ARTICLE AD

Thiruvananthapuram, India – On a sweltering April afternoon, India’s junior Information Technology Minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar emerged from his air-conditioned SUV outside a prominent Hindu temple in Thiruvananthapuram, the capital of the southern Indian state of Kerala.

Wearing a traditional dhoti and a silk shawl draped over his shoulders, he stood reverently, his hands folded, before the idol of the Pazhavangadi Ganapathy Temple, the elephant-headed god who is believed to be the remover of obstacles, before proceeding to greet a crowd of about 500 people waiting for him.

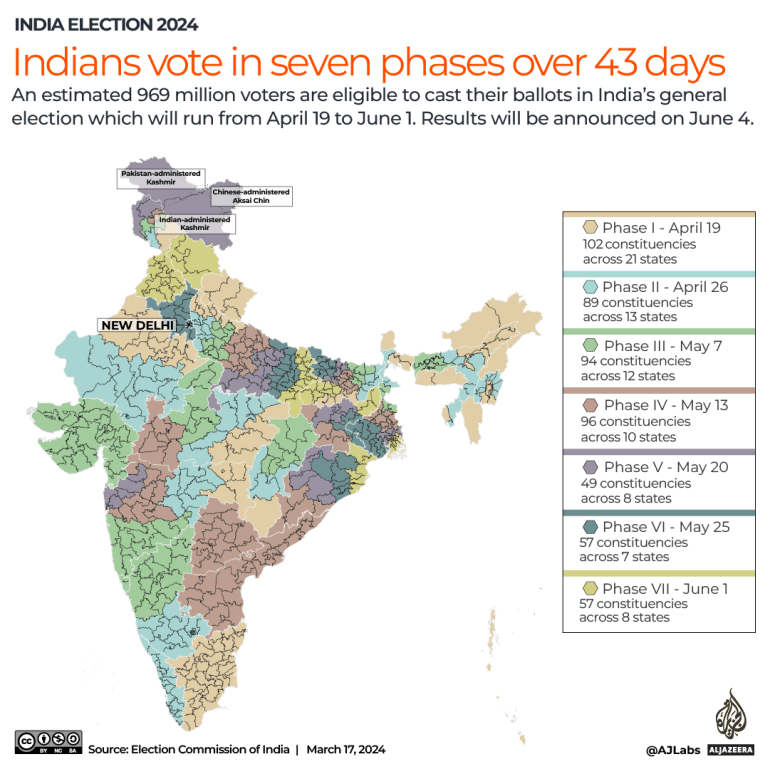

Chandrasekhar, an affluent entrepreneur-turned-politician, is contesting the Thiruvananthapuram parliamentary seat in India’s mammoth general election, which started on April 19. All the 20 constituencies in Kerala will vote on Friday, April 26 – the second phase of the seven-stage election.

Given Kerala’s political landscape and history, the 59-year-old candidate fielded by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) might need divine intervention to secure a win.

Chandrasekhar greets devotees at a Hindu temple in Thiruvananthapuram [TA Ameerudheen/Al Jazeera]

Chandrasekhar greets devotees at a Hindu temple in Thiruvananthapuram [TA Ameerudheen/Al Jazeera]

‘Double-digit seats’

Kerala is the only one of India’s major states where the BJP has never won a national seat, though it has seen a steady rise in its voter support, from 1.75 percent in 1984 to 13 percent in 2019.

During an election rally in February, Modi set higher ambitions for the party. “In the 2019 Lok Sabha [lower house of parliament] election, Kerala gave a two-digit vote share to the BJP. This time, the party would win double-digit seats from Kerala,” he said.

There is little evidence to suggest such broad support for the BJP in a state dominated by two coalitions for decades – the United Democratic Front (UDF), headed by the Congress Party, and the communist-led Left Democratic Front (LDF). In 2019, the UDF won 19 of 20 seats, with the LDF winning one. In 2014, the UDF bagged 12, while the remaining eight went to the LDF. In the state, the LDF is currently in power.

Though the UDF and the LDF have been exchanging heated barbs during the current campaign, and are contesting each other in Kerala, they are nationally both members of the Indian National Development Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), the opposition bloc that aims to stop Modi from winning a third straight term. In Kerala, opinion polls indicate the BJP could face a wipeout, with anti-BJP parties winning all of its 20 seats.

But the BJP is betting on Chandrasekhar and Thiruvananthapuram to defy those odds and break new ground in Kerala – for long a state that has set a benchmark for development indices including literacy in India.

For the past two national elections, the BJP has come second in Thiruvananthapuram, garnering more than 30 percent of the vote share, behind only the Congress, which leads the national INDIA alliance.

Chandrasekhar’s chief opponent is incumbent Shashi Tharoor of Congress. A former Undersecretary General at the United Nations and a widely regarded author, Tharoor, 68, is seeking re-election from the constituency for a fourth consecutive term.

Then there is Panniyan Raveendran of the Communist Party of India, a consistent political force in Thiruvananthapuram, where the party has won four times and finished second on six other occasions in the past 13 elections since 1977. Raveendran had won the seat in 2005.

‘I stand by Modi’

Decorated with dazzling lights and powerful speakers, Chandrasekhar’s convoy is impossible to ignore as it moves around the constituency. In contrast, spending by Tharoor and Raveendran appears to be muted.

Supporters lift Congress candidate Shashi Tharoor during a road show in Thiruvananthapuram [TA Ameerudheen/Al Jazeera]

Supporters lift Congress candidate Shashi Tharoor during a road show in Thiruvananthapuram [TA Ameerudheen/Al Jazeera]

Chandrasekhar is a millionaire businessman who built his fortune through ventures in Bengaluru, India’s information technology hub and the capital of the neighbouring state of Karnataka. He is the founder of Jupiter Capital, an equity and debt investment firm.

As of 2023, Jupiter Capital owned the majority stake in 51 companies spanning media, technology, aerospace, infrastructure, entertainment and hospitality sectors and minority shares in three others. Five of those companies are based in the tax havens of Mauritius and Luxembourg, according to Jupiter Capital’s filings with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

However, Chandrasekhar’s wealth has come under new scrutiny after the Congress questioned his election affidavit that said he had a taxable income of just 680 rupees ($8). The BJP minister clarified that his business suffered losses during the COVID-19 pandemic but his opponents have accused him of concealing his real income. India’s Election Commission has ordered the tax authorities to investigate the matter after the Congress lodged a formal complaint.

Chandrasekhar turned down a request for an interview from Al Jazeera.

Controversy aside, Chandrasekhar’s campaign seems to be striking a chord, at least among some in the Hindu community, which forms 62 percent of the electorate in Thiruvananthapuram, with Christians and Muslims forming 28 percent and 10 percent respectively.

Ramadas Rajendran, a 36-year-old medical representative, belongs to Kerala’s privileged Nair community. “I may not be affiliated with the BJP but I stand by Modi,” he told Al Jazeera at his home in the city’s middle-class Sreekaryam neighbourhood, expressing optimism about a BJP triumph.

“By nominating his minister for this constituency, Modi has assured us of having a representative committed to the area’s progress,” he added.

But a trip to predominantly Christian and Muslim fishing villages only a few kilometres west of Sreekaryam points to the challenges that Chandrashekhar and the BJP face.

“Tharoor is a captivating orator and effectively articulates our concerns in parliament. We need someone of his calibre to challenge Modi’s Hindutva [Hindu supremacist] agenda,” 50-year-old fisherman Rasheed Khan told Al Jazeera in the village of Beemapally.

In the neighbouring Poonthura fishing village with a large Christian community, a similar sentiment prevailed.

“We are determined to prevent Modi’s victory. He has remained silent as Christian churches were vandalised in Manipur by Hindu groups,” said 36-year-old Lawrence Bernard, referring to the northeastern state where ethnic violence – partly blamed on the BJP – has been going on for nearly a year.

“What will be our community’s fate if he [Modi] returns to power?” asked Bernard.

In fact, the Manipur violence is a major campaign issue in Kerala, with both the Congress and the communists attacking Modi and his BJP for failing to stop the killing of more than 260 people – most of them tribal Christians – and for the displacement of thousands of others.

Kerala’s ‘unique’ demography

Kerala’s distinctive demographic makeup is a key reason why the BJP’s increase in voting percentage has so far not translated into seats nationally.

Hindus constitute 55 percent of the state’s population, followed by Muslims at 27 percent and Christians at 18 percent. Together, the two minority groups make up nearly half – 45 percent – of the population, making them formidable forces in elections. The lack of trust among the minorities towards the BJP, which champions a Hindu majoritarian agenda, makes it difficult for the party to gain traction in Kerala.

“Though the BJP’s vote share has been increasing steadily, it cannot win even a single parliament seat because of demography,” K M Sajad Ibrahim, a professor of political science at Kerala University, told Al Jazeera.

The BJP has traditionally struggled to even win the Hindu vote in the state. In 2019, for instance, both the Nairs and the historically marginalised Ezhava – the largest Hindu group in the state – were split three ways between the UDF, the LDF and the BJP. Just 2 percent of the religious minorities voted for Modi’s party in the last election.

Chandrasekhar begins his campaign from a famous Hindu temple in Kerala [T A Ameerudheen/Al Jazeera]

Chandrasekhar begins his campaign from a famous Hindu temple in Kerala [T A Ameerudheen/Al Jazeera]

C P John, the leader of the Communist Marxist Party (CMP), a breakaway from the Communist Party of India, said one of the reasons for the BJP’s failure in Kerala is its “non-familiarity with the unique nature” of Kerala’s coalition politics, where even smaller parties have significant influence. Both the UDF and the LDF accommodate smaller parties, regardless of their size.

“However, the BJP’s failure to form alliances has made it a winless unit,” John told Al Jazeera.

Since 2015, the BJP has been in alliance with Bharath Dharma Jana Sena (BDJS), an outfit launched by Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam, a powerful Ezhava organisation.

“But the BDJS does not have the character of a proper political outfit. Though the BJP’s vote share increased because of the BDJS, a majority of Ezhava votes still go to either the UDF or the LDF,” said John.

‘BJP fails to comprehend Kerala’

The BJP has also used other strategies over the years to make a mark in the southern state.

One notable experiment occurred in 1991 when the BJP made a secret agreement with the Congress and the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) – a Muslim group – to contest against the LDF in one assembly seat and one parliamentary constituency, according to the memoirs of two former BJP state presidents, K G Marar and O Rajagopal.

Although both the BJP candidates lost, the party says the deal helped it gain acceptance as a mainstream political entity in Kerala.

The BJP’s critics say the party is now trying to foster discord between the Christians and the Muslims and disrupt the consolidation of anti-BJP votes among them. They accuse the BJP of pushing the idea of so-called “love jihad” – a conspiracy theory that alleges that Muslim men lure Hindu and Christian women into marriages and coerce them into converting to Islam.

A recent Bollywood film, Kerala Story, made similar claims – that numerous women from Kerala were forcibly converted to Islam and sent to fight for the ISIL (ISIS) group in the Middle East. The film was praised by Modi, while the BJP organised its showing across the country.

In the run-up to the election, some Catholic Churches in the state screened the film for their congregation and Sunday school students. The allegations made in the film have been widely debunked by local communities and independent experts.

C Sadanandan, a BJP leader in Kerala, defended the party’s focus on “love jihad”, saying that the Christians in Kerala are “aware of the repercussions of various forms of Islamic Jihad”.

“More Christians in Kerala are joining hands with the BJP to fight all forms of jihad. But the communists and the Congress are still supporting the jihadi elements,” he told Al Jazeera.

Predicting the BJP will win at least three constituencies in Kerala, he said: “In the past, the LDF and the UDF thwarted our winning chances by forming unholy alliances with the support of Islamic fundamentalists. It will change this time.”

Tharoor of the Congress, however, said that Kerala will not see the kind of religious fissures seen in other parts of India since the BJP came to power in 2014.

“The BJP fails to comprehend Kerala, its history and its people. Their politics, which demonises Muslims and Christians, may have found traction in northern India, but it will only backfire in the south, particularly in Kerala,” where Muslims and Christians have coexisted for more than a millennium, he said.

“Minorities are equal stakeholders in Kerala’s society, a fact the BJP fails to grasp.”

11 months ago

100

11 months ago

100