ARTICLE AD

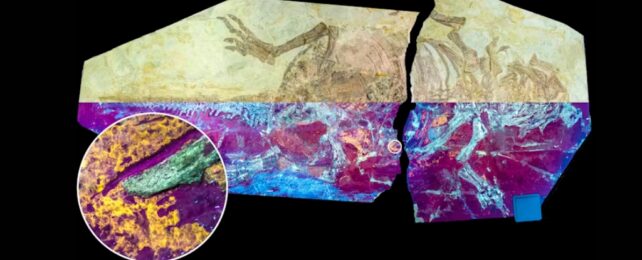

The studied Psittacosaurus under natural (upper half) and UV light (lower half). (Zixiao Yang, Author provided)

The studied Psittacosaurus under natural (upper half) and UV light (lower half). (Zixiao Yang, Author provided)

Strong but light, beautiful and precisely structured, feathers are the most complex skin appendage that ever evolved in vertebrates.

Despite the fact humans have been playing with feathers since prehistory, there's still a lot we don't understand about them.

Our new study found that some of the first animals with feathers also had scaly skin like reptiles.

Following the debut of the first feathered dinosaur, Sinosauropteryx prima, in 1996, a surge of discoveries has painted an ever more interesting picture of feather evolution.

We now know that many dinosaurs and their flying cousins, the pterosaurs, had feathers. Feathers came in more shapes in the past – for example, ribbon-like feathers with expanded tips were found in dinosaurs and extinct birds but not in modern birds. Only some ancient feather types are inherited by birds today.

Paleobiologists have also learnt that early feathers were not made for flying. Fossils of early feathers had simple structures and sparse distributions on the body, so they may have been for display or tactile sensing.

Pterosaur fossils suggest they may have played a role in thermoregulation and in colour patterning.

Fascinating as these fossils are, ancient plumage tells only part of the story of

feather evolution. The rest of the action happened in the skin.

The skin of birds today is soft and evolved for the support, control, growth and pigmentation of feathers, unlike the scaly skin of reptiles.

Fossils of dinosaur skin are more common than you think. To date, however, only a handful of dinosaur skin fossils have been examined on a microscopic level.

These studies, for example a 2018 study of four fossils with preserved skin, showed that the skin of early birds and their close dinosaur relatives (the coelurosaurs) was already very much like the skin of birds today. Bird-like skin evolved before bird-like dinosaurs came around.

So to understand how bird-like skin evolved, we need to study the dinosaurs that branched off earlier in the evolutionary tree.

Our study shows that at least some feathered dinosaurs still had scaly skin, like reptiles today. This evidence comes from a new specimen of Psittacosaurus, a horned dinosaur with bristle-like feathers on its tail.

Psittacosaurus lived in the early Cretaceous period (about 130 million years ago), but its clan, the ornithischian dinosaurs, diverged from other dinosaurs much earlier, in the Triassic period (about 240 million years ago).

In the new specimen, the soft tissues are hidden to the naked eye. Under ultraviolet light, however, scaly skin reveals itself in an orange-yellow glow. The skin is preserved on the torso and limbs which are parts of the body that didn't have feathers.

These luminous colours are from silica minerals that are responsible for preserving the fossil skin. During fossilisation, silica-rich fluids permeated the skin before it decayed, replicating the skin structure with incredible detail. Fine anatomical features are preserved, including the epidermis, skin cells and skin pigments called melanosomes.

The fossil skin cells have much in common with modern reptile skin cells. They

share a similar cell size and shape and they both have fused cell boundaries – a

feature known only in modern reptiles.

The distribution of the fossil skin pigment is identical to that in modern crocodile scales. The fossil skin, though, seems relatively thin by reptile standards. This suggests the fossil scales in Psittacosaurus were also similar in composition to reptile scales.

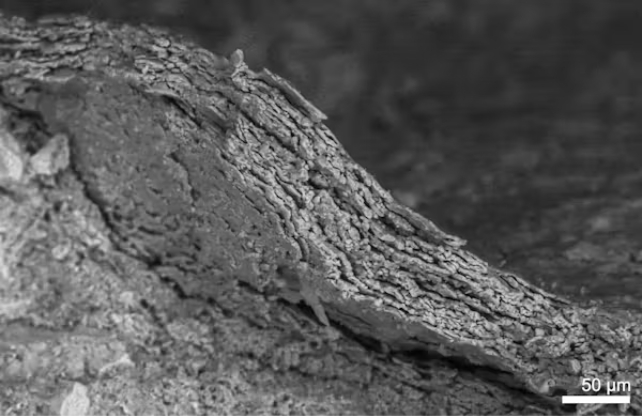

Layers of fossil skin cells. (Zixiao Yang/Author provided)

Layers of fossil skin cells. (Zixiao Yang/Author provided)Reptile scales are hard and rigid because they are rich in a type of skin-building protein, the tough corneous beta proteins. In contrast, the soft skin of birds is made of a different protein type, the keratins, which are the key structural material in hair, nails, claws, hooves and our outer later of skin.

To provide physical protection, the thin, naked skin of Psittacosaurus must have been composed of tough reptile-style corneous beta proteins. Softer bird-style skin would have been too fragile without feathers for protection.

Collectively, the new fossil evidence indicates that Psittacosaurus had reptile-style skin in areas where it didn't have feathers. The tail, which preserves feathers in some specimens, unfortunately did not preserve any feathers or skin in our specimen.

However, the tail feathers on other specimens show that some bird-like skin features must have already evolved to hold feathers in place. So our discovery suggests that early feathered animals had a mix of skin types, with bird-like skin only in feathered regions of the body, and the rest of the skin still scaly, like in modern reptiles.

This zoned development would have ensured that the skin protected the animal against abrasion, dehydration and pathogens.

What next?

The next knowledge gap for scientists to explore is the evolutionary transition from the reptile-style skin of Psittacosaurus to the skin of other more heavily feathered dinosaurs and early birds.

We also need more experiments studying the process of fossilisation itself. There is a lot we don't understand about how soft tissues fossilise, which means it is difficult to tell which skin features in a fossil are real biological features and which are simply artefacts of fossilisation.

Over the last 30 years, the fossil record has surprised scientists in regard to feather evolution. Future discoveries of fossil feathers may help us understand how dinosaurs and their relatives evolved flight, warm-blooded metabolisms, and how they communicated with each other.![]()

Zixiao Yang, Postdoctoral researcher, University College Cork and Maria McNamara, Professor, Palaeobiology, University College Cork

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

7 months ago

52

7 months ago

52