ARTICLE AD

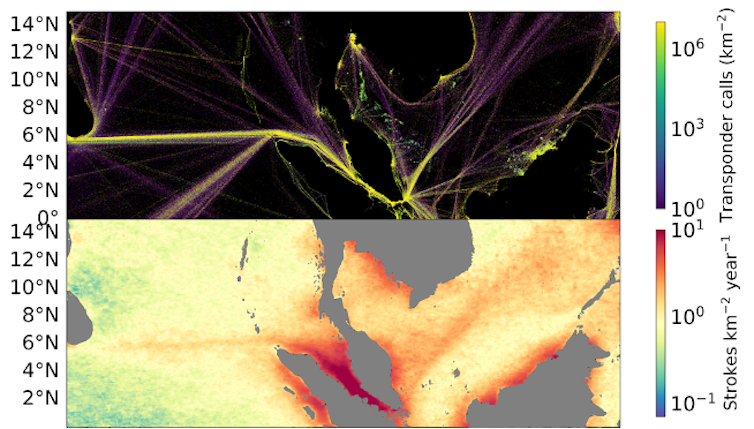

If you look at a map of lightning near the Port of Singapore, you'll notice an odd streak of intense lightning activity right over the busiest shipping lane in the world. As it turns out, the lightning really is responding to the ships, or rather the tiny particles they emit.

Using data from a global lightning detection network, my colleagues and I have been studying how exhaust plumes from ships are associated with an increase in the frequency of lightning.

For decades, ship emissions steadily rose as increasing global trade drove higher ship traffic. Then, in 2020, new international regulations cut ships' sulfur emissions by 77 percent.

Our newly published research shows how lightning over shipping lanes dropped by half almost overnight after the regulations went into effect.

Shipping lanes (top image) and lightning strikes (bottom) near the Port of Singapore. (Chris Wright)

Shipping lanes (top image) and lightning strikes (bottom) near the Port of Singapore. (Chris Wright)That unplanned experiment demonstrates how thunderstorms, which can be 10 miles tall, are sensitive to the emission of particles that are smaller than a grain of sand.

The responsiveness of lightning to human pollution helps us get closer to understanding a long-standing mystery: To what extent, if any, have human emissions influenced thunderstorms?

Aerosol particles can affect clouds?

Aerosol particles, also known as particulate matter, are everywhere. Some are kicked up by wind or produced from biological sources, such as tropical and boreal forests. Others are generated by human industrial activity, such as transportation, agricultural burning and manufacturing.

It's hard to imagine, but in a single liter of air – about the size of a water bottle – there are tens of thousands of tiny suspended clusters of liquid or solid. In a polluted city, there can be millions of particles per liter, mostly invisible to the naked eye.

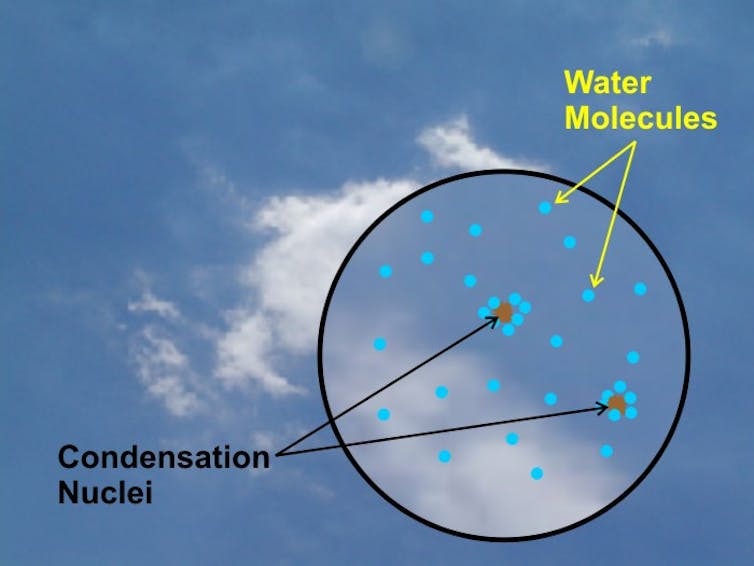

These particles are a key ingredient in cloud formation. They serve as seeds, or nuclei, for water vapor to condense into cloud droplets. The more aerosol particles, the more cloud droplets.

Water molecules condense around nuclei to form clouds. (David Babb/Penn State, CC BY-NC)

Water molecules condense around nuclei to form clouds. (David Babb/Penn State, CC BY-NC)In shallow clouds, such as the puffy-looking cumulus clouds you might see on a sunny day, having more seeds has the effect of making the cloud brighter, because the increase in droplet surface area scatters more light.

In storm clouds, however, those additional droplets freeze into ice crystals, making the effects of aerosol particles on storms tricky to pin down. The freezing of cloud droplets releases latent heat and causes ice to splinter.

That freezing, combined with the powerful thermodynamic instabilities that generate storms, produces a system that is very chaotic, making it difficult to isolate how any one factor is influencing them.

A view from the International Space Station shows the anvils of tropical thunderstorms as warm ocean air collides with the mountains of Sumatra. (NASA Visible Earth)

A view from the International Space Station shows the anvils of tropical thunderstorms as warm ocean air collides with the mountains of Sumatra. (NASA Visible Earth)We can't generate a thunderstorm in the lab. However, we can study the accidental experiment taking place in the busiest shipping corridor in the world.

Ship emissions and lightning

With engines that are often three stories tall and burn viscous fuel oil, ships traveling into and out of ports emit copious quantities of soot and sulfur particles.

The shipping lanes near the Port of Singapore are the most highly trafficked in the world – roughly 20 percent of the world's bunkering oil, used by ships, is purchased there.

In order to limit toxicity to people near ports, the International Maritime Organization – a United Nations agency that oversees shipping rules and security – began regulating sulfur emissions in 2020.

At the Port of Singapore, the sales of high-sulfur fuel plummeted, from nearly 100 percent of ship fuel before the regulation to 25 percent after, replaced by low-sulfur fuels.

But what do shipping emissions have to do with lightning?

Scientists have proposed a number of hypotheses to explain the correlation between lightning and pollution, all of which revolve around the crux of electrifying a cloud: collisions between snowflake-like ice crystals and denser chunks of ice.

When the charged, lightweight ice crystals are lofted as the denser ice falls, the cloud becomes a giant capacitor, building electrical energy as the ice crystals bump past each other. Eventually, that capacitor discharges, and out shoots a lightning bolt, five times hotter than the surface of the Sun.

We think that, somehow, the aerosol particles from the ships' smokestacks are generating more ice crystals or more frequent collisions in the clouds.

In our latest study, my colleagues and I describe how lightning over the shipping lane fell by about 50 percent after 2020. There were no other factors, such as El Niño influences or changes in thunderstorm frequency, that could explain the sudden drop in lightning activity. We concluded that the lightning activity had fallen because of the regulation.

The reduction of sulfur in ship fuels meant fewer seeds for water droplet condensation and, as a result, fewer charging collisions between ice crystals. Ultimately, there have been fewer storms that are sufficiently electrified to produce a lightning stroke.

What's next?

Less lightning doesn't necessarily mean less rain or fewer storms.

There is still much to learn about how humans have changed storms and how we might change them in the future, intentionally or not.

Do aerosol particles actually invigorate storms in general, creating more extensive, violent vertical motion? Or are the effects of aerosols specific to the idiosyncrasies of lightning generation? Have humans altered lightning frequency globally?

My colleagues and I are working to answer these questions. We hope that by understanding the effects of aerosol particles on lightning, thunderstorm precipitation and cloud development, we can better predict how the Earth's climate will respond as human emissions continue to fluctuate.![]()

Chris Wright, Fellow in Atmospheric Science, Program on Climate Change, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

7 hours ago

4

7 hours ago

4