ARTICLE AD

Heist movies are seldom about solving climate change, and for a good reason. Nobody wants to hear a voice murmur from the back seat as George Clooney tears down the highway with a dump-truck full of stolen diamonds, "Hey, let's crush these sparkle-puppies into powder and scatter them through the stratosphere to cool the planet."

A team of researchers, led by climate scientist Sandro Vattioni from ETH Zurich in Switzerland, have done the math on which materials would be most suitable for a stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) method of global cooling, finding a few hundred trillion dollars' worth of diamond nanoparticles ought to do the trick.

Before you go on the lookout for a wise-cracking safe-cracker, a silent contortionist, and a wily femme fatale, nobody is suggesting SAI is the preferred means of avoiding future climate catastrophe. Not while there are safer, far cheaper options on the table like nixing fossil-fuel combustion.

Yet exercises like this study are worth having up our sleeve for a variety of reasons. They might actually help us avoid a worst-case scenario, or show us how to avoid a costly mistake. They could potentially even translate into studies on exotic exoplanet atmospheres far from Earth.

For decades, scientists have pondered whether silting the atmosphere with reflective particles could cast just enough shade to counter the warming effects of excess greenhouse gasses.

Of all the options, sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas has received a significant share of attention, largely because its dominant presence in a long history of volcanic emissions has provided researchers with plenty of natural experiments.

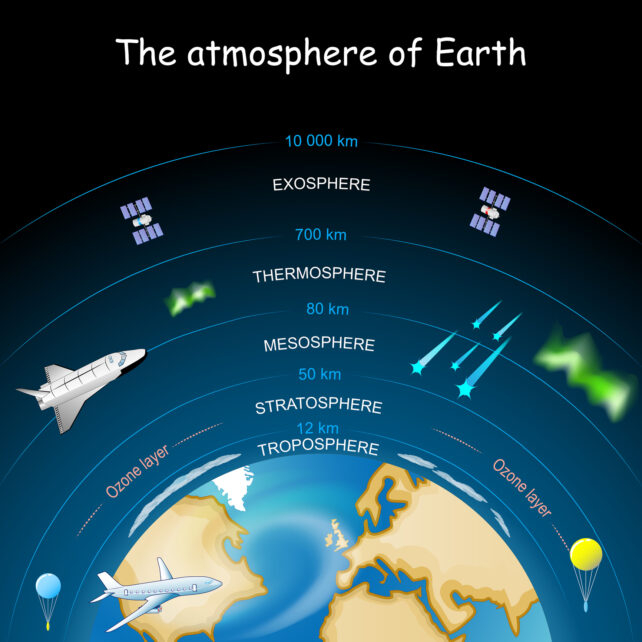

While dumping tens of millions of tonnes of the gas into the atmosphere would more than likely cut a couple of degrees from average global temperatures, we may not like the side effects. Ozone depletion, stratospheric warming, and a return of acid rain are just a few of the potential consequences we'd need to consider.

Now Vattioni and his team argue the physical qualities of sulfur particles might make them a poor choice of reflective material in the first place.

By incorporating the movements, thermodynamics, and chemistry of seven hypothetical aerosols in climate models, the researchers ranked the suitability of candidates in terms of heat absorption, reactivity, and reflectivity.

One major factor which isn't often considered, according to the researchers, is the tendency for particles to clump or settle while suspended in a fluid like the atmosphere. Particles that settle out too quickly may prove ineffective at scattering enough sunlight to cool the planet sufficiently. Those that clump too easily could trap heat, warming the stratosphere in ways that change air currents or capacity to hold moisture.

Layers of Earth's atmosphere. (ttsz/Getty Images)

Layers of Earth's atmosphere. (ttsz/Getty Images)Given a choice between two different kinds of titanium dioxide, alumina, calcite, diamond, silicon carbide, and sulfur dioxide, you couldn't beat injecting 5 million tons of 150 nanometer-wide bits of bling into the sky to achieve sufficient cooling.

Not only would each diamond particle stay airborne long enough to do a proper job, they wouldn't clump together, nor would they react to form toxic substances, the likes of which result in acid rain.

As for sulfur particles, the only material that fared worse was a form of titanium dioxide called rutile, which failed to provide any cooling benefits whatsoever.

The one thing SO2 has going for it is cost. At an estimated US$250 per megatonne, a sulfur-based aerosol is a far cheaper option than the US$600,000 per megatonne diamond dust would cost, especially when the total bill would quickly escalate into the tens or even hundreds of trillions.

Given the challenges in applying laboratory measurements and computer models to real world conditions, the study's predictions are far from guaranteed. If anything, the findings reinforce just how far we are from implementing SAI as a solution to global warming.

Which leaves one more seat in George Clooney's heist van for a femme fatale with a penchant for tiny diamonds.

This research was published in Geophysical Research Letters.

1 month ago

25

1 month ago

25