ARTICLE AD

There are jets in Jupiter’s magnetosheath, according to Voyager 2 mission data from 1979. The 45-year-old information is now revealing the dynamics of the plasma stream.

What Is Planet Nine and Why Can’t We Find It?

You may remember Voyager 2. It launched in August 1977 and is now 12.66 billion miles from Earth, hurtling out into interstellar space. It is the second-most-distant object humans have sent into space, after Voyager 1, which is over 15 billion miles away.

In 1979, Voyager 2 made a flyby of Jupiter, passing through the subsolar magnetosheath—the layer of the planet’s magnetosphere that is situated under the Sun. The spacecraft collected data during the transit which a team of scientists has now reviewed, revealing at least three jets above the gas giant. The team’s research was published this week in Nature Communications.

“Up until now, jets were discovered, with solid evidence, in the magnetosheath of Earth, Mars, and Jupiter,” wrote Chao Shen and Yufei Zhou, heliophysicists at China’s Harbin Institute of Technology and co-authors of the paper, in an email to Gizmodo. “Weak evidence of jets at Saturn (also part of this study) and Mercury were also reported.”

Now, the jets on Jupiter appear to be a sure thing. Jets are rapid streams of material, or, as the researchers described them “transient enhancements in plasma dynamic pressure.” The researchers detected three of them in Jupiter’s magnetosheath, the outer layer of the magnetosphere that surrounds the planet. One of the shocks was moving sunward, while two were moving away from the Sun.

Late last year, a different team of scientists found evidence of a fast-moving jet in Jupiter’s midriff. But that jet was moving through Jupiter’s gassy interior; the newly reported jets are downstream of Jupiter’s bow shock—the Sun-facing region of the magnetosphere that slows the solar wind.

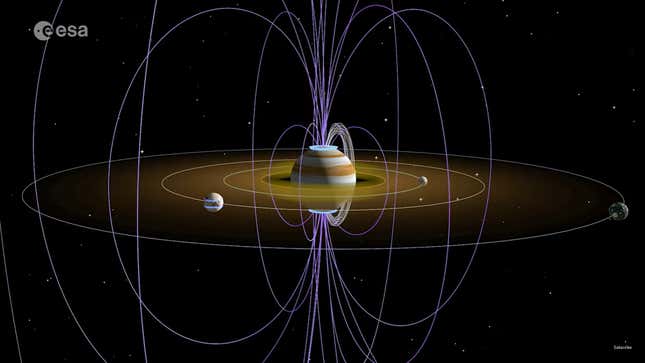

The Cassini spacecraft imaged Jupiter’s magnetosphere in 2002, revealing the charged particles that surround the planet. As NASA details in its release on the image, the magnetosphere is so large that if it was visible to the human eye, it would appear two to three times larger than the Moon to viewers on Earth. According to ESA, the planet’s magnetosphere is the largest structure in the solar system; it is about 15 times the size of the Sun.

Jupiter’s moons play a significant role in the magnetosphere’s dynamics, the researchers added. The plasma density in the magnetosphere causes it to “swell like a balloon,” they stated. “The moons whose orbits are close to the Jovian magnetopause and magnetosheath are likely to be directly affected by jets.”

Shen’s team found evidence of jets in Saturn’s magnetosheath in Cassini data; taken together with the evidence from Mercury and the confirmation of jets on Mars led them to conclude that jets may exist in all planetary magnetosheaths.

While the ongoing Juno mission could provide data on Jupiter’s magnetosheath, the data will be focused on the back end of the structure, the researchers added. In other words, it may not be able to collect data on the fast-moving jets that are just behind the bow shock. ESA’s JUICE mission—expected to arrive at Jupiter in 2031—could provide more insight into the planet’s magnetosheath, though its main target will be Jupiter’s icy moons.

More: Juno Spacecraft Gears Up for Closest Look at Jupiter’s Tormented Moon

1 year ago

99

1 year ago

99