ARTICLE AD

Considering COVID-19 hasn't gone away, and we want to be as prepared as possible for the next potential pandemic, a new study into the most effective type of face mask offers some important insights: and there is a clear winner.

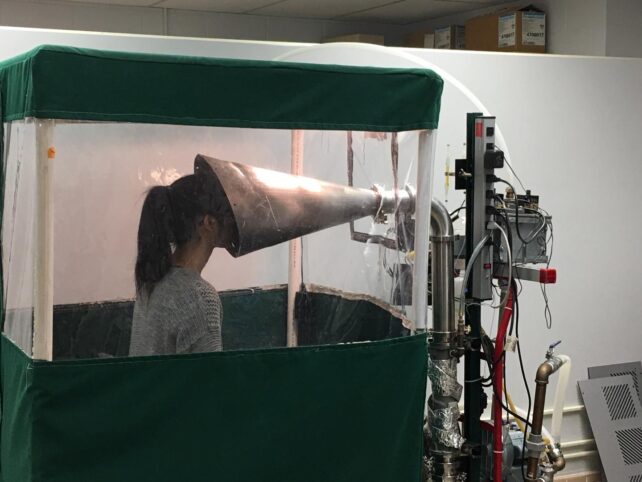

A team led by researchers at the University of Maryland in the US asked 44 volunteers with COVID-19 to breathe into a bespoke device called the Gesundheit II Machine, which can measure the number of virus particles in exhaled breath.

Four different mask types were tested this way, and the participants were told to vary their vocalizations while wearing the masks – one of the tests involved singing "Happy Birthday", for example. Each volunteer completed a 30-minute breathing session with a mask on, and another 30-minute session with no mask as a control.

The Gesundheit II Machine in action. (University of Maryland)

The Gesundheit II Machine in action. (University of Maryland)Of the four types of masks tested, the duckbill N95 mask came out on top: it blocked 99 percent of large particles and 98 percent of small particles from getting out into the air. Overall, 98 percent of the viral load was blocked by the N95.

"The research shows that any mask is much better than no mask, and an N95 is significantly better than the other options," says Donald Milton, an environmental health scientist and clinician at the University of Maryland.

"That's the number one message."

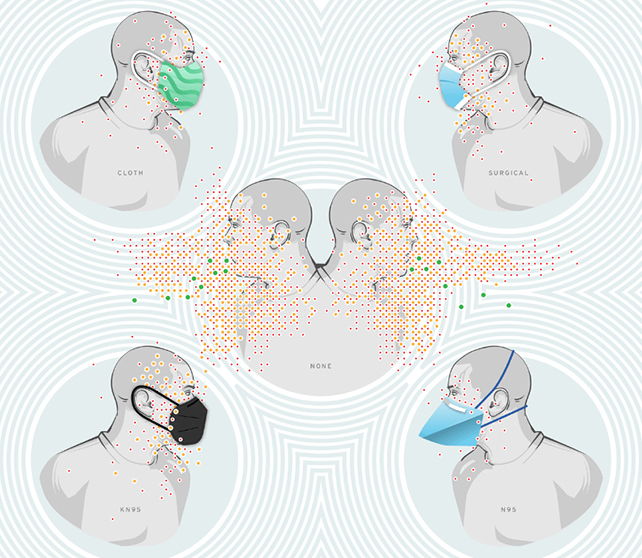

Four different types of mask were tested. (University of Maryland)

Four different types of mask were tested. (University of Maryland)The researchers also tested a cloth mask (blocking 87 percent of viral load), a surgical mask (74 percent), and a KN95 mask (71 percent). Clearly wearing any mask is a lot better than nothing – but there are also significant differences between masks.

While it's somewhat surprising for the widely recommended KN95 mask type to finish last, the team behind the study suggests that the amount of breath allowed to escape around the sides of the mask contributes to the lower score.

However, the N95 mask type scores highly across the board: according to the researchers, the power of the filter in the mask, the tight seal formed around the edges against the skin, and the extra space for breath to move inside the mask all contribute to its success.

"Data from our study suggests that a mildly symptomatic person with COVID-19 who is not wearing a mask exhales a little over two infectious doses per hour," says epidemiologist Jianyu Lai, from the University of Maryland. "But when wearing an N95 mask, the risk goes down exponentially."

This particular study didn't look at virus particles going in the other direction: in other words, how much protection the masks would offer to a wearer against virus particles that might be currently circulating in the air.

The types of masks included in the study were also limited, and the authors say they "should not be considered representative of all N95, KN95 respirators, and surgical masks."

In addition to vaccinations, masks play a vital role in limiting the spread of respiratory pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, responsible for COVID-19 – and the more data we can gather about different mask types, the better.

"Duckbill N95 masks should be the standard of care in high-risk situations, such as nursing homes and health care settings," says Lai.

"Now, when the next outbreak of a severe respiratory virus occurs, we know exactly how to help control the spread, with this simple and inexpensive solution."

The research has been published in eBioMedicine.

5 months ago

23

5 months ago

23