ARTICLE AD

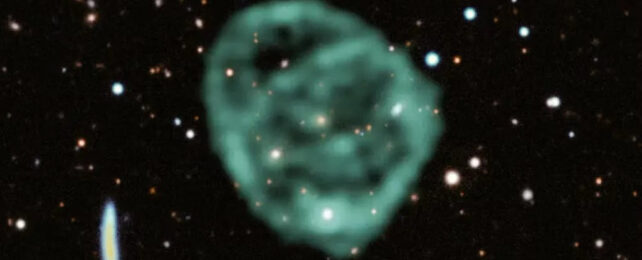

Image of the first odd radio circle ever discovered, with radio observations (green) on top of an optical and infrared map. (U. Manitoba/EMU/MeerKAT/DES/CTIO)

Image of the first odd radio circle ever discovered, with radio observations (green) on top of an optical and infrared map. (U. Manitoba/EMU/MeerKAT/DES/CTIO)

Within the last five years, astronomers have discovered a new type of astronomical phenomenon that exists on vast scales – larger than whole galaxies. They're called ORCs (odd radio circles), and they look like giant rings of radio waves expanding outwards like a shockwave.

Until now, ORCs had never been observed in any wavelength other than radio, but according to a new paper released on April 30 2024, astronomers have captured X-rays associated with an ORC for the first time.

The discovery offers some new clues as to what might be behind the creation of an ORC.

While many astronomical events, like supernova explosions, can leave behind circular remnants, ORCs seem to require a different explanation.

"The power needed to produce such an expansive radio emission is very strong," said Esra Bulbul, lead author of the new paper. "Some simulations can reproduce their shapes but not their intensity. No simulations explain how to create ORCs."

ORCs can be a challenge to study, in part because they are usually only visible in radio wavelengths. They haven't previously been associated with X-ray or infrared emissions, nor has there been any sign of them in optical wavelengths.

Sometimes, ORCs surround a visible galaxy, but not always (eight have been discovered to date around known elliptical galaxies).

Using ESA's XMM-Newton telescope, Bulbul and her team observed one of the nearest known ORCs, an object called the Cloverleaf, and found a striking X-ray component to the object.

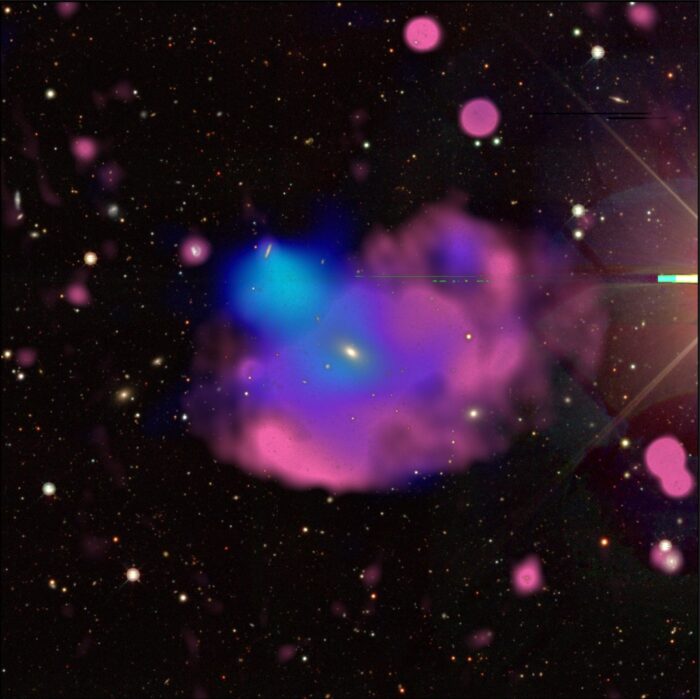

This multiwavelength image of the Cloverleaf ORC (odd radio circle) combines visible light observations from the DESI ( Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument) Legacy Survey in white and yellow, X-rays from XMM-Newton in blue, and radio from ASKAP (the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder) in red. (X. Zhang and M. Kluge/MPE/B. Koribalski/CSIRO)

This multiwavelength image of the Cloverleaf ORC (odd radio circle) combines visible light observations from the DESI ( Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument) Legacy Survey in white and yellow, X-rays from XMM-Newton in blue, and radio from ASKAP (the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder) in red. (X. Zhang and M. Kluge/MPE/B. Koribalski/CSIRO)"This is the first time anyone has seen X-ray emission associated with an ORC," said Bulbul. "It was the missing key to unlock the secret of the Cloverleaf's formation."

X-rays of the Cloverleaf show gas that has been heated and excited by some process. In this case, the X-ray emissions reveal two groups of galaxies (totaling about a dozen galaxies altogether) that have begun to merge inside the Cloverleaf, heating the gas to 15 million degrees Fahrenheit.

The chaotic galaxy mergers are interesting, but they can't explain the Cloverleaf by themselves. Galaxies mergers happen all over the universe, while ORCs are a rare phenomenon. There's something unique going on to create something like the Cloverleaf.

"Mergers make up the backbone of structure formation, but there's something special in this system that rockets the radio emission," Bulbul said. "We can't tell right now what it is, so we need more and deeper data from both radio and X-ray telescopes."

That doesn't mean astronomers don't have any guesses.

"One fascinating idea for the powerful radio signal is that the resident supermassive black holes went through episodes of extreme activity in the past, and relic electrons from that ancient activity were reaccelerated by this merging event," said Kim Weaver, NASA project scientist for XMM-Newton.

In other words, ORCs like the Cloverleaf might require a two-part origin story – powerful emissions from active supermassive black holes, followed by galaxy merger shockwaves that give those emissions a second kick.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.

7 months ago

59

7 months ago

59