ARTICLE AD

A new 'laser-powered' project being launched in the state of Western Australia could revolutionize global communications.

Two optical ground stations in a strategically placed network have successfully received laser signals from a German satellite, researchers say, paving the way to increase the capacity of space-to-Earth communications by a staggering 1,000 times.

The 'TeraNet' initiative is led by astrophotonics scientist Sascha Schediwy from the University of Western Australia (WA) and funded by the Australian Space Agency's Moon to Mars Demonstrator Mission.

"The overall aim of the project is to contribute towards Australia's vision for the next generation of space exploration," Schediwy told ScienceAlert.

Since the launch of Spuntik I in 1957, satellites have communicated via radio waves. Their low-frequency signal limits their capacity to transmit data, and after nearly 70 years of development, radio-wave communications are becoming unable to keep up with the enormous demand for data transfer.

"It's been pushed to the absolute extreme, but it's really now reached a bottleneck," said Schediwy.

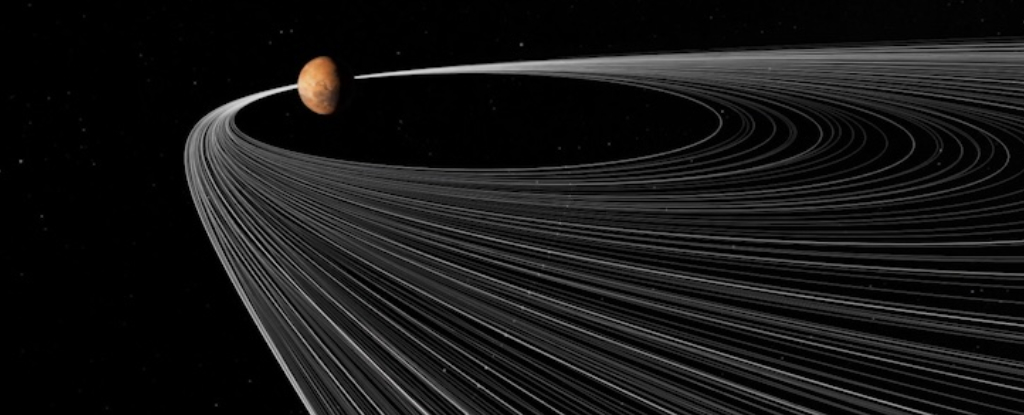

With thousands of satellites orbiting Earth, there's a huge volume of data being collected that needs to be sent back down. High-frequency laser communications could present a solution.

"By switching to infrared laser beams for communications, we get a factor of 100, or 1,000, times greater bandwidth," said Schediwy.

Among its many potential applications, the researchers hope this powerful satellite communications system will help people feel more connected to space exploration than ever before.

"We can have multiple camera angles and 4K video footage of the next people landing on the Moon," Schediwy said. "That's a really exciting aspect of the technology, I think."

Traditional radio communications tend to have a wide broadcast area, which can cause overlap and interference between radio signals. The short-wavelength signals being used by TeraNet will be more focused.

"With optical signals, instead of your beam being maybe 100 kilometers [62 miles] across, it can be 100 meters [328 ft] across. So, you're really targeting an individual user on the ground," said Schediwy.

With such distinct advantages on offer, it could seem surprising that optical communications haven't been more widely adopted. But these laser-powered systems have a drawback.

Unlike their radio-wave counterparts, targeted short-wavelength signals are prone to interference. Lasers are easily interrupted by clouds, making them an unreliable option for satellite communications.

The team has a surprisingly simple solution. The system will have ground stations at several locations in WA connected to the same network, so hopefully, at least one station will always have a clear connection with the satellite.

"If it is cloudy in Perth, the satellite can download its data up at Mingenew, 300 kilometers [186 miles] north," said Schediwy.

If the Perth and Mingenew stations are both blocked by cloud, the TeraNet program has a final ace up its sleeve: an additional ground station receiver mounted on the back of a Jeep that can be driven out to whatever coordinates are necessary to achieve the best signal.

If this initial three-station network is successful, the team is already looking to collaborate with other organizations on the east coast of Australia and in New Zealand to set up an Australasian optical ground station network, and that's only the beginning.

"WA is geographically ideally located to be part of a global communications infrastructure, with an oversight of a large part of the Indian Ocean and a reach into Southeast Asia and the polar region," Schediwy told ScienceAlert.

Once established, a global optical communications network will enable continuous, ultra-fast satellite data downloads. This could transform situations requiring the rapid sharing of large amounts of data, such as disaster response.

It might only be three ground stations right now, but it will potentially herald a new space age of communication.

"This demonstration is the critical first step," says Schediwy.

3 months ago

37

3 months ago

37