ARTICLE AD

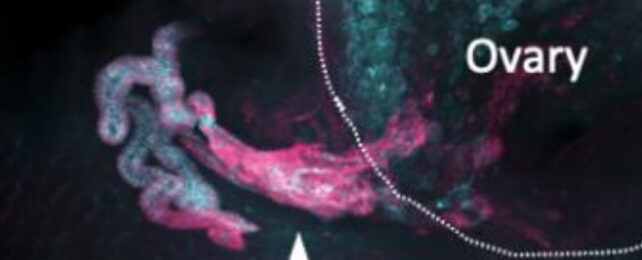

Fluorescently died component of the external part of the rete overaii extending out from the ovaries. (Anbarci, bioRxiv, 2024)

Fluorescently died component of the external part of the rete overaii extending out from the ovaries. (Anbarci, bioRxiv, 2024)

While diligently recorded in early versions of the famous surgical reference book, Gray's Anatomy, the rete ovarii's existence has largely fallen into obscurity, left out of modern texts and dismissed as a "functionless vestige".

This is despite the fact the structure is highly conserved across mammal species, from camels to guinea pigs, suggesting the small ovarian structure has an important enough role.

What's more, an equivalent (if simpler) structure in males – the rete testis – has a known function involved in maintaining the fluid in the testicles and helps with sperm transport.

Far from the first female reproductive structure to have been overlooked, dismissal of the rete ovarii is now finally being corrected thanks to Duke University cell biologist Dilara Anbarci and colleagues, who are now using modern techniques to examine this ovary accessory in mice.

"We think it is regulating the timing or rate of ovulation," Duke University developmental biologist Blanche Capel told Michael Le Page at New Scientist.

"It may control how many [ovarian] follicles are activated in one's cycle or when they are activated. So we could perhaps use it somehow to extend the female reproductive lifespan."

By injecting mice rete overii with fluorescent dye, the researchers confirmed its contents flow towards the ovaries. The tissue's secretions include at least 15 proteins with yet to be established purposes.

A dense tangle of blood vessels surrounds the structure, which is also directly connected to a system of neurons that join to muscle cells for contraction like they do in the uterus or to the outer cell layer like they do in our gut.

Together these anatomical features suggest the tiny structure may contribute to hormone signaling, which could control how many follicles on an ovary produce eggs each cycle. The rete ovarii may be a sensory appendage and act like the ovary's 'tongue'.

In flies and worms, ovaries respond to changing conditions in their immediate environment, including those induced by changes in diet. Anbarci and team suspect this may be the rete ovarii's role, to sense changes in the immediate environments of mammalian ovaries' and send signals for their reproductive organs to respond accordingly.

"The direct proximity of the rete ovarii to the ovary and its integration with the extraovarian landscape suggest that it plays an important role in ovary development and homeostasis," the researchers write in their paper.

There's still much to confirm but the researchers next intend to challenge this structure's response to physiological signals including hormones and diet changes.

"We suggest that the RO be added to this list and investigated as an additional component of female reproductive function," the researchers conclude.

This research has been uploaded to bioRxiv and has yet to be peer reviewed.

11 months ago

58

11 months ago

58