ARTICLE AD

Postmortem brain samples collected last year contain considerably more microplastics than similar samples collected nearly a decade ago, a new study has found, indicating the tiny synthetic particles accumulate in our vital organs over time.

What's more, University of New Mexico health scientist Alexander Nihart and colleagues found greater concentrations of these problematic petrochemical leftovers in brain samples than in samples of kidneys and livers.

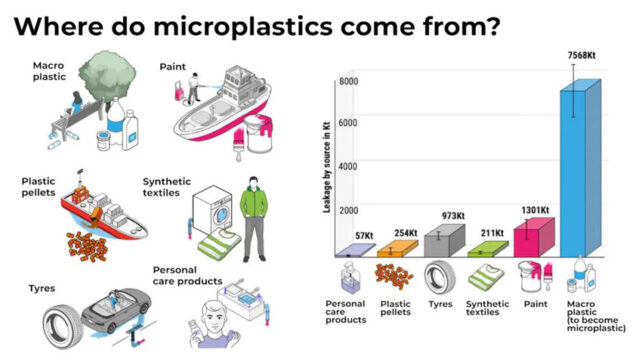

Between 1950 and 2019, some 9 billion metric tons of plastic have been churned out for use in items as diverse as single-use packaging, food containers, children's toys, garments, and lawn furniture.

Much of this material has since broken up into ever-smaller pieces, producing a fine dust that is carried far and wide around the globe. The resulting micro- and nanoparticles now contaminate every place we care to look, from archaeological remains to our own poop and the deepest ocean trenches.

"Environmental concentrations of anthropogenic microplastic and nanoplastic, polymer-based particulates ranging from 500 µm in diameter down to 1 nm, have increased exponentially over the past half century," Nihart and team write in their paper.

The long-term impacts and the potential for incremental effects of plastic particles embedded in our tissues remain unknown, though evidence suggests there might be cause for concern.

One study, yet to be published, has linked these tiny plastics in placenta to premature births. They've also been linked with blocked blood vessels in mouse brains. Another study found exposure to additives in commonly used plastics was associated with millions of deaths.

So Nihart and colleagues investigated tissues samples from 52 human bodies that underwent autopsies in 2016 and 2024. Every single sample they tested contained plastic particles.

(Raubenheimer, Chemistry International, 2025)

(Raubenheimer, Chemistry International, 2025)While samples from livers and kidneys had similar amounts of plastic, the researchers found the brain samples had up to 30 times higher concentrations.

This is surprising. The liver and kidneys help filter and break down waste in the body, potentially increasing their contact with circulating particles. Our brains also have extra protection against contaminants – the brain-blood barrier – which ought to prevent the passage of such material.

Nihart and team also compared their data to earlier brain samples from 1997-2013. They found a clear increasing trend over time, and suspect the exponential increase in environmental concentrations of micro- and nanoplastics is being mirrored within our bodies.

Plastic concentrations in the analyzed tissues were not influenced by age, ethnicity, or cause of death. But there were higher concentrations of plastic in the samples from people with dementia diagnoses than those without.

"Atrophy of brain tissue, impaired blood–brain barrier integrity, and poor clearance mechanisms are hallmarks of dementia and would be anticipated to increase micro- and nanoplastic concentrations," explain the researchers, so once again, we don't know for sure if accumulations of plastic material contributes to poor health.

Nihart and colleagues add to the chorus of researchers who have been urging for years now for more research into the health impacts of microplastics.

Meanwhile, we're all continuing to absorb fragments of plastic as their production continues to increase.

"Plastics are petrochemical products: substances which are ultimately derived from oil and gas," University of Exeter global development researcher Adam Hanieh, who was not involved in the study, reminds us in a recent article for The Conversation.

"It has been estimated that by 2040, plastics will account for as much as 95 percent of net growth in oil demand."

This research was published in Nature Medicine.

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2