ARTICLE AD

Repeated sightings of an elusive whale in a strange place could indicate a cultural tradition.

Scientists have repeatedly seen a group of Baird's beaked whales (Berardius bairdii) frolicking in shallow waters around the Commander Islands, at the border between the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. The strange part? Baird's beaked whales, like all beaked whales, are a deep-sea species.

Yet, between 2008 and 2019, a team led by marine scientist Olga Filatova and Ivan Fedutin of the University of Southern Denmark saw the group of whales appear every single year, in waters shallower than just 300 meters (984 feet).

"It is uncharacteristic for this species," Filatova says, in what might be something of an understatement.

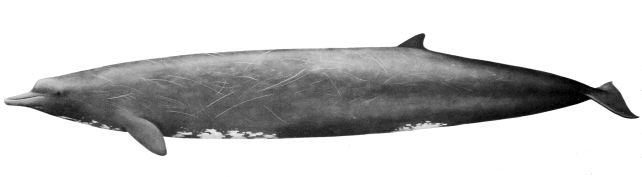

Baird's beaked whales reach nearly 13 meters (43 feet) in length. (NOAA)

Baird's beaked whales reach nearly 13 meters (43 feet) in length. (NOAA)Beaked whales are among the most mysterious and elusive of all the different cetaceans that populate our oceans. They tend to live in some of the most inhospitable environments to humans on the planet, and dive deep: Baird's beaked whales plunge as deep as 3,000 meters in their search for prey, well into the cold dark waters of the bathypelagic.

It's for these reasons that the whales are sighted rarely and are not well-studied: they simply live their lives in a way that is largely incompatible with humans poking around. Then, in 2008, Filanova and Fedutin made the sighting near the Commander Islands that would dramatically alter our understanding of these enigmatic creatures.

"We were there to look for killer whales and humpback whales, so we just noted that we had seen a group of Baird's beaked whales and didn't do much about it," Filatova recalls. "But we also saw them in the following years, and after five years, we suspected that it was a stable community frequently visiting the same area."

They began to pay closer attention, documenting where they saw the whales, how many, and whether or not the same whales were visiting the spot every year. They documented a total of 186 individual whales over the 12-year span.

That population consisted of a core group of 79 whales that were seen over two or more years, returning to the place repeatedly. Those whales, the researchers classified as the resident pod. The remaining 107 individuals were only seen once; those were the transient group.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" allowfullscreen>

Some of the transients just came and went, but 61 transients were seen interacting with the resident group; and seven of them were seen in the shallow water thought to be so foreign to the species.

This, the team says, seems indicative of the development and sharing of cultural traditions.

"The transients are not as familiar with local conditions as the residents, and therefore, they usually seek food at the depths that are normal for their species," Filatova says.

"But we actually observed some transients in the shallow area. These were individuals who had some form of social contact with the residents. It must be in that contact that they learned about the shallow water and its advantages."

The researchers believe that, as observed with other animals, including cetaceans, the transient whales learn about the benefits of the location by observing, interacting with, and copying the resident population. This type of cultural sharing is also observed in animals such as orcas, which have been spotted engaging in social fads.

Orcas, dolphins, and other whales also share hunting techniques for different types of prey, for instance. They find a new way to do something, or access food, and other individuals pick it up and copy it until it is shared among a group.

"It becomes a cultural tradition, and it is the first time a cultural tradition has been observed among beaked whales," says Filatova.

Baird's beaked whales breaching near the Commander Islands. (Olga Filatova/University of Southern Denmark)

Baird's beaked whales breaching near the Commander Islands. (Olga Filatova/University of Southern Denmark)While it is not perhaps surprising that cetaceans exhibit complex cultural behaviors, it does suggest that predicting the behavior of these animals is not as simple as we thought. And this has implications for trying to protect them in a rapidly and dramatically changing world.

"It means that you cannot expect all individuals within a specific species to behave the same way," Filatova explains. "This makes it difficult to plan species protection – in this case, for example, you cannot plan based on the assumption that beaked whales only live far out in deep sea. We have shown that they can also live in shallow and coastal waters. There may be other different habitats that we are not aware of yet."

The team's research has been published in Animal Behaviour.

1 year ago

82

1 year ago

82