ARTICLE AD

Humans have an incredible ability to guess a person's name simply based on the appearance of their face.

A new study has found it could be a case of self-fulfilling prophecy.

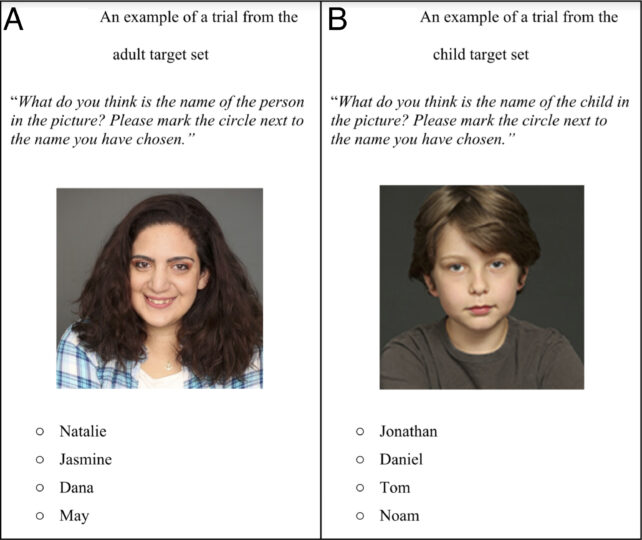

When a photograph of an adult was shown to participants with four possible name choices, they choose the correct name at a rate well above chance. When child faces were shown, however, the study's participants weren't nearly as good at matching faces to names.

The findings suggest that we tend to alter our appearance as we mature to better suit our own names, whether it be through hairstyles, makeup, glasses, piercings, or even facial expressions.

"We have demonstrated that social constructs, or structuring, do exist – something that until now has been almost impossible to test empirically," explains Yonat Zwebner, a marketing expert from the Reichman University in Israel.

"Social structuring is so strong that it can affect a person's appearance. These findings may imply the extent to which other personal factors that are even more significant than names, such as gender or ethnicity, may shape who people grow up to be."

In the past, studies have found evidence that a person's facial appearance is suggestive of their given name. But it wasn't clear if that was because people were given names to match their innate facial features as babies, or if their appearance developed over time to better suit their birth name.

The current study tests this nature or nurture debate using human participants and machine learning algorithms. It was conducted by researchers at the Reichmann University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

In one test, children between the ages of 8 and 12 and adults over the age of 18 were asked to match the faces and names of children and adults in a multiple-choice test.

Example of the study trial. (A) An example of an adult with possible names. (B) An example of a child with possible names (right). (Zwebner, PNAS, 2024)

Example of the study trial. (A) An example of an adult with possible names. (B) An example of a child with possible names (right). (Zwebner, PNAS, 2024)Both young and old participants were equally as good at matching adult faces to their corresponding names, but they could not do the same for the photographs of children aged 9 or 10.

Even when these young faces were digitally aged to look like adults, participants could not guess their names above the level of chance, which suggests a person's facial appearance changes after childhood to better suit their name over time.

In a follow-up test, machine learning algorithms were trained to process a larger collection of facial image data. As with humans who matched names with faces, the algorithm also found that adults with the same name tend to look more similar to each other than adults with different names.

But the same was not true of children with the same names.

"Together, these findings suggest that even our facial appearance can be influenced by a social factor such as our name, confirming the potent impact of social expectations," write Zwebner and colleagues.

Essentially, the team concludes, given names at birth are 'social tags' that can affect a person's appearance through a self-fulfilling prophecy.

As the years go by, researchers explain, people may internalize the characteristics and expectations associated with their name, embracing them "consciously or unconsciously, in their identity and choices."

In other words, how we 'should' look according to society's expectations seems to impact how adults do look.

When George Orwell famously wrote, "At 50, everyone has the face he deserves", he may have been on to something.

The participants guessing names, as well as the faces and names being guessed, were Hebrew-speaking Israelis, while the machine learning study was based on US databases of white caucasians – so it's unclear whether these findings apply beyond these cultural and ethnic groups.

Researchers now want to know at what age a person begins to exhibit the stereotypes associated with their names.

"These results suggest that people develop according to the stereotype bestowed on them at birth," the researchers conclude.

"We are social creatures who are affected by nurture: One of our most unique and individual physical components, our facial appearance, can be shaped by a social factor, our name."

The study was published in PNAS.

3 months ago

32

3 months ago

32