ARTICLE AD

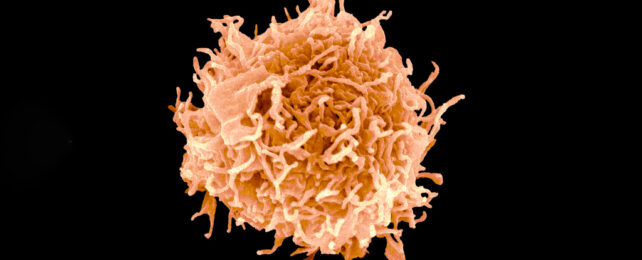

Vaccines teach our immune system's B cells (pictured) what to target. (Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library/Brand X Pictures/Getty Images)

Vaccines teach our immune system's B cells (pictured) what to target. (Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library/Brand X Pictures/Getty Images)

If the effects don't fade too rapidly, new data suggests regular COVID-19 vaccinations could strengthen our immune systems against future variants and even related viruses. This is on top of the proven protection they already provide against current infections.

With thousands of people still being hospitalized each day, more and more of us battling long COVID, and new variants continuing to rapidly emerge, this is hopeful news.

"These data suggest that if these cross-reactive antibodies do not rapidly wane – we would need to follow their levels over time to know for certain – they may confer some or even substantial protection against a pandemic caused by a related coronavirus," explains Washington University immunologist Michael Diamond.

Other vaccinations, such as those for the flu, are not necessarily made more effective by booster shots. Initial vaccinations prompt our immune system to create antibodies to recognize and fight an invasive virus. The details of the antibody are carried by memory immune cells, which help keep watch for and sound the alarm if the virus reappears, quickly producing more of the specific antibodies to defend against it.

When it comes to the flu, these cells are then so good at their jobs, they overwhelm our attempts to introduce updated antibodies through subsequent vaccinations. This is problematic as it leaves little chance for our bodies to store the more updated antibodies' details in memory B cells, weakening our response to future viral variants.

There was some concern this would occur with COVID-19 vaccines, too. So, using a mouse model and human volunteers who had contracted SARS-CoV-2, Washington University immunologist Chieh-Yu Liang and colleagues examined the memory B cell antibodies after different combinations of vaccines.

Incredibly, the researchers found that across doses, the response of the immune system to variants of the virus grows stronger, which is a sign of positive imprinting. In both humans and mice, rather than seeing antibodies specific to any one variant, the researchers found the majority of the antibodies reacted to both tested COVID-19 strains – the original and omicron.

Further tests in mice revealed not only could the antibody response deal with a panel of different SARS-CoV-2 strains, but it could also help subdue SARS-CoV-1 as well, which derives from the 2002 to 2003 epidemic.

"In principle, imprinting can be positive, negative or neutral," explains Diamond. "In this case, we see strong imprinting that is positive, because it's coupled to the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies with remarkable breadth of activity."

Questions about the longevity of the antibodies in our system still remain, as the researchers only tested the immune response one month after the latest booster. What's more, the study only focused on mRNA vaccines, so the results may not be the same in other types of vaccines. Additionally, human studies were limited, so further work is required to see if these results hold true more broadly, particularly in children.

But since uncertainty around COVID-19 vaccines early on in the pandemic, these shots have saved at least tens of millions of lives. What's more, massive studies have decisively demonstrated that the severe risks from the vaccines are extremely rare, especially in comparison to the ongoing and accumulative risks from contracting the virus.

The new study suggests we now have even more reason to keep up those regular boosters.

"At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world population was immunologically naïve, which is part of the reason the virus was able to spread so fast and do so much damage," says Diamond. "We do not know for certain whether getting an updated COVID-19 vaccine every year would protect people against emerging coronaviruses, but it's plausible."

This research was published in Nature.

6 months ago

37

6 months ago

37