ARTICLE AD

There are limits to what we can see across the gulf of space and time separating us from the early Universe. Light that travels across billions of light-years emanates from sources so distant it can be challenging even to see something even as luminous as a galaxy glowing in the darkness.

Human endeavor has now smashed through those limits using JWST – resolving more than 40 individual stars on the outskirts of a galaxy whose light has spent almost 6.5 billion years traversing space-time to reach us.

"This groundbreaking discovery demonstrates, for the first time, that studying large numbers of individual stars in a distant galaxy is possible," says astrophysicist Fengwu Sun from the University of Arizona.

"While previous studies with the Hubble Space Telescope found around seven stars, we now have the capability to resolve stars that were previously outside of our capability. Importantly, observing more individual stars will also help us better understand dark matter in the lensing plane of these galaxies and stars, which we couldn't do with only the handful of individual stars observed previously."

Although stars from distant galaxies are usually too small to see individually, we do see the occasional outlier, thanks to a quirk of space-time described by general relativity.

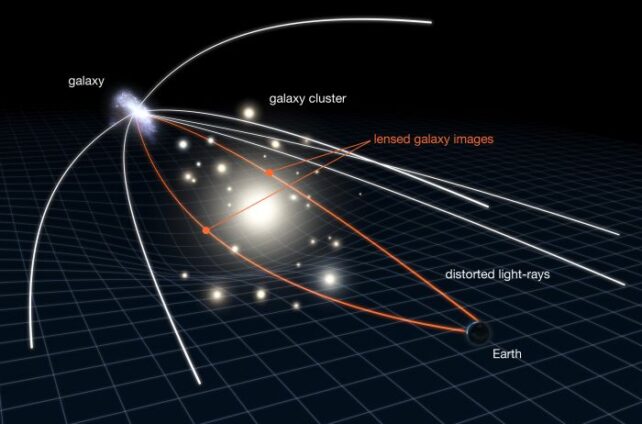

Around sufficiently large masses with strong gravitational fields, space-time itself curves and warps – like the mat of a trampoline warps under a bowling ball. Any light that travels through this warped space-time can become distorted, replicated, and magnified, an effect known as gravitational lensing.

Diagram illustrating gravitational lensing. (NASA, ESA & L. Calçada)

Diagram illustrating gravitational lensing. (NASA, ESA & L. Calçada)The Dragon Arc is a smear of light across the sky that resembles a Chinese dragon, with separate images of the same distant spiral galaxy making up its head and tail.

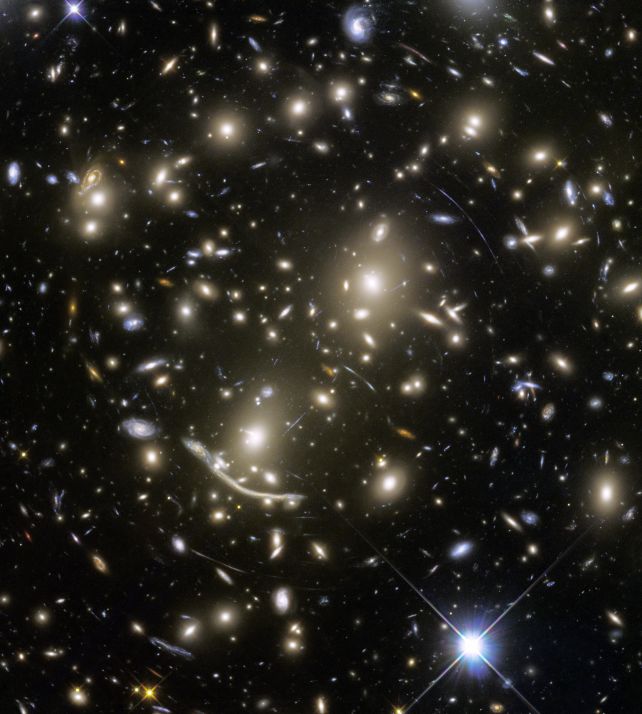

The illusion is caused by the gravitational warping of space surrounding a massive cluster of galaxies called Abell 370, located just 4 billion light-years away. Although the more distant light comes to us as a bit of a jumbled mess, astronomers are able to reverse-engineer the gravitational lensing process to see the background galaxies as they would have looked without the smearing – with the added bonus of magnification.

But that's not all. In the space between the galaxies in the Abell 370 cluster, a number of isolated stars drift around, alone. Each star is capable of adding an additional lensing effect of its own, a phenomenon known as microlensing.

Gravitational lenses have been used previously to resolve individual stars in the distant Universe. Using the microlensing of rogue intracluster stars, a team led by astronomer Yoshinobu Fudamoto of Chiba University in Japan was able to resolve an unprecedented 44 individual stars in the smeared light of the Dragon Arc.

A Hubble deep image of Abell 370. (NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz and the HFF Team/STScI)

A Hubble deep image of Abell 370. (NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz and the HFF Team/STScI)"When we discovered these individual stars, we were actually looking for a background galaxy that is lensing-magnified by the galaxies in this massive cluster," Sun says.

"But when we processed the data, we realized that there were what appeared to be a lot of individual star points. It was an exciting find because it was the first time we were able to see so many individual stars so far away."

Armed with this information, the team found that many of the stars in the Dragon Arc are red supergiants – massive, red stars at the end of their lifespans that have puffed up as their fuel runs low. These are cooler, redder stars than those typically resolved across vast intergalactic distances, which tend to be large, bright, hot blue and white giants.

This information tells us just a little bit more about the evolution of galaxies very far from our own. Because red supergiant stars are cooler, they tend to be more difficult to see than the hot ones. JWST's ability to see red light has given it an edge in finding objects outside the range of other instruments.

Further JWST observations are expected to reveal even more stars hiding in the blurry light of the Dragon Arc, billions of light-years away.

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.

18 hours ago

12

18 hours ago

12