ARTICLE AD

Could a long-lost moon explain the rather unusual shape of Mars, as well as the terrain on the planet's surface? It's an intriguing hypothesis put forward in a new paper by astronomer Michael Efroimsky from the US Naval Observatory in Washington DC.

To a greater degree than any other planet in the Solar System, Mars has a starkly triaxial shape: an ellipsoid with significant differences in curve along all three of its axes. In other words, it's squished in ways that have previously puzzled experts.

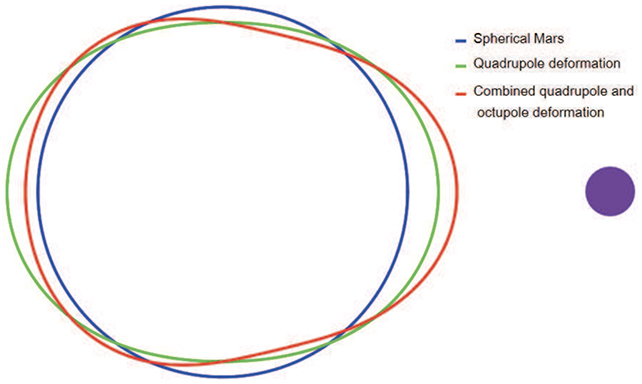

How Nerio might have affected the shape of Mars. (Efroimsky, 2024)

How Nerio might have affected the shape of Mars. (Efroimsky, 2024)A third Martian moon around a third the size of our own could explain the anomaly. Mars's current satellites Phobos and Deimos may even be the shattered remains of this object following destruction during the cataclysmic period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment some 4 billion years ago.

"We christen the hypothetical moon Nerio, after a war goddess who was Mars' partner in ancient cult practices, later to be supplanted by deities adapted from other religions," writes Efroimsky.

As per Efroimsky's calculations and modeling, the gravitational pull of the hypothesized mass would have been enough to elongate Mars before its shape became fixed, potentially pulling ancient magma oceans to and fro.

"An initial, 'seed' triaxiality was created by a massive moon orbiting a young and still plastic Mars on a synchronous orbit," writes Efroimsky in his paper. "Showing the same face to the moon, Mars assumed a shape close but not identical to a triaxial ellipsoid, its longest axis aligned with the moon."

The presence of Nerio could also explain some of the topographical features on Mars: Compared to the rest of the Solar System, the red planet has the most prominant highlands (Tharis), the biggest canyon (Valles Marineris), and the joint-tallest mountain (Olympus Mons).

These bulges could be explained by Nerio, argues Efroimsky. A large moon in the early days of Mars would have also triggered more volcanic activity, potentially leading to some of the notable features we see on the surface of the planet today.

"After the moon produced the seed triaxiality and asymmetry of Mars, the tidally elevated provinces became, more than others, prone to convection-generated uplifts and tectonic and volcanic activity," writes Efroimsky.

A lost moon hypothesis still leaves plenty of questions unanswered – there's no evidence of a moon of Nerio's size colliding with Mars, for example – but further studies should shed more light on whether or not this moon ever did exist.

It may have drifted out of orbit, of course, or been completely destroyed, with the only signs of its brief existence being the misshapen shape of our dusty red neighbor.

The research has been submitted for inclusion in Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, and is available on the pre-print server arXiv.org.

2 months ago

22

2 months ago

22