ARTICLE AD

Ovulation is a crucial moment in the continuous thread of life, and yet we still know very little about it.

That's what motivated scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences to use mouse models to capture the entire phenomenon, start to finish, for the very first time.

In humans, ovulation occurs when an egg is released from a fluid-filled sac called a follicle, within the ovary. This egg then 'leaps' across to the fallopian tube, where it proceeds toward an eventual exit, either fertilized in the form of a baby, or unfertilized in menstrual discharge.

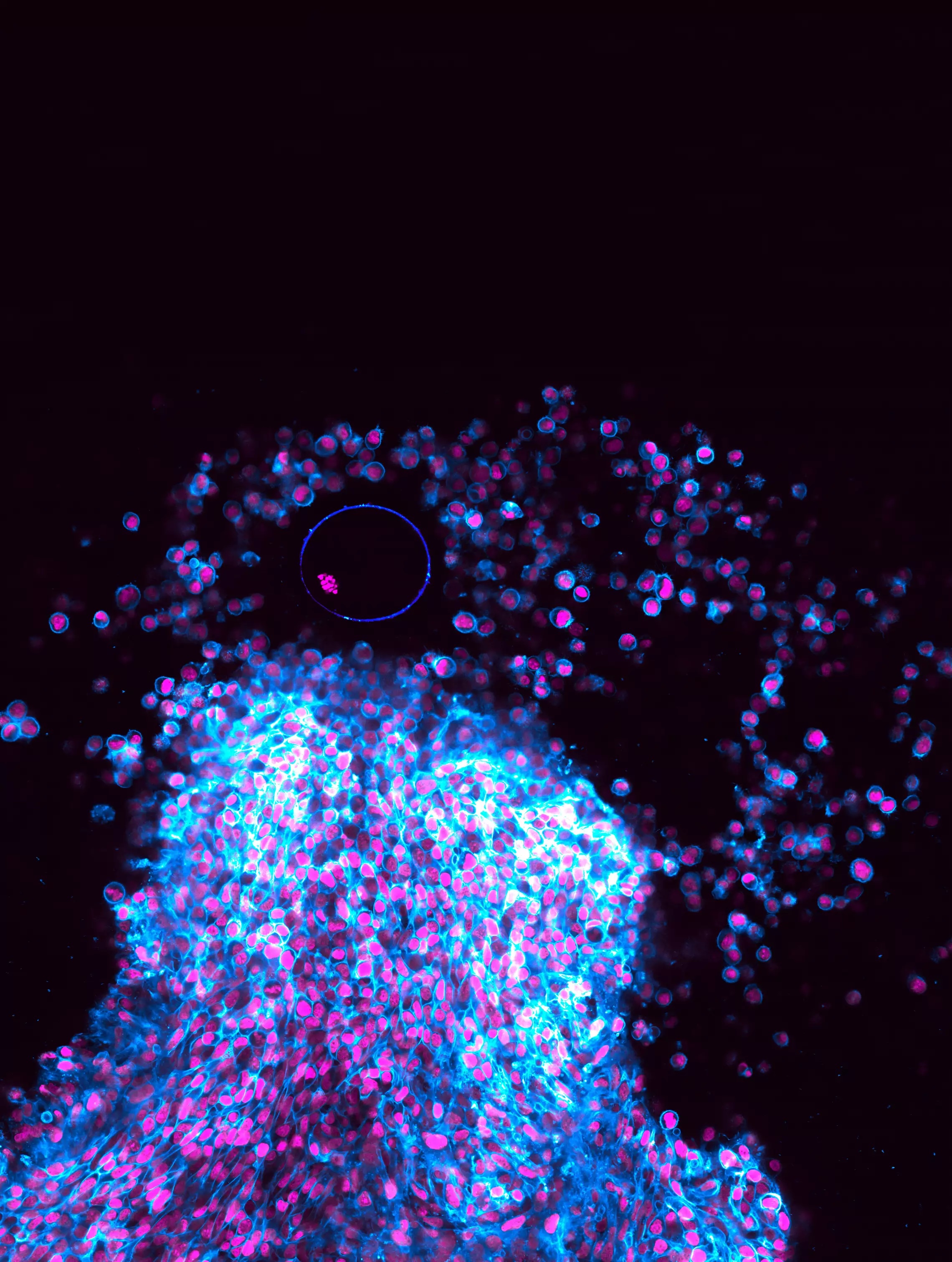

An egg that has just been ovulated next to the follicle. (© Christopher Thomas, Tabea Lilian Marx et al./ MPI f. Multidisciplinary Sciences)

An egg that has just been ovulated next to the follicle. (© Christopher Thomas, Tabea Lilian Marx et al./ MPI f. Multidisciplinary Sciences)Several follicles containing eggs develop each menstrual cycle, supported by specialist 'cumulus' cells that aid in each oocyte's development into a mature egg, or ovum.

But only one follicle – the largest and most well-developed – usually reaches ovulation, where the follicle ruptures like a party popper, releasing follicular fluid, cumulus cells, and, of course, the egg, to begin its journey to the uterus.

Using advanced microscopy, a team led by Max Planck biochemist Melina Schuh has visualized the entire ovulation process in the follicles of mice.

"Without a high-resolution imaging system, capturing the intricate and rapid dynamics of ovulation has not been possible," Schuh told ScienceAlert.

"Now, with our newly developed culture system compatible with advanced quantitative microscopy, we can observe the entire ovulation process in real time and in unprecedented detail."

Prying into one of the body's most intimate moments is no easy task. The follicles captured ovulating in these videos are transgenic mice follicles, and they're living ex vivo, meaning 'outside the body,' which isn't usually the best environment to get a follicle in the mood.

It took the team about a year of testing different custom-built imaging dishes and culture conditions to convince the petri-dish follicles to release their eggs under the microscope.

But it paid off, complete with live-action replays from different perspectives, where the various 'characters' of the process come into focus across a range of videos.

In this video, for instance, cell membranes are highlighted by a green fluorescent protein, while chromosomes are lit up in a magenta hue. We can see the single-celled egg clearly at the center of the left frame, and in the right frame, zoomed in, the egg's DNA wriggles around in meiosis, preparing for its breakout moment.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

In another video, green fluorescent protein has instead been used to track and reconstruct the surface of an oocyte in three dimensions, highlighting how it warps and gurgles, moving from the follicle center only one hour before surging through the rupture site in the final 10 to 20 minutes.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

This level of detail is a breakthrough for reproductive research, and it's easy to see in these videos just how many factors go into making an egg that's viable for fertilization.

"Now that we can visualize ovulation, we can start to uncover how it becomes impaired in conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), where ovulation doesn't occur normally," reproductive biologist Christopher Thomas told Science Alert.

"By understanding the precise ways in which ovulation is misregulated in such conditions, we may be able to help those affected achieve their goal of having children more easily," added medical researcher Tabea Lilian Marx.

The research was published in Nature Cell Biology.

4 hours ago

3

4 hours ago

3