ARTICLE AD

The reflexes controlling our ear movements never vanished. (Viktor Ketal/Getty Images)

The reflexes controlling our ear movements never vanished. (Viktor Ketal/Getty Images)

Tens of millions of years ago, our primate ancestors responded to noises in much the same way many other mammals do, pricking their ears and deftly turning them towards the sound's source.

While a few might achieve a weak wiggle or two, modern human ears have been virtually reduced to mere flesh ornaments, with all the dexterity of handles on a coffee mug.

It's not for lack of trying. Researchers from Saarland University in Germany, hearing-aid manufacturer WS Audiology, and the University of Missouri have shown the muscles once tasked with moving our outer ears – or auricles – still do their darndest to contract when we strive to hear something interesting.

"There are three large muscles that connect the auricle to the skull and scalp and are important for ear wiggling," says Saarland University neuroscientist Andreas Schröer.

"These muscles, particularly the superior auricular muscle, exhibit increased activity during effortful listening tasks. This suggests that these muscles are engaged not merely as a reflex but potentially as part of an attentional effort mechanism, especially in challenging auditory environments."

Schröer led a team of scientists in a quest to determine just how vestigial our ear's muscles really were after a study found their electromyographic (EMG) signals accurately predicted sound sources an individual was focusing on.

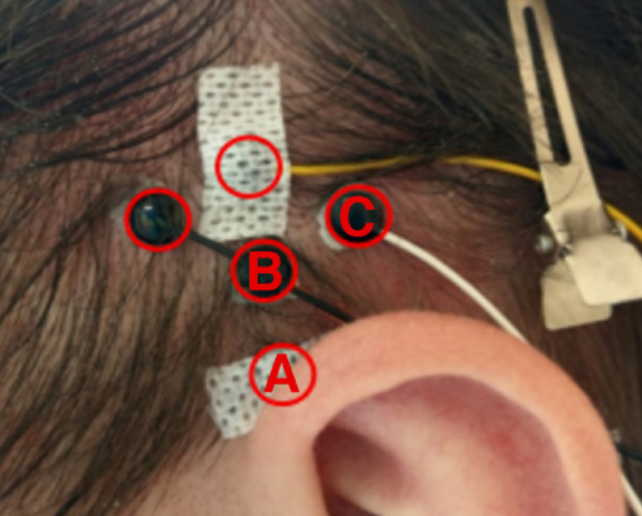

They recruited 20 native German speakers who had normal hearing and no known neurological or cognitive deficits. The participants, all young adults, had electrodes fitted to the sides of their heads to record their EMG signals as they listened to snippets of audiobooks while being distracted by a podcast playing simultaneously.

Angles of sound delivery and complexities of the distractions were also adjusted to create scenarios of varying difficulty.

Five EMG electrodes were placed on the volunteers' heads to record signals. (Schröer et al., Frontiers of Neuroscience, 2025)

Five EMG electrodes were placed on the volunteers' heads to record signals. (Schröer et al., Frontiers of Neuroscience, 2025)Participants were asked to rate how well they listened under the different conditions, answering questions on the audiobook topics to verify they were in fact paying attention. Meanwhile, electrical signals from the ear's left and right superior auricular and posterior auricular muscles, as well as the jaw's masseter muscles, were recorded and later processed for a statistical analysis.

Much as a dog might swivel their ears at the sound of the fridge door opening, signals indicated human posterior auricular muscles strained to pull the ears around to scoop up important sound signals behind them when the environment was full of clatter and noise.

Muscles supporting a dog's ears can direct its auricles to better intercept sounds. (Dex Ezekiel/Unsplash)

Muscles supporting a dog's ears can direct its auricles to better intercept sounds. (Dex Ezekiel/Unsplash)Whether the EMG signal translates into any significant contractions might depend largely on individuals. One study suggests only 10 to 20 percent of people can use the muscles attached to their auricles to briefly wiggle their ears.

It's believed our ancestors all but lost their ability to manipulate their cute, fuzzy little auricles around 25 million years ago when lesser apes and Old World monkeys parted ways, locking our ears in place and forcing us to turn our tiny primate heads to listen more attentively.

The findings suggest that while the muscles responsible for tugging our ears may have weakened, the neurological wiring is still there, reflexively sparking in vain as we try to pull meaningful sounds from the cacophony of modern life.

"The ear movements that could be generated by the signals we have recorded are so minuscule that there is probably no perceivable benefit," says Schröer.

"However, the auricle itself does contribute to our ability to localize sounds. So, our auriculomotor system probably tries its best after being vestigial for 25 million years, but does not achieve much."

Schröer hopes to test this assumption in the future, potentially expanding experiments to evaluate the influence of these vestigial twitches on people with hearing impairments.

This research was published in Frontiers in Neuroscience.

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2