ARTICLE AD

The 'Last Ice Area' is expected to be the final place in the Arctic where ice persists all year round even as our planet warms up – but a new study suggests the region, and the ecosystem that relies on it, are going to disappear sooner than previously estimated.

Researchers led by a team from McGill University in Canada took a closer look at the Last Ice Area (LIA) using the Community Earth System Model, which goes into more detail than simulations used in the past.

In particular, the new model is more comprehensive in accounting for sea currents and ice flow, which in turn accelerates how quickly the last ice area becomes seasonally ice-free after the central Arctic Ocean does.

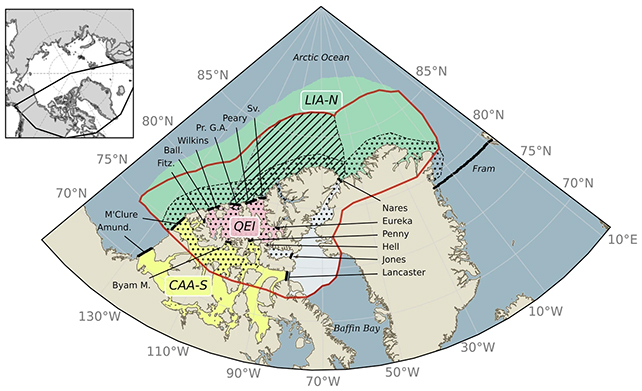

The designated Last Ice Area. (Fol et al., Communications Earth & Environment, 2025)

The designated Last Ice Area. (Fol et al., Communications Earth & Environment, 2025)"Our findings were based on high-resolution models, which consider sea ice transport through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago," says atmospheric scientist Bruno Tremblay, from McGill University.

"These suggest the LIA may vanish much sooner than previously thought."

Based on the team's calculations, the central Arctic Ocean could become seasonally ice-free every year as early as 2035, with the last remaining permanent ice disappearing about 6-24 years after the seasonal pattern is established.

They expect the Last Ice Area will be a region surrounding the Queen Elizabeth Islands north of Greenland and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

Earlier estimates suggested that the last remnants of permanent sea ice could hold out for several decades after seasonal ice-free periods were common. The new predictions bring that timetable forward significantly.

As always with these models, there are many variables: it's not certain how quickly the planet will warm up, exactly how permanent ice cover will influence seasonal ice cover, or how heat might be transported around the Arctic region.

However, the team did identify the north of the LIA as a crucial gatekeeper to the rest of the region, blocking ice flow away from the region and likely to be one of the last places where ice from multiple winters would be stacked up together.

"The fate of the LIA as a whole depends chiefly on sea ice conditions in its northern part, which hinders sea ice transport and allows replenishment of thick sea ice in the Queen Elizabeth Islands," write the researchers in their published paper.

Many species rely on year-round ice cover, including polar bears and seals (around a quarter of the world's polar bears live in or near the LIA).

This sea ice loss is already having consequences on wildlife, as portrayed by an episode of Our Planet in 2019, with walruses plummeting to death attempting to scale cliffs on land instead of their now-missing ice sheets. These once-abundant animals are now contenders for an endangered listing.

It's also used by indigenous peoples for subsistence hunting.

So important is the LIA that part of it has been designated as the Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area (MPA) by the Canadian government ("tuvaijuittuq" means "the place where the ice never melts" in Inuktut).

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

Now, the area is clearly in dire peril – another warning among many about the dangers of inaction on climate change.

"These findings underscore the urgency of reducing warming to ensure stable projections for the Last Ice Area and for critical Arctic habitats," says atmospheric scientist Madeleine Fol, from McGill University.

The research has been published in Communications Earth & Environment.

3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1