ARTICLE AD

Just like fingerprints and snowflakes, no two galaxies in the entire Universe are exactly alike. But a new discovery 567 million light-years away really is jaw-droppingly unique.

There, astronomers have found a galaxy girdled by, not one, but nine concentric rings – the aftermath of a violent encounter with a blue dwarf galaxy that shot right through its heart, sending shockwaves rippling out into space.

Officially named LEDA 1313424, this galaxy has been given the appropriate title of the Bullseye Galaxy, and its serendipitous discovery is a new window into galaxy-on-galaxy crime.

The Bullseye Galaxy. The blue dwarf galaxy that punched through its center is on the left. (NASA, ESA, Imad Pasha/Yale, Pieter van Dokkum/Yale)

The Bullseye Galaxy. The blue dwarf galaxy that punched through its center is on the left. (NASA, ESA, Imad Pasha/Yale, Pieter van Dokkum/Yale)"We're catching the Bullseye at a very special moment in time," says astronomer Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University. "There's a very narrow window after the impact when a galaxy like this would have so many rings."

So-called ring galaxies are extremely rare in the Universe, and they are thought to be the result of a very specific set of circumstances. Although space is mostly empty, galaxies are drawn together along filaments of the cosmic web, resulting in more collisions between them than you might expect.

Interactions between galaxies can take many forms, and produce varied results. Ring galaxies – such as the mysterious and famous Hoag's Object – are thought to be the result of a collision in which one galaxy blasts straight through the center of another.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

The Bullseye Galaxy has confirmed that this process does indeed take place.

Not far from the larger galaxy is a smaller one, seen in visible light images using the Hubble Space Telescope. Observations taken using the Keck Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI), which is optimized for visible blue wavelengths, revealed that this smaller galaxy is not only close to Bullseye, at a distance of just 130,000 kilometers (about 80,000 miles), but linked.

"KCWI provided the critical view of this companion galaxy that we see in projection near the bullseye," says astronomer Imad Pasha of Yale University.

"We found a clear signature of gas extending between the two systems, which allowed us to confirm that this galaxy is in fact the one that flew through the center and produced these rings."

"The data from KCWI that identified the 'dart' or impactor is unique. There hasn't been any other case where you can so clearly see the gas streaming from one galaxy to the other, " van Dokkum adds.

"That there is all this gas right between the velocity of one galaxy and the other is the key insight, showing that material is being pulled out of one galaxy, left behind by the other, or both. It physically fills up the entire space. The KCWI data enables us to see the tendril of gas that is still connecting these two galaxies."

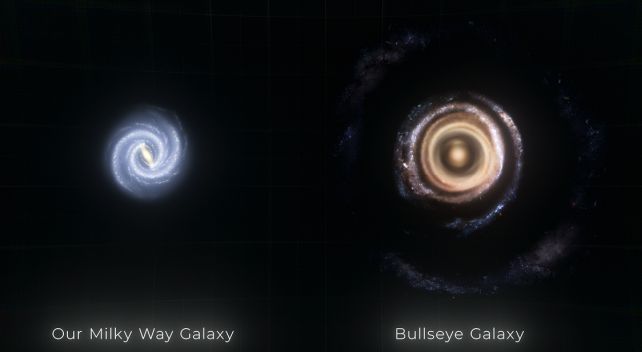

An artist's impression of the Milky Way next to the Bullseye Galaxy for size comparison. (NASA, ESA, Ralf Crawford/STScI)

An artist's impression of the Milky Way next to the Bullseye Galaxy for size comparison. (NASA, ESA, Ralf Crawford/STScI)The rings are regions of higher density, where the galactic material has been pushed together by the rippling shocks. The clumping of the dust and gas triggers star formation, resulting in higher star density, which is why the rings glitter so brightly.

The most distant ring is relatively faint and tenuous, and was only spotted in the KCWI images, at quite a distance from the main body of the galaxy. The entire galaxy is 250,000 light-years across.

That gap between the rings is a marvel, showing that the rings propagate outwards in almost exactly the same way as predicted by theory, with the first two rings spreading quickly, with the subsequent rings forming later.

An artist's diagram of the ring distribution in the Bullseye Galaxy. (NASA, ESA, Ralf Crawford/STScI)

An artist's diagram of the ring distribution in the Bullseye Galaxy. (NASA, ESA, Ralf Crawford/STScI)It's like dropping a pebble in a pond.

"If we were to look down at the galaxy directly, the rings would look circular, with rings bunched up at the center and gradually becoming more spaced out the farther out they are," Pasha says.

The data provided by this marvelous galaxy will help astronomers adjust their models and theories, to better understand how such collisions play out. The researchers also hope future observations with upcoming telescopes will ferret out even more ring galaxies, lurking out there in the wide expanses of the cosmos.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

3 hours ago

5

3 hours ago

5