ARTICLE AD

Scientists at Cornell University have created mini virtual reality headsets for mice. These MouseGoggles aren't just to help the critters unwind after a long day in the lab; they offer researchers a glimpse into their behavior and brain functions.

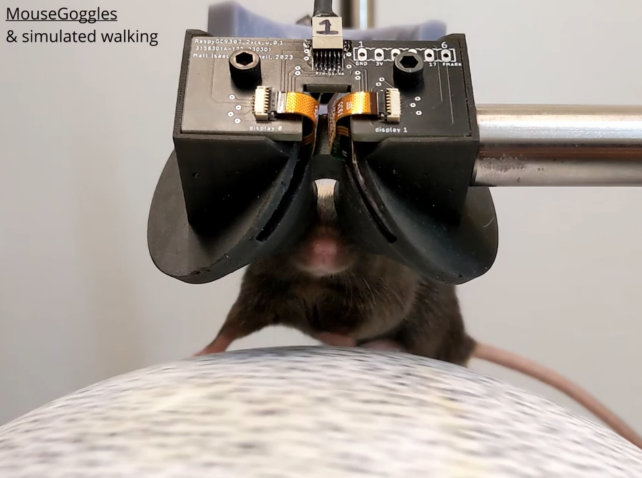

A mouse wearing a tiny VR headset is an adorable mental image, but the set does lack the mobility of our own face-mounted goggles. Instead, MouseGoggles are held in place on a scaffold, sporting two smartwatch displays behind a pair of Fresnel lenses, complete with tech that tracks the animals' eye movements and pupil dilation.

The mice quickly learned to navigate their virtual environment by running on a spherical treadmill. And those visuals appeared to be more immersive than ever – seen through MouseGoggles, the mice reacted to reward and fear stimuli far more strongly than when viewing virtual worlds on big 360-degree projector screens.

It's not all fun and games, though. By making VR more realistic for mice, scientists can more precisely monitor the brain activity associated with spatial navigation and memory.

If you've ever strapped on a VR headset, you'll know that it feels more immersive than watching something on a big screen. According to the new Cornell study, it seems even mice feel that way.

Earlier attempts at testing the animals in virtual environments involved placing them in the center of circular screens, with visuals projected on the walls. While the mice did learn to navigate by running on a spherical treadmill, the stuff they were seeing was apparently less convincing.

A mouse runs on a spherical treadmill to move around in the virtual world. (Isaacson et al., Nature Methods, 2024/CC BY 4.0)

A mouse runs on a spherical treadmill to move around in the virtual world. (Isaacson et al., Nature Methods, 2024/CC BY 4.0)The researchers tested mice in MouseGoggles and traditional screen-based VR systems with a 'looming stimulus.'

A dark blob quickly expanded in their field of view, simulating an approaching predator. The mice would not only jump and arch their backs but also slow their walking speed, shift their gaze, and dilate their pupils.

"When we tried this kind of a test in the typical VR setup with big screens, the mice did not react at all," says neuroscientist Matthew Isaacson, lead author of the study.

"But almost every single mouse, the first time they see it with the goggles, they jump. They have a huge startle reaction. They really did seem to think they were getting attacked by a looming predator."

In experiments that were more pleasant for the subjects, the team trained mice on a looped linear VR track where they were given liquid rewards for licking at a certain spot. On the fourth or fifth day, they were given no reward – yet they still licked in the same location in anticipation of a treat, and slowed their 'exploratory licking' outside the reward zones.

These results indicated that the MouseGoggles setup could still allow for spatial learning in mice.

The ultimate goal isn't just to provide better VR gaming experiences – more accurate simulations mean scientists can test the neurological responses of mice in a wider variety of situations than otherwise possible in the lab. As the looming experiments show, projection-based VR just isn't believable enough for the mice.

"The more immersive we can make that behavioral task, the more naturalistic of a brain function we're going to be studying," says biomedical engineer Chris Schaffer.

The MouseGoogles design is cheaper too, and allows for extra features like eye tracking.

The next steps, according to the team, are to develop wearable versions for other animals, and even integrate other senses into the experience.

"I think five-sense virtual reality for mice is a direction to go for experiments, where we're trying to understand these really complicated behaviors, where mice are integrating sensory information, comparing the opportunity with internal motivational states, like the need for rest and food, and then making decisions about how to behave," says Schaffer.

The research was published in the journal Nature Methods.

1 day ago

25

1 day ago

25