ARTICLE AD

(Lhéritier et al., Science Advances, 2024)

(Lhéritier et al., Science Advances, 2024)

For 170 years, most of what we've known of the largest bug to ever live on Earth came from discarded headless casings with far too many legs.

Well-preserved fossils from France have now finally revealed the details of these surreal giants' heads, allowing an international team of researchers to locate this ancient creepy crawly's place in the tree of life.

"We discovered that it had the body of a millipede, but the head of a centipede," University Claude Bernard Lyon paleontologist Mickaël Lhéritier told Christina Larson at the Associated Press.

This suggests the giant bug, Arthropleura, which crawled across equatorial forests during the Carboniferous period up to 346 million years ago, belonged to a group of species that makes it like an ancestral cousin to today's millipedes and centipedes.

The team analyzed heads that belonged to two juvenile creatures who were only around 3 cm (1 inch) long. But oxygen levels in the Carboniferous were higher than today, allowing arthropods like dragonflies and sea scorpions to grow ginormous.

Arthropleura were no exception, with some species reaching up to 2.6 meters long (8.5 feet) – about the length of a small car – making them contenders for the largest bug known to have existed. Sea scorpions currently run a close second, with a length of up to 2.5 meters.

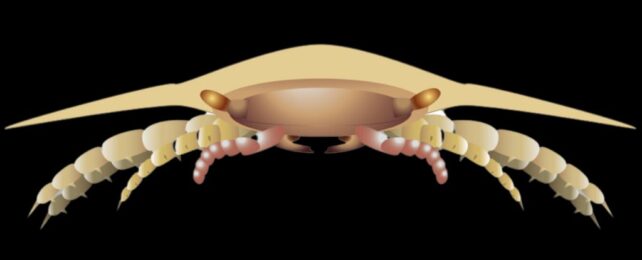

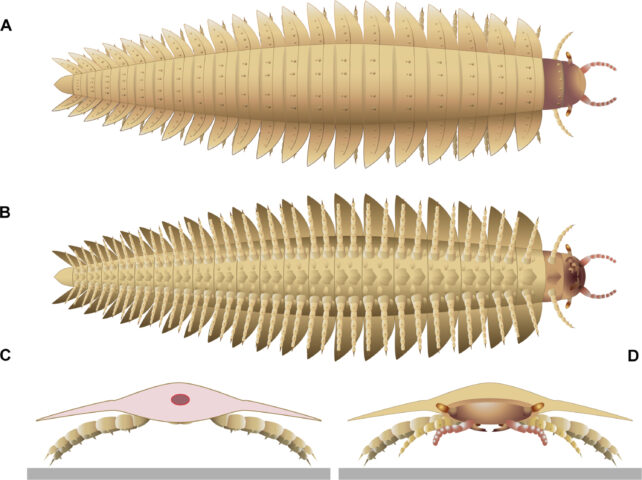

Diagram of Arthropleura. (Lhéritier et al., Science Advances, 2024)

Diagram of Arthropleura. (Lhéritier et al., Science Advances, 2024)Since the Carboniferous, oxygen levels have dropped from 35 percent of the atmosphere to today's 21 percent. This physiologically restricts the size of today's arthropods – the phylum including insects, spiders, and crabs – due to the lungless way they breathe.

Arthropleura left distinctive tracks and outgrown exoskeletons behind as they crawled across what's now North America and Europe. First discovered in 1854, there has been much confusion over their relationships with other species – it was even proposed they might be related to crustaceans.

But micro-CT scans of the well-preserved juveniles from Montceau-les-Mines have firmly solved the mystery – revealing hidden details still embedded in the rocks without damaging the specimens.

Like millipedes, Arthropleura have seven-segmented antennae, and mouthparts with a separated base plate and chewing lobe, though other features of their mouthparts are more like centipedes. But they lack the venomous pincers of centipedes and have stalked – possibly compound – eyes not found in the other two groups.

These findings support recent genetic evidence that millipedes and centipedes are closely related, and Arthropleura are related to the ancestor of both groups (Pectinopoda). Previous analysis of their physical features had grouped millipedes and centipedes separately.

"The stalked eyes found in Montceau specimens could point toward a semi-aquatic lifestyle," the team writes in their paper.

The now-known mouthparts of Arthropleura suggest that despite their intimidating appearance and size, these massive crawlers were harmless detritivores – recyclers of dead organic matter.

This research was published in Science Advances.

1 month ago

12

1 month ago

12