ARTICLE AD

Getting a spacecraft to another star is a monumental challenge. However, that doesn't stop people from working on it.

The most visible groups currently doing so are Breakthrough Starshot and the Tau Zero Foundation, both of whom focus on a very particular type of propulsion-beamed power.

A paper from the Chairman of Tau Zero's board, Jeffrey Greason, and Gerrit Bruhaug, a physicist at Los Alamos National Laboratory who specializes in laser physics, takes a look at the physics of one such beaming technology – a relativistic electron beam – how it might be used to push a spacecraft to another star.

There are plenty of considerations when designing this type of mission. One of the biggest of them (literally) is how heavy the spacecraft is.

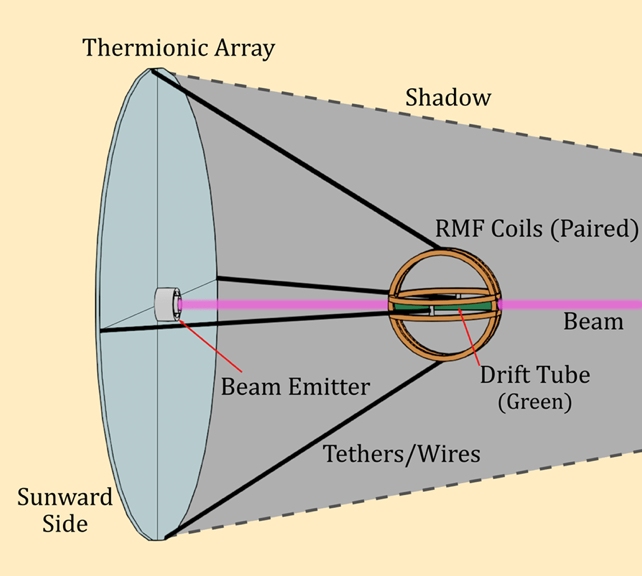

Depiction of the electron beam statite used in the study. (Greason & Bruhaug)

Depiction of the electron beam statite used in the study. (Greason & Bruhaug)Breakthrough Starshot focuses on a tiny design with gigantic solar "wings" that would allow them to ride a beam of light to Alpha Centauri. However, for practical purposes, a probe that small will be able to gather little to no actual information once it arrives there – it's more of a feat of engineering rather than an actual scientific mission.

The paper, on the other hand, looks at probe sizes up to about 1,000 kg – about the size of the Voyager probes built in the 1970s. Obviously, with more advanced technology, it would be possible to fit a lot more sensors and controls on them than what those systems had.

But pushing such a large probe with a beam requires another design consideration – what type of beam?

Breakthrough Starshot is planning a laser beam, probably in the visible spectrum, that will push directly on light sails attached to the probe. However, given the current state of optical technology, this beam could only push effectively on the probe for around 0.1 AU of its journey, which totals more than 277,000 AU to Alpha Centauri.

Even that minuscule amount of time might be enough to get a probe up to a respectable interstellar speed, but only if it's tiny and the laser beam doesn't fry it. At most, the laser would need to be turned on for only a short period of time to accelerate the probe to its cruising speed.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

However, the authors of the paper take a different approach. Instead of providing power for only a brief period of time, why not do so over a longer period? This would allow more force to build up and allow a much beefier probe to travel at a respectable percentage of the speed of light.

There are plenty of challenges with that kind of design as well. First would be beam spread – at distances more than 10 times the distance from the Sun to the Earth, how would such a beam be coherent enough to provide any meaningful power?

Most of the paper goes into detail about this, focusing on relativistic electron beams. This mission concept, known as Sunbeam, would use just such a beam.

Utilizing electrons traveling at such high speeds has a couple of advantages. First, it's relatively easy to speed electrons up to around the speed of light – at least compared to other particles. However, since they all share the same negative charge, they will likely repel each other, diminishing the beam's effective push.

That is not as much of an issue at relativistic speeds due to a phenomenon discovered in particle accelerators known as relativistic pinch. Essentially, due to the time dilation of traveling at relativistic speeds, there isn't enough relative time experienced by the electrons to start pushing each other apart to any meaningful degree.

Calculations in the paper show that such a beam could provide power out to 100 or even 1,000 AU, well past the point where any other known propulsion system would be able to have an impact. It also shows that, at the end of the beam powering period, a 1,000 kg probe could be moving as fast as 10% of the speed of light – allowing it to reach Alpha Centauri in a little over 40 years.

There are plenty of challenges to overcome for that to happen, though – one of which is how to get that much power formed into a beam in the first place. The farther a probe is from the beam's source, the more power is required to transmit the same force.

frameborder="0″ allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen>

Estimates range up to 19 gigaelectron volts for a probe out at 100 AU, a pretty high-energy beam, though well within our technology grasp, as the Large Hadron Collider can form beams with orders of magnitude more energy.

To capture that energy in space, the authors suggest using a tool that doesn't yet exist, but at least in theory could – a solar statite. This platform would sit above the Sun's surface, using a combination of force from the push of light from the star and a magnetic field that uses the magnetic particles the Sun emits to keep it from falling into the Sun's gravity well.

It would sit as close as the Parker Solar Probe's closest approach to the Sun, which means that, at least in theory, we can build materials to withstand that heat.

The beam forming itself would happen behind a massive sun shield, which would allow it to operate in a relatively cool, stable environment and also be able to stay on station for the days to weeks required to push the 1,000 kg probe out as far as it would go.

That is the reason for using a statute rather than an orbit – it could stay stationary relative to the probe and not have to worry about being occluded by the Earth or the Sun.

All this so far is still in the realm of science fiction, which is why the authors met in the first place – on the ToughSF Discord server, where sci-fi enthusiasts congregate.

But, at least in theory, it shows that it is possible to push a scientifically useful probe to Alpha Centauri within a human lifetime with minimal advances to existing technology.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.

1 day ago

18

1 day ago

18