Holmes.

These younger-looking brain structures are intriguing, but Holmes, Orchard, and their colleagues say larger and more diverse long-term brain studies are needed to tease apart all the various contributing factors that could be impacting how we age.

The study was published in PNAS.

10 hours ago

3

10 hours ago

3