ARTICLE AD

A team of scientists is trying to understand how the trees of the Bobiri forest reserve in southern Ghana react to extreme heat.

Using thermal cameras, they are revealing the maximum temperatures different species experience, and how this affects their health and the functioning of the forest more broadly.

The resulting images are sent almost immediately to British and Ghanaian researchers at Plymouth University in the UK for analysis.

The team hope their work will influence which species Ghana chooses as part of its tree-planting drive, and build up the capacity of scientists locally. They would like to expand their research into other parts of Ghana and beyond.

They also hope their research will contribute to international collection and analysis of data related to tree growth, respiration and health.

The importance of forests

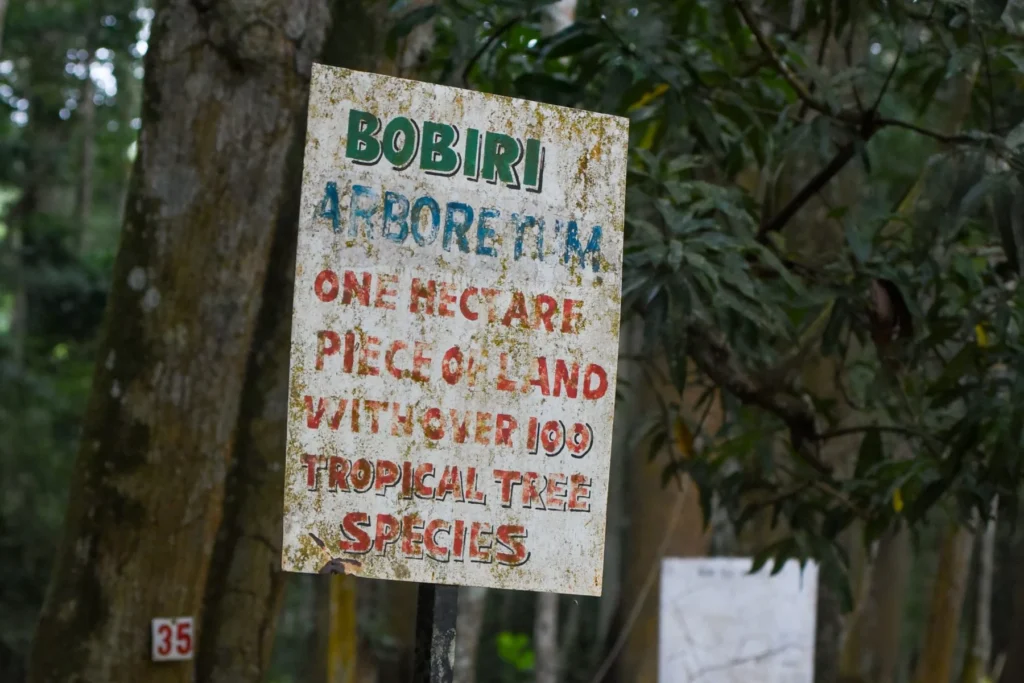

The Bobiri Forest is a diverse tropical ecosystem of 55 sq km that is home to native tree species including African mahogany, ofram, emire, black hyedua, afrormosia, oprono, baku and wawa. Some 400 species of butterfly and moth can also be found in the ecosystem, which has distinctive dry and wet seasons.

On a 0.2-hectare patch of the forest rises a metal tower overlooking the tallest visible tree. Located on a former loading bay for logged timber, the tower hosts both a thermal and a conventional camera, as well as a weather station. The remote-controlled cameras capture images of the canopy every 10 minutes. A solar panel at the tower’s base powers the operation.

Forests are important the world over. They cover roughly a third of Earth’s land, are home to over 80% of terrestrial species and absorb large amounts of CO2. Supporting this latter function will be essential if we are to limit global warming to 1.5C, states the UN Environment Programme. Ending deforestation, improving forest management, and reforestation are key.

Shalom Addo-Danso is a senior scientist at Ghana’s Forest Research Institute, which is co-leading on the Bobiri research. He tells Dialogue Earth that the project seeks to “better understand the impact of climate change on tropical forest canopy temperatures”.

The data collected, when combined with other similar studies, is helping to establish how rising temperatures are affecting the growth and respiration of particular tree species.

Leaf temperatures

Leaf temperatures matter primarily because they affect the ability of a plant to photosynthesise. Warm leaves can photosynthesise more efficiently than cold leaves, but once the temperature rises past a certain threshold, photosynthesis rates fall.

Most Earth system models assume that leaves are the same temperature as the air. But that is not necessarily the case, says William Hagan Brown, a Ghanaian Plymouth University PhD student involved in this research.

Analysing the Bobiri data, Brown has found that the leaves of both canopy-level and “emergent” trees (those breaking above the canopy) are significantly warmer than the ambient temperature. The difference is particularly apparent with larger leaves.

This is likely because the leaves of emergent trees, like ofram, are more exposed to direct sunlight. Other leaf differences, such as the rates at which they take in gas and lose water through their stomata, may also contribute to the variation. The researchers are studying the relative roles of these differences.

The leaf temperatures of evergreen species can sometimes reach as high as 40C, exceeding the threshold identified by ecologists for photosynthesis in plants. “When that happens, forests may cease to function as carbon sinks,” warns Brown.

Policy implications

Many studies indicate tropical forests face significant risks, particularly to their diversity, from extreme temperatures and droughts. Developing policy based on data collected from Ghana’s forests could help mitigate these impacts.

“Most of our policies are based on global values from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which are default values. Country-specific data will be informative,” says Addo-Danso. “Understanding how specific species in the country’s tropical forest – that are of conservation and economic concern – can tolerate extreme weather events is important.” Developing this understanding will be crucial to Ghana’s reforestation efforts as the world warms.

Ghana has been both losing and planting trees. Between 2000 and 2020, the country experienced a net tree-cover loss of 5,730 sq km, according to Global Forest Watch. Between 2002 and 2023, 1,430 sq km of primary forest, which contains native species that are vital to biodiversity, were destroyed – a 13% decline.

In 2016, the government pledged to restore two million hectares of forest cover by 2030. Implementation began the following year, via the Ghana Forest Plantation Strategy.

Some 6,280 sq km of degraded land had been put “under restoration” by the end of 2022, according to a report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature based on government data.

However, reforestation under the plantation strategy has its problems. Conservationists raised concerns to Dialogue Earth in 2023 that there was too great a focus on planting non-native, hardwood trees at the expense of native biodiversity.

Addo-Danso is optimistic that his work with Sophie Fauset, an associate professor of terrestrial ecology at Plymouth University, will reset some policies moving forward.

A separate study is exploring the productivity of the forest, including how the trees respire. “Ultimately, the findings can influence the country’s restoration efforts, because if your forest respires more than it absorbs, then there is a problem,” explains Addo-Danso. “In time, we can link the data from the various research sites and feed it into policy.”

African science, global collaboration

A network of researchers led by Fauset is studying leaf temperatures in Brazil, China, Ghana, India, the US and the UK. Each will contribute to the overall data analysis.

“It is to ensure that we get more reliable data,” Fauset tells Dialogue Earth. “We can understand the global patterns only if we put all the different types of forests together.”

Samuel Gyekyi is being trained as part of the project’s capacity-building strand. He studied natural resources management at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in the city of Kumasi, 30km from the Bobiri reserve. “I never had any practical experience during my studies,” he says. “This project has connected me to scientists and [is] offering me a hands-on experience.”

Fauset says the team is currently working on fulfilling the obligation under its funding agreement to make their data accessible to scientists worldwide.

The scientists are hoping to extend their research into other parts of Ghana and the Congo Basin. The latter would make for a useful comparison to Ghana because of its wetter climate, Fauset adds.

“This is a study I am proud of, because the infrastructure comes in handy for other research purposes, not only for scientists in Ghana, as there are many collaborative research [projects] ongoing in the Bobiri Forest that are targeted at air and leaf temperatures,” Addo-Danso concludes.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

14 hours ago

11

14 hours ago

11