ARTICLE AD

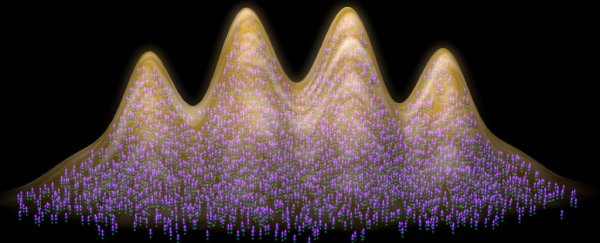

Researchers had previously managed to observe crystal structures inside supersolids in several ways. (University of Innsbruck)

Researchers had previously managed to observe crystal structures inside supersolids in several ways. (University of Innsbruck)

Scientists on Wednesday said that they have successfully stirred a strange matter called a "supersolid" – which is both rigid and fluid – for the first time, providing direct proof of the dual nature of this quantum oddity.

In everyday life, there are four states of matter – solid, liquid, gas, and the rarer plasma.

But physicists have long been investigating what are known as "exotic" states of matter, which are created at incredibly high energy levels or temperatures so cold they approach absolute zero (-273.15 degrees Celsius or -459.67 degrees Fahrenheit).

Under these extreme conditions, matter starts behaving very differently from what we are used to.

Fluids such as liquid or gas may get more or less resistance to flow, which is measured by viscosity. Honey, for example, is more viscous than water.

Superfluids, an extremely cold exotic matter, have zero viscosity – there is no resistance so they flow freely.

If a superfluid was stirred in a cup, it would flow around indefinitely without ever slowing down.

More than half a century ago, physicists predicted the existence of a "supersolid" state.

It is matter that has the properties of both a solid and a superfluid, in which a fraction of the atoms flow friction-free through the lattice – a regular arrangement of points or objects – of a rigid crystal structure.

'Like holes in Gruyere cheese'

Researchers had previously managed to observe these crystal structures inside supersolids in several ways.

But a direct observation of the bizarre manner in which this matter flows has remained elusive, said Francesca Ferlaino, a physicist at Austria's University of Innsbruck.

Until a new study led by Ferlaino was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

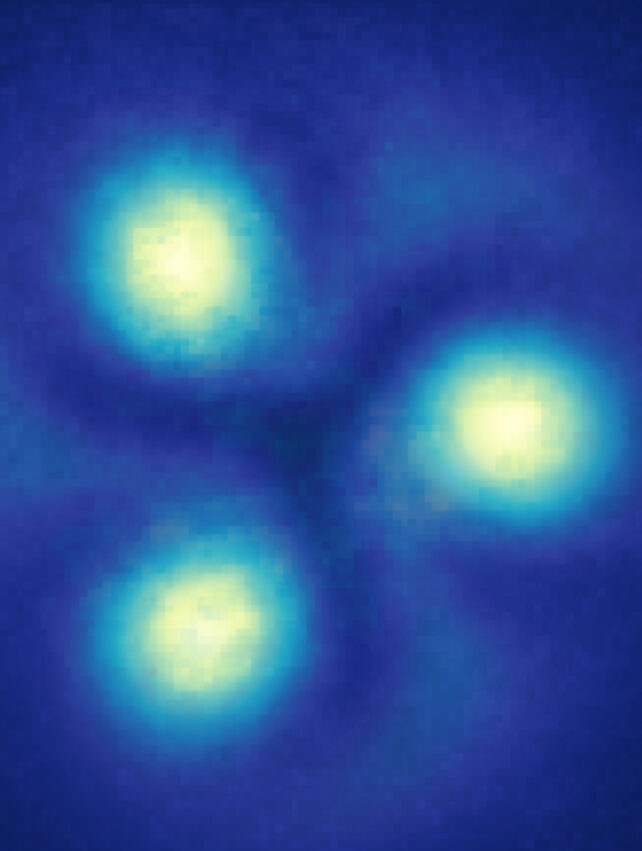

The team managed to stir a supersolid to observe the tiny whirlpools – called quantized vortices – which are the "smoking gun of superfluidity", Ferlaino told AFP.

"Imagine you have a cup of coffee, and you give it a little swirl with a spoon," she explained.

"You'll see the coffee spinning around the center, and if you look closely, there might be a whirlpool in the middle where the liquid is swirling the fastest. This is a classic example of a vortex in a regular fluid."

Now imagine the coffee is replaced with a superfluid.

"If you swirl the spoon slowly, you'll be surprised to see that the superfluid doesn't rotate along with the spoon at all – it remains perfectly still, as if nothing disturbed it," Ferlaino said.

"However, if you swirl the spoon faster, instead of forming one large whirlpool in the center, something remarkable happens. A series of tiny whirlpools, or quantised vortices, begin to appear," she said.

"These are like small holes in the fluid, each rotating at a specific speed," she explained.

"Instead, they arrange themselves in beautiful, regular patterns across the surface of the superfluid, almost like the holes in a piece of Gruyere cheese, but perfectly organized."

Simulation of quantum vortices superimposed with experimental data. (University of Innsbruck)

Simulation of quantum vortices superimposed with experimental data. (University of Innsbruck)Exploding stars

In 2021, the Innsbruck University team created a long-lived, two-dimensional supersolid by cooling particular atoms and molecules to extremely low temperatures in the lab.

"The next step – developing a way to stir the supersolid without destroying its fragile state – required even greater precision," lead study author Eva Casotti said.

The team used magnetic fields to carefully rotate their supersolid, stirring it up to create the pretty quantized vortices.

"Our findings give us strong, direct proof of the dual nature of a supersolid state," Ferlaino said.

The researchers say the breakthrough will make it possible to simulate phenomena in the lab that normally only occur under truly extreme conditions.

This includes what happens at the heart of neutron stars, the incredibly dense and compact cores left behind when massive stars go supernova.

"It is assumed that the change in rotational speed observed in neutron stars – so-called glitches – are caused by superfluid vortices trapped inside neutron stars," Thomas Bland, who worked on the project, said in a statement.

2 weeks ago

16

2 weeks ago

16