ARTICLE AD

Scientists have discovered a naturally-occurring molecule that aids appetite control and weight loss so well, it may compete with popular GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic.

It's called BRP (BRINP2-related peptide), and works by activating particular neurons in the brain in a similar way to GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) agonists. The difference between the two peptides is the metabolic route each takes to get there.

Pathology researcher Laetitia Coassolo from Stanford University led a team to design an AI-based drug discovery program called 'Peptide Predictor', which they used to identify 373 proteins for further investigation among thousands of possibilities. From this haystack they screened 100 peptides that might induce the kind of brain activity needed to meddle with appetite.

One of these was the tiny BRP molecule, made up of just 12 amino acids.

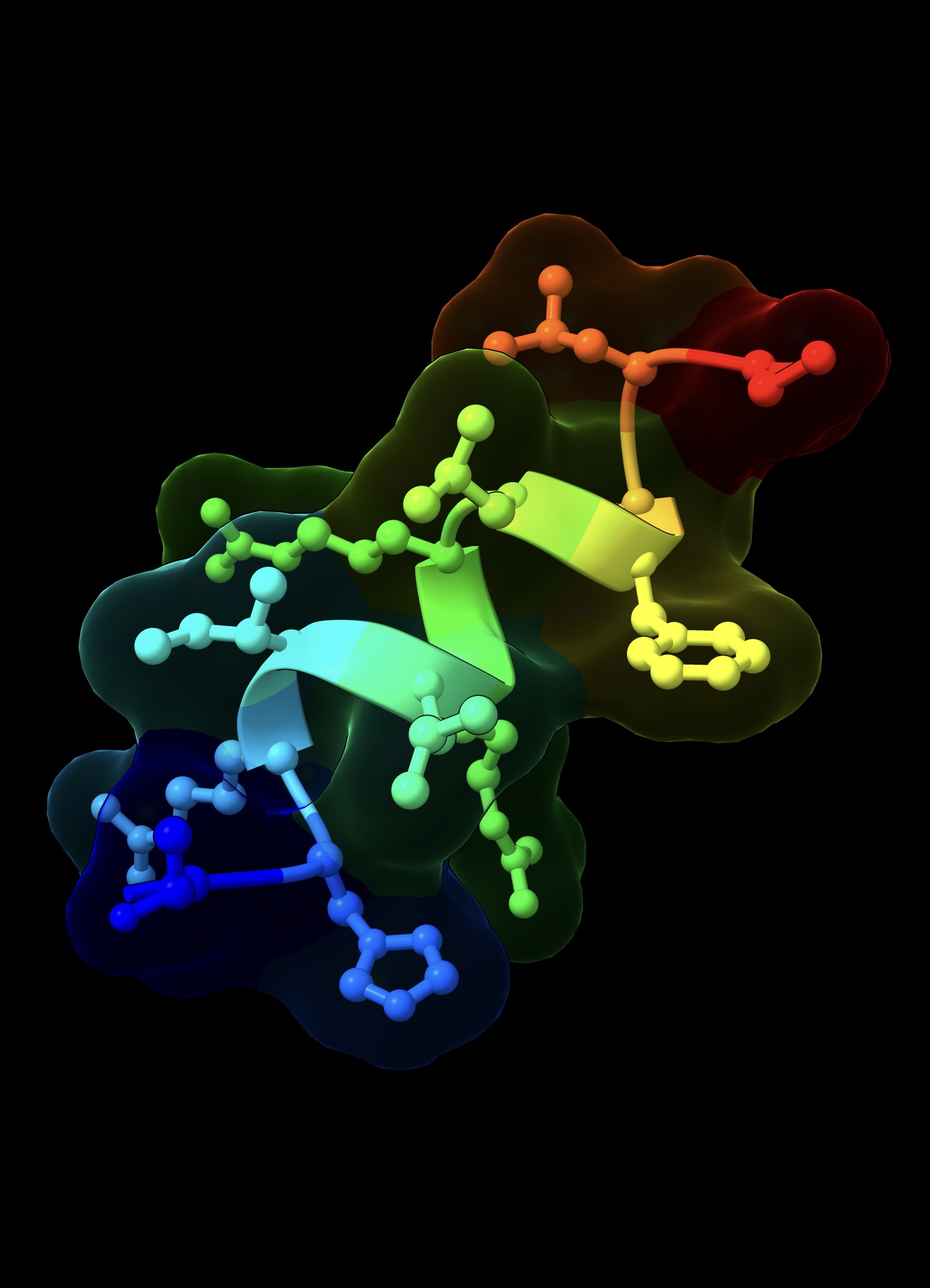

The 12-amino-acid BRP peptide (spheres are atoms and sticks are bonds) suppresses appetite and reduces weight gain in mice and pigs without causing nausea or food aversion. (Katrin Svensson/Stanford Medicine)

The 12-amino-acid BRP peptide (spheres are atoms and sticks are bonds) suppresses appetite and reduces weight gain in mice and pigs without causing nausea or food aversion. (Katrin Svensson/Stanford Medicine)In the lab, the GLP-1 peptide increased markers of activity in human insulin cells by a factor of three, while a growth factor increased similar activity by a factor of 10 in brain cells.

By comparison, BRP raised markers of activity in both neuronal and insulin-producing cells more than tenfold.

Animal testing in lean, male mice revealed that injecting BRP could halve the amount of food they ate in the hour that followed. It had the same effect on minipigs, whose metabolisms and eating behaviors are more similar to humans.

When obese mice were given these BRP injections across 14 days, they lost an average of 4 grams compared to controls. And almost all of that weight loss was from body fat, not muscle.

Semaglutide treatments can trigger not only loss of fat, but of muscle and bone, which may account for as much as 20 percent of the weight lost. This has raised questions about the long-term impacts of taking drugs like Ozempic for weight loss, which will only come to light in time. Further research is needed to determine whether, for instance, heart health may suffer.

GLP-1 agonists can also come with other unpleasant side effects, like nausea and constipation. Meanwhile, animal testing of BRP showed no sign of these side-effects, or muscle loss, perhaps because the molecule activates different brain receptors.

"The receptors targeted by semaglutide are found in the brain but also in the gut, pancreas, and other tissues," says Stanford pathology researcher Katrin Svensson.

"That's why Ozempic has widespread effects including slowing the movement of food through the digestive tract and lowering blood sugar levels."

BRP, on the other hand, appears to work in the hypothalamus, the brain's appetite and metabolism center, activating entirely different metabolic and neuronal pathways to semaglutide.

Whether it will make it to market will depend on how the molecule performs in the human body, which Svensson's company will soon investigate in clinical trials.

There's a lot of money to be made in developing drugs to treat obesity, and the market is only expected to increase: scientists predict four in every five Americans will be obese or overweight by 2050.

If it proves safe and effective, BRP will be stepping into an increasingly crowded ring of peptide-based weight loss drugs, alongside Ozempic, Wegovy, and Tirzepatide.

"The lack of effective drugs to treat obesity in humans has been a problem for decades," Svensson says.

"Nothing we've tested before has compared to semaglutide's ability to decrease appetite and body weight. We are very eager to learn if [BRP] is safe and effective in humans."

This research was published in Nature.

17 hours ago

8

17 hours ago

8