ARTICLE AD

An artist's impression of a spacecraft initiating a warp drive. (3000ad/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

An artist's impression of a spacecraft initiating a warp drive. (3000ad/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

One of the most significant barriers keeping humanity from the stars is the speed limit of the Universe.

Even if we had the technology to rocket us through space on high-speed colony ships, how fast we can travel normally is limited to light speed in a vacuum. Nothing in the Universe can move faster than 300,000 kilometers per second (186,000 miles per second) – and nothing with mass can reach that speed.

There are, however, theoretical workarounds and loopholes, which have to do with the fact that the very fabric of space-time itself can warp and bend. There's the notion of wormholes, or Einstein-Rosen bridges: shortcuts created by folding space-time.

And then there's the warp drive, or Alcubierre drive, a hypothetical engine that can create warps in space-time that circumvent the speed limit. It would work by squeezing space in the fore and expanding it aft, like toothpaste in a tube, thus shrinking the amount of space to be traveled and allowing some hypothetical craft to traverse the distance faster than if space-time had been left alone.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

For obvious reasons, this is not something humanity has been able to achieve. But an international group of scientists called Applied Physics has been theorizing about how it might work – and now they think they have a new solution, what they call the constant velocity warp drive.

"This study changes the conversation about warp drives," says physicist Jared Fuchs of Applied Physics, who did his PhD at the University of Alabama in Huntsville.

"By demonstrating a first-of-its-kind model, we've shown that warp drives might not be relegated to science fiction."

When Mexican theoretical physicist Miguel Alcubierre proposed his warp drive in 1994, it had a significant drawback. It required a bubble of negative energy density around an object to create the imbalance in space-time, powered by either exotic particles that we haven't yet discovered, or the mysterious dark energy that drives the expansion of the Universe.

This is not even remotely achievable, currently or maybe ever, but there's something else that can warp space-time – and that's gravity.

Previous work at Applied Physics described how developing a super-powerful gravitational field could squeeze space-time, whilst keeping the drive well within the bounds of known (if extremely difficult to pull off) physics.

The think tank's latest work focuses on a similar solution, theorizing a warp drive that can manipulate space-time to behave as though reacting gravitationally to normal matter.

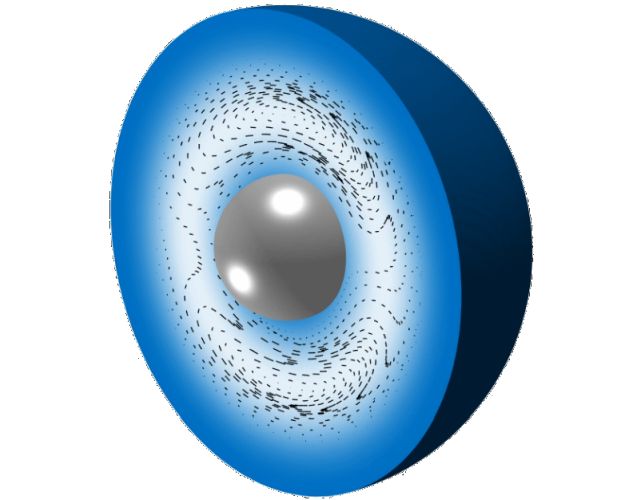

It consists of a stable shell of matter with, as the researchers describe, a "modified shift vector on its interior". The resulting warp 'bubble', pictured below, would send a spacecraft through space at speeds lower than that of light, but it could, the researchers say, work without needing exotic energy sources.

An illustration of the warp drive concept. (Applied Physics)

An illustration of the warp drive concept. (Applied Physics)"In this paper, we have developed the first constant velocity subluminal physical warp drive solution to date that is fully consistent with the geodesic transport properties of the Alcubierre metric," Fuchs and colleagues write in their published paper.

"This exciting new result offers an important first step toward understanding what makes physical warp solutions."

It's still not practical, mind you. But it could be a step in the right direction. The team intends to explore their model further to see if they can refine it, and plans to investigate ways to increase the velocities it can reach.

"Although such a design would still require a considerable amount of energy, it demonstrates that warp effects can be achieved without exotic forms of matter," says physicist Christopher Helmerich of Applied Physics and graduate student of the University of Alabama in Huntsville.

"These findings pave the way for future reductions in warp drive energy requirements."

The team's paper has been published in Classical and Quantum Gravity.

8 months ago

45

8 months ago

45