ARTICLE AD

Hurricane Beryl was the latest Atlantic storm to rapidly intensify, growing quickly from a tropical storm into the strongest June hurricane on record in the Atlantic.

It hit the Grenadine Islands with 150 mph winds and a destructive storm surge on July 1, 2024, then continued to intensify into the basin's earliest Category 5 storm on record.

The damage Beryl caused, particularly on Carriacou and Petite Martinique, was extensive, Grenada Prime Minister Dickon Mitchell told a news briefing. "In half an hour, Carriacou was flattened."

Beryl's strength and rapid intensification were unusual for a storm so early in the season. This year, that is especially alarming as forecasters expect an exceptionally active Atlantic hurricane season.

Rapidly intensifying storms can put coastal communities in great danger and leave lasting scars. In 2022, for example, Hurricane Ian devastated portions of Florida after it rapidly intensified. To this day, residents are still recovering from the effects.

As Beryl continued across the Caribbean Sea on July 2, Jamaica and the Cayman Islands were under hurricane warnings.

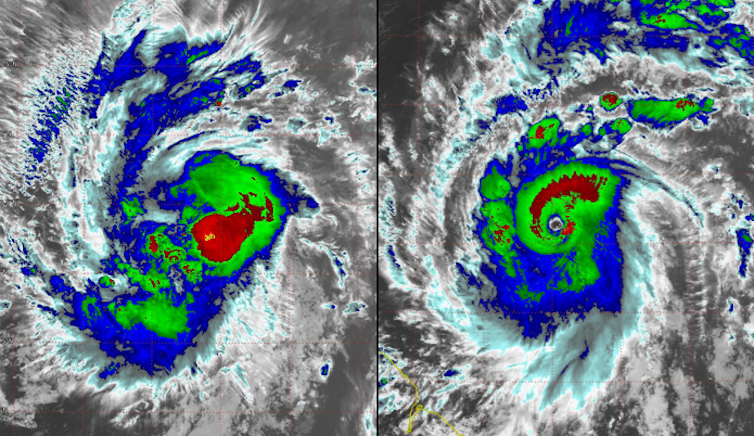

Two satellite images of Beryl taken on June 29, left, and June 30: As Beryl rapidly intensified, an eye formed, and deep thunderstorms wrapped around it. (Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere)

Two satellite images of Beryl taken on June 29, left, and June 30: As Beryl rapidly intensified, an eye formed, and deep thunderstorms wrapped around it. (Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere)What causes hurricanes to rapidly intensify, and has climate change made rapid intensification more likely?

I research hurricanes, including how they form and what causes them to intensify, and am part of an initiative sponsored by the U.S. Office of Naval Research to better understand rapid intensification.

I also work with scientists at the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration to analyze data collected by reconnaissance aircraft that fly into hurricanes. Here's what we're learning.

How did Hurricane Beryl intensify so quickly?

Rapid intensification occurs when a hurricane's intensity increases by at least 35 mph over a 24-hour period. Beryl far exceeded that threshold, jumping from tropical storm strength, at 70 mph, to major hurricane strength, at 130 mph, in 24 hours.

A key ingredient for rapid intensification is warm water. The ocean temperature must be greater than 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27 Celsius) extending more than 150 feet below the surface. This reservoir of warm water provides the energy necessary to turbocharge a hurricane.

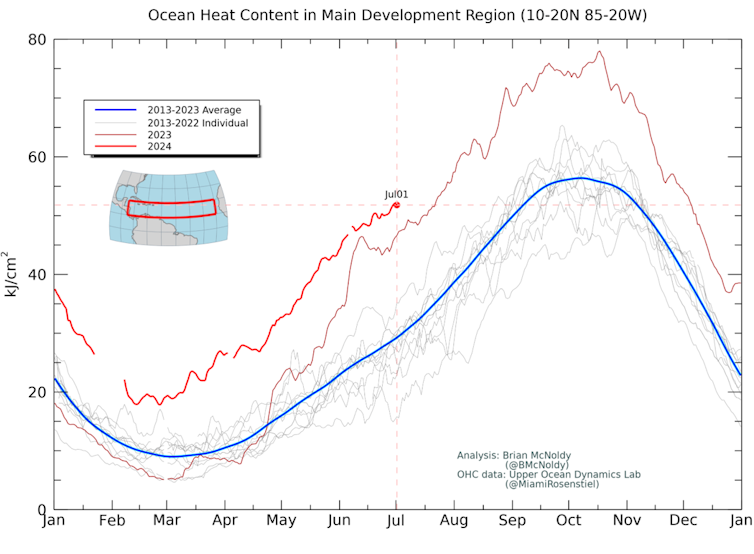

Scientists measure this reservoir of energy as ocean heat content. The ocean heat content leading up to Beryl was already extraordinarily high compared with past years. Normally, ocean heat content in the tropical Atlantic doesn't reach such high levels until early September, which is when hurricane season typically peaks in activity.

Ocean heat content of the Atlantic Ocean region where a large proportion of hurricanes form. The bold red line is 2024's ocean heat content, and the blue line is the 2013-2023 average. (Brian McNoldy/University of Miami)

Ocean heat content of the Atlantic Ocean region where a large proportion of hurricanes form. The bold red line is 2024's ocean heat content, and the blue line is the 2013-2023 average. (Brian McNoldy/University of Miami)Beryl is a storm more typical of the heart of hurricane season than of June, and its rapid intensification and strength have likely been driven by these unusually warm waters.

In addition to the high ocean heat content, research has shown other environmental factors need to typically align for rapid intensification to occur. These include:

Low vertical wind shear, where the winds steering the hurricane do not change much in strength or direction over the depth of the storm. Strong wind shear makes it difficult for a storm to stay organized and maintain its strength. A moist atmosphere surrounding the storm, with heavy precipitation encircling the developing eye.My research has shown that when this combination of factors is present, a hurricane can more efficiently take advantage of the energy it gathers from the ocean to power its winds, versus having to fight off drier, cooler air being injected from around the storm. The process is called ventilation.

Simultaneously, there is an increase in air being drawn inward toward the center, which quickly increases the strength of the vortex, similar to how a figure skater pulls their arms inward to gain spin. Rapid intensification is akin to a figure skater pulling in both their arms quickly and close to their body.

Has climate change affected the likelihood of rapid intensification?

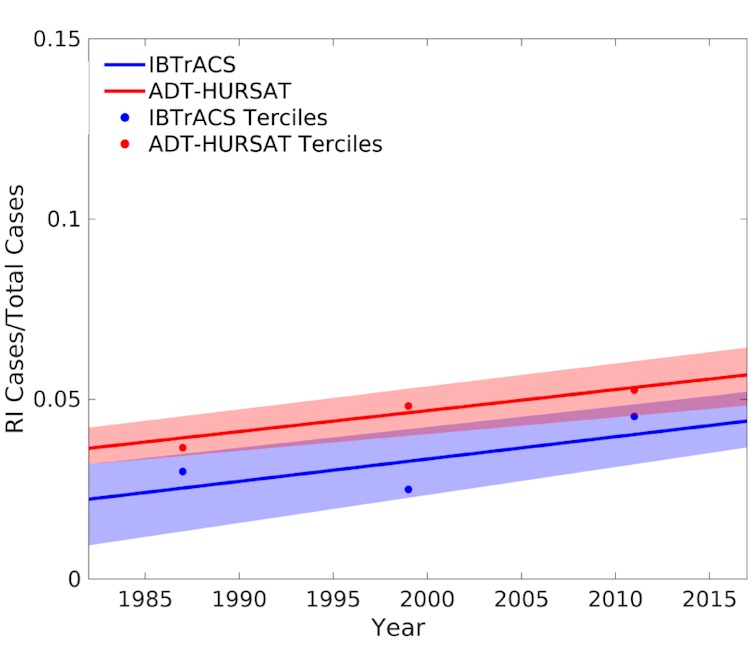

As oceans warm and ocean heat content gets higher with climate change, it is reasonable to hypothesize that rapid intensification might be becoming more common. Evidence does suggest that rapid intensification of storms has become more common in the Atlantic.

Additionally, the peak intensification rates of hurricanes have increased by an average of 25% to 30% when comparing hurricane data between 1971–1990 and 2001–2020. That has resulted in more rapid intensification events like Beryl.

This increase in rapid intensification is due to those environmental factors – warm waters, low vertical wind shear and a moist atmosphere – aligning more frequently and giving hurricanes more opportunity to rapidly intensify.

Two long-term datasets show an upward trend in the proportion of Atlantic hurricanes that rapidly intensified from 1982 to 2017. (Bhatia et al., 2022)

Two long-term datasets show an upward trend in the proportion of Atlantic hurricanes that rapidly intensified from 1982 to 2017. (Bhatia et al., 2022)The good news for anyone living in a region prone to hurricanes is that hurricane prediction models are getting better at forecasting rapid intensification in advance, so they can give residents and emergency managers more of a heads-up on potential threats.

NOAA's newest hurricane model, the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System, shows promise to further improve hurricane forecasts, and artificial intelligence could provide more tools to predict rapid intensification.

Brian Tang, Associate Professor of Atmospheric Science, University at Albany, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4 months ago

33

4 months ago

33